As representatives of EFRI, which advocates for over 1,600 victims of cybercriminals who made authorised card payments and bank transfers after being socially engineered by scammers, we write from direct experience with the devastating human cost of APP fraud. Many of these individuals lost their entire life savings and now suffer from severe psychological trauma; some committed suicide, some died from cancer, dementia, or other sicknesses, for sure accelerated by the experienced trauma.

Despite banking relationships spanning decades, only a handful received any assistance from their Payment Service Providers when they sought help. The vast majority experienced complete institutional indifference – no support, no empathy, just blanket denial of any responsibility. Numerous victims changed banks after encountering this callous response from institutions they had trusted for years. Tellingly, not a single victim received reimbursement without threatening legal action, revealing the systemic nature of institutional resistance to accepting responsibility.

The European Banking Institute’s recent working paper by Emanuel van Praag, “Authorised Push Payment Fraud: Suggestions for the Draft Payment Services Regulation,” presents a nuanced analysis of APP fraud liability. However, we fundamentally disagree with the paper’s core recommendation to limit Payment Service Provider (PSP) liability primarily to cases involving bank impersonation fraud, while leaving other fraud scenarios to the discretion of Member States.

The Current Regulatory Landscape

Since PSD2, European law has implemented a liability shift from consumers to Payment Service Providers for unauthorised payments – transactions where criminals obtain payment credentials without the account holder’s knowledge or consent. This regulatory intervention proved remarkably successful, driving massive reductions in unauthorised fraud as banks invested heavily in security technologies and fraud detection systems.

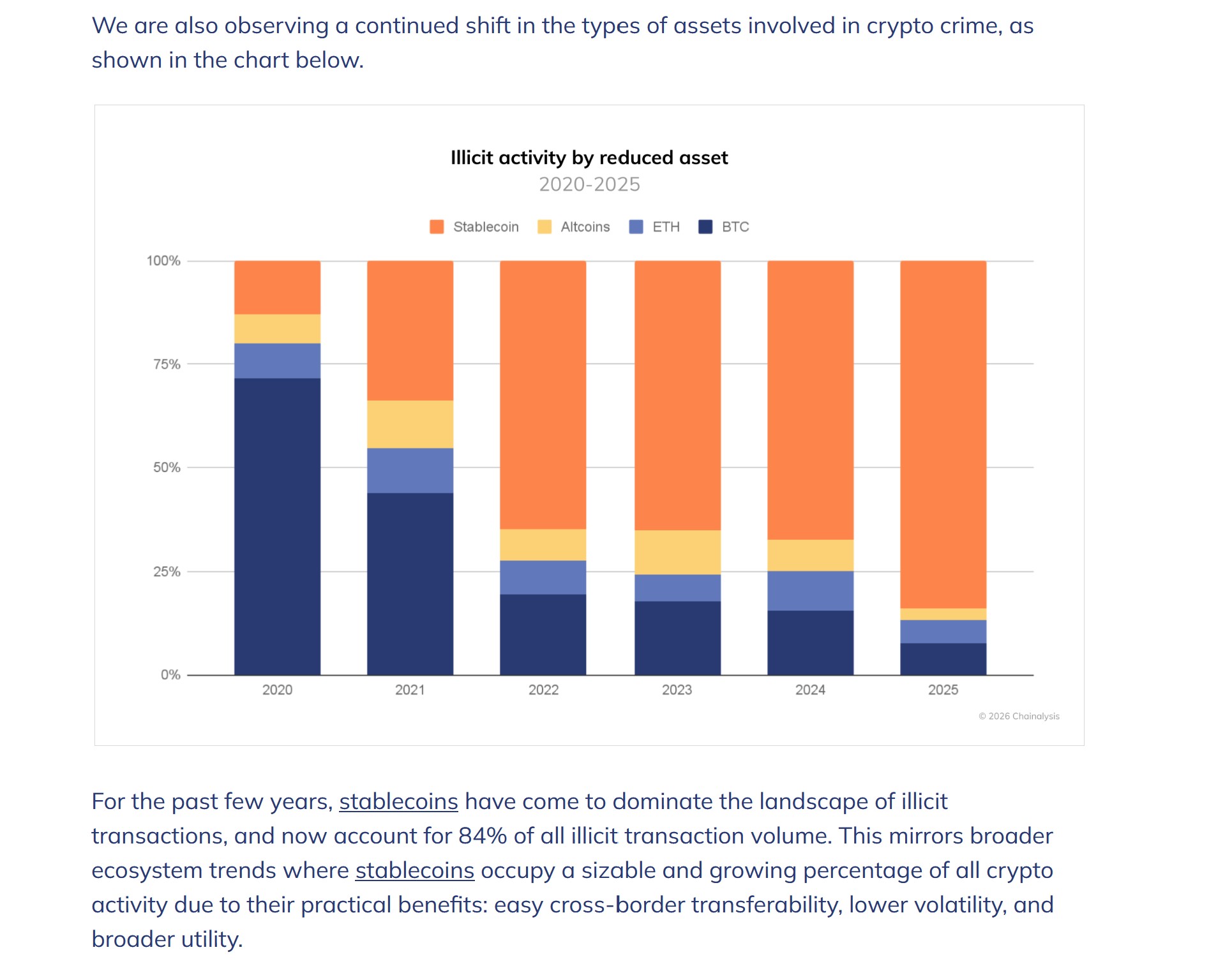

However, the global surge in cybercrime has seen criminals adapt by pivoting toward social engineering tactics designed to trick consumers into making authorised payments themselves. This evolution has led to a significant increase in Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud worldwide, with victims bearing the full financial loss. The scale of this problem now threatens public trust in digital payment systems, forcing legislators worldwide to consider extending liability shift principles to cover authorised fraud scenarios.

The European Proposal!

The European Commission’s original Payment Service Regulation (PSR) proposal suggested PSP liability specifically for bank impersonation fraud – where fraudsters pose as the victim’s bank to manipulate payment authorizations. The European Council has since proposed expanding this to cover broader fraud scenarios, including the different forms of social engineering. And of course this proposal resulted in a heated debate.

EBI's proposal

Van Praag’s paper, published as No. 190; in the EBI Working Paper Series argues for a middle ground: PSP liability should apply only to fraud that “abuses people’s trust in the payment system” (such as impersonation of banks, regulators, or police), while other fraud types should remain subject to national private law and Member State discretion as these kind of scams do not challenge the “trust in the payment systems”.

Why This Approach Falls Short!

1. Cross-Border Reality Demands Harmonized Solutions

The establishment of the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) — praised for enabling seamless digital payments across 36 jurisdictions and for driving Europe’s prosperity — also exposes a severe weakness: 95 % of the victims registered with EFRI made cross‑border transfers, because fraudsters exploit the very multi‑jurisdictional environment that SEPA creates. The fraudsters are well aware of the opportunities to profit from the non-harmonised law enforcement rules in Europe.

Under the proposal put forward by EBI (Emanuel van Praag), the position of victims of romance scams, investment fraud, invoice fraud and large‑scale authorised push‑payment (APP) scams would remain exactly as it is today. Advising victims to rely on national refund rules is, frankly, cynical.

Our day-to-day casework demonstrates the varying interpretations of banks’ duty-of-care obligations by courts across Europe. This fragmentation leaves consumers unevenly protected, and banks are well aware that scam victims are often reluctant to litigate against them for multiple practical and emotional reasons.

The new EU Collective Redress Directive may even exacerbate the situation, as it still fails to resolve the crucial conflict-of-laws question for cross-border class actions.

Digital Trust as an Economic Imperative

The EU has consistently positioned digitalisation as a key growth driver. The Digital Single Market Strategy, the Digital Decade targets, and the recent European Digital Identity Wallet initiative all depend on consumer confidence in digital financial services.

Consumers fundamentally trust banks to act as gatekeepers in the digital payment ecosystem. When this trust is exploited, regardless of whether the fraudster specifically impersonates the bank, the underlying confidence in digital payments erodes. Romance scams and investment fraud often succeed precisely because victims believe legitimate financial institutions would prevent such transfers if they were truly dangerous.

To assume that with WhatsApp fraud, invoice fraud, or romance fraud, there is no direct “association” with trust in the payment system is just nonsense.

Scammers willingly pay a premium for Deutsche Bank accounts because most European consumers would never suspect that the bank could facilitate fraud, even though, in 2018, it opened more than 100 accounts for professional money‑launderers for investment scams.

The Level Playing Field Promise

EU policymakers have repeatedly committed to ensuring that consumer protection in digital payment methods matches or exceeds that of traditional payment systems. The PSD2 framework itself was built on this principle to prevent unauthorised transactions.

If a criminal physically steals a payment card and PIN, the bank bears liability (subject to gross negligence exceptions). When the same criminal achieves the same result through social engineering—obtaining the same payment credentials through deception rather than theft—the victim currently bears the loss in most jurisdictions. This inconsistency undermines the EU’s level playing field commitment

Profit-Risk Alignment

Payment Service Providers have been the primary beneficiaries of payment digitalisation. Digital transactions are significantly cheaper to process than cash or check-based payments, while offering new revenue streams through data monetisation and premium services.

The “polluter pays” principle suggests that those who profit from creating new channels for fraud should bear responsibility for the associated risks. Banks actively promote digital payment adoption while simultaneously benefiting from reduced physical security costs (no more armored cars, fewer physical branches, reduced cash handling).

Regulatory Incentives Drive Results

The dramatic reduction in unauthorised payment fraud following the implementation of PSD1 and PSD2 demonstrates how liability allocation drives innovation in fraud prevention. When banks faced clear liability for card-not-present fraud, they invested heavily in 3D Secure protocols, machine learning fraud detection, and real-time transaction monitoring.

Limiting APP fraud liability to narrow categories removes these incentives for broader fraud scenarios, essentially telling banks they need not invest in detecting romance scams or fake investment opportunities. This creates perverse incentives where banks might even prefer that fraudsters use social engineering rather than technical attacks.

Resource Asymmetry and Information Advantages

Banks possess vastly superior resources for detecting and preventing fraud compared to individual consumers. Advanced AI systems, transaction pattern analysis, velocity checks, and real-time risk scoring are beyond the capabilities of any consumer.

Moreover, banks benefit from critical information asymmetries. They have access to aggregated fraud intelligence across their entire customer base and can identify emerging fraud patterns in real-time. When a new romance scam technique emerges, banks observe it across hundreds of victims while each consumer experiences it in isolation. Individual consumers cannot access this collective knowledge and must rely entirely on their own judgment when faced with sophisticated psychological manipulation.

Banks can also implement systemic solutions, such as cooling-off periods for large transfers, enhanced verification for new payees, behavioural biometrics, and cross-institutional fraud intelligence sharing—capabilities entirely beyond the reach of individual consumers.

The Authentication Paradox

The distinction between authorised and unauthorised fraud becomes increasingly meaningless as authentication technology advances. Strong Customer Authentication (SCA) requirements make traditional card fraud significantly more challenging, prompting criminals to shift toward social engineering approaches that exploit human psychology rather than technical vulnerabilities.

Penalising consumers for criminals adapting to improved security measures creates perverse incentives. The more effective banks become at preventing unauthorised fraud, the more liability shifts to consumers as criminals pivot to authorised fraud techniques.

Regulatory Arbitrage and the Race to the Bottom

Under van Praag’s approach, fraudsters would rationally gravitate toward jurisdictions with weaker consumer protection for non-bank impersonation fraud. This could create a “race to the bottom” in fraud prevention standards across EU Member States, thereby undermining the objective of the single market.

Criminal organizations are highly adaptive and will exploit regulatory gaps. If romance scams face stronger liability regimes in some countries but not others, fraud operations will simply relocate or target consumers in more permissive jurisdictions

Network Effects and Systemic Risk

APP fraud creates network effects that individual bank liability decisions cannot adequately address. Each successful fraud emboldens criminals and generates intelligence for future attacks. When one bank allows a romance scam to proceed unchecked, it potentially creates victims who become unwitting money mules for subsequent fraud

The systemic nature of fraud means individual bank decisions have spillover effects across the entire payment ecosystem. A bank that takes a lenient approach to fraud detection essentially externalises costs to other financial institutions and their customers.

Implementation and Enforcement Complexity

Van Praag’s framework would require regulators and courts to categorize fraud types and determine which scenarios “abuse trust in the payment system.” This creates expensive litigation over definitional boundaries rather than focusing resources on actual fraud prevention.

Financial institutions would spend significant resources on legal compliance and categorisation rather than fraud detection innovation. Regulatory uncertainty about which types of fraud qualify for PSP liability could actually discourage proactive fraud prevention measures.

Rather than creating artificial distinctions between fraud types, the PSR should establish comprehensive PSP liability for all APP fraud scenarios, subject to appropriate (and well-defined) gross negligence exceptions. This approach would:

- Harmonize protection across the EU, eliminating regulatory arbitrage

- Maintain digital payment trust essential for economic digitalisation

- Incentivise innovation in fraud prevention across all scenarios

- Ensure fair risk allocation between institutions and consumers

- Leverage superior resources where they can be most effective

The gross negligence standard can and should be applied differently in various scenarios as appropriate. A consumer who ignores multiple bank warnings about a suspicious transfer might face different treatment than one who receives no warnings about a sophisticated romance scam.

The EU Must Ensure Unwavering Trust in Payment System

Van Praag’s paper provides a valuable analysis of the complex legal and policy issues surrounding APP fraud. However, its recommendation for limited PSP liability fails to address the cross-border nature of modern fraud, undermines the EU’s digital transformation objectives, and creates perverse incentives for investment in fraud prevention.

The European Parliament and Council’s broader approach to APP fraud liability represents a start for a sound policy that aligns liability with capability, profit with risk, and protection with the EU’s digital ambitions. The challenge now is to implement this framework with appropriate safeguards against both moral hazard and overly restrictive interpretations of gross negligence.

As global financial systems fragment between different regulatory philosophies, Europe has an opportunity to distinguish itself through principled consumer protection. While some jurisdictions may pursue crypto-friendly deregulation or fintech innovation at any cost, Europe can build its competitive advantage on something more fundamental: unwavering trust in payment security. In an interconnected world where financial fraud knows no borders, the jurisdiction that credibly protects consumers from sophisticated scams will ultimately attract both users and legitimate businesses seeking a stable and trustworthy payment infrastructure.

The choice before European policymakers is clear: comprehensive APP fraud protection that builds lasting trust, or fragmented half-measures that perpetuate consumer vulnerability while criminals adapt and evolve.

Please read our proposal for a Shared Liability Framework here.