The European Commission is preparing the Digital Fairness Act (DFA) to tackle manipulative online practices such as dark patterns, addictive design, subscription traps, profiling, influencer marketing, and misleading in-app purchases (adjusting existing rules and directives).

Following the discussion of the Digital Fairness Act Consultation process, BEUC, the European Consumer Organisation, has outlined ambitious demands to strengthen consumer rights.

But one critical issue remains overlooked:

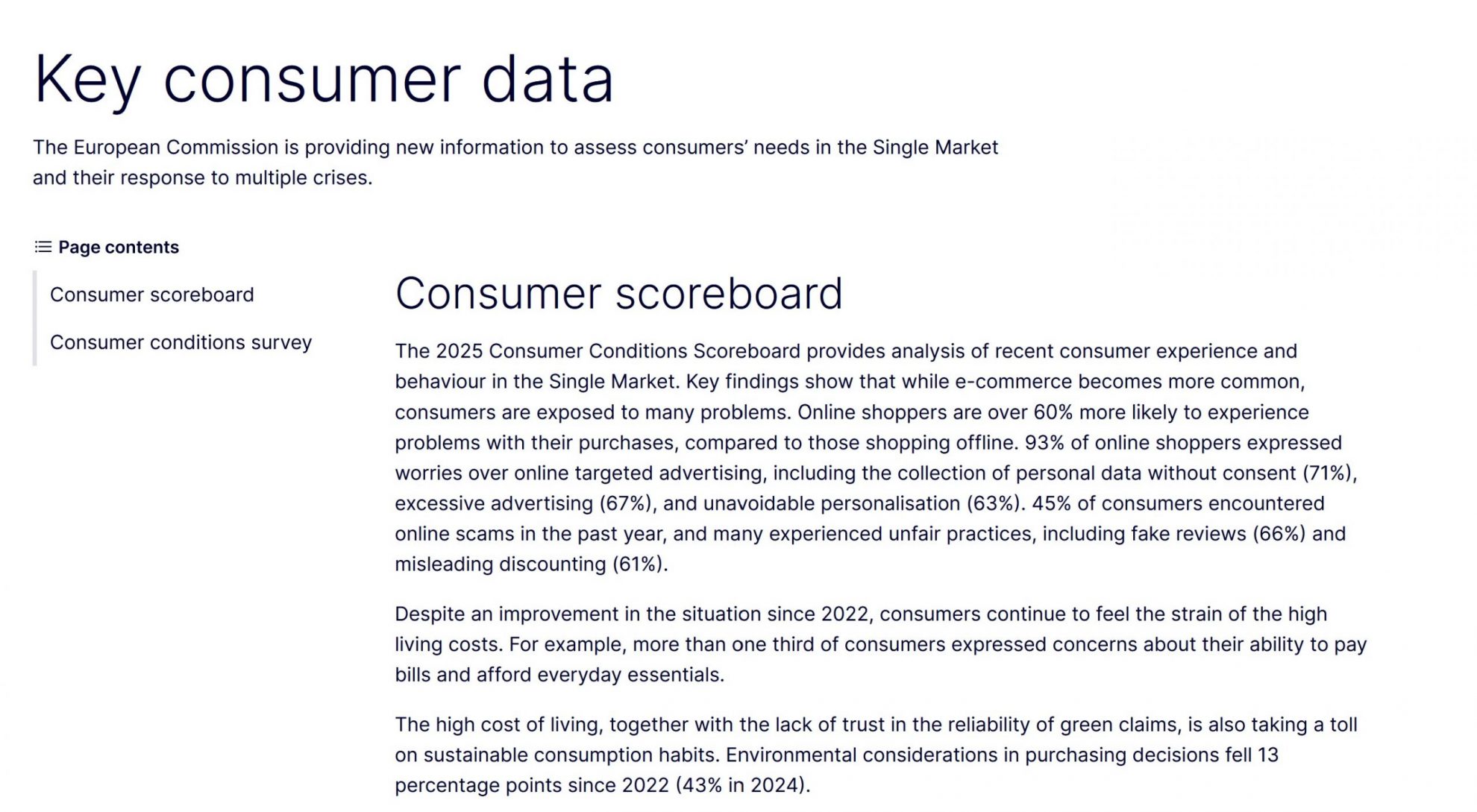

Europe’s main problem is not a lack of laws, but the chronic failure to enforce the ones already in place.

What the Digital Fairness Act is expected to include:

The Digital Fairness Act is promoted to modernise the EU’s core consumer law framework by addressing practices that current legislation only partially captures. According to the Commission’s roadmap and consultation documents, the DFA is expected to introduce explicit rules on dark patterns, stricter obligations for subscription design and cancellation pathways, more precise transparency requirements for personalised offers and profiling, and targeted safeguards for children and vulnerable consumers, especially regarding addictive or manipulative interface design. It will also likely regulate in-app purchases, virtual currencies, influencer marketing, and deceptive presentation of prices or product scarcity. In short, the DFA aims to fill long-recognised gaps in the UCPD, CRD and UTD by creating a more coherent, horizontally applicable digital consumer protection regime. In short, the DFA purports to address long-recognised gaps in the UCPD, CRD and UTD by offering yet another supposedly “coherent”, horizontally applicable layer of digital consumer rules. What remains conspicuously absent, above all, are clear and enforceable liability rules that would actually hold platforms and intermediaries to account.

What BEUC Wants – and the Reality Behind It

1. A modern view of consumer vulnerability

BEUC rightly argues that every digital user is vulnerable to algorithms, nudging and cognitive overload.

They call for updated UCPD standards and recognition of non-economic harm.

Reality: Current laws already allow this protection. Authorities rarely apply it.

2. Fairness-by-design, not manipulation-by-design

BEUC demands a ban on dark patterns, stronger rules for subscriptions and clear design obligations.

Reality: DSA, GDPR and UCPD already prohibit many manipulative practices.

The problem is the absence of consistent enforcement by European authorities.

3. Reversal of the burden of proof

BEUC proposes shifting the burden to platforms once manipulation is indicated.

EFRI agrees—But even today, authorities such as DNB or BaFin are already bound by EU and national freedom-of-information and access-to-documents rules that should ensure transparency. Yet in practice, these obligations are frequently ignored or diluted. This raises an obvious question: if authorites do not comply with the transparency duties they already have, why should anyone expect them or platforms to respect new obligations under another legislative instrument? The real issue is not the absence of legal frameworks but the persistent unwillingness—or inability—of institutions to apply them. Without genuine compliance by authorities themselves, no new law will meaningfully improve consumers’ access to information or accountability.

4. Stronger collective redress

BEUC highlights major procedural barriers in cross-border consumer cases.

They call for streamlined applicable law, improved CPC cooperation and sustainable funding.

Reality: Yes, we agree, but we do not see that the DFA is the right place to address these complex issues.

The Core Issue: Europe’s Enforcement Crisis

Europe already has a sophisticated legal framework:

Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD)

Consumer Rights Directive (CRD)

Unfair Terms Directive (UTD)

Digital Services Act (DSA) – including Article 25 on dark patterns

GDPR – profiling, transparency and consent rules

DMA for gatekeeper platforms.

All of these laws are routinely violated in the digital marketplace.

Yet violations occur daily:

Scam ads run for months on social media.

Platforms fail to verify advertisers.

Payment providers process fraudulent transactions.

Authorities lack resources and technical capacity.

Adding the Digital Fairness Act will not fix this structural deficit.

EFRI’s Position: Prioritize Enforcement

The DFA is useful, but not a solution to Europe’s systemic enforcement gap in consumer protection.

To understand the importance of consumer protection for the democratic stability and for the prosperity of the digital evolution.

technical expertise

proactive and rigit inspections,

Meaningful sanctions.

Conclusion

In our opinion, new laws (hundreds of pages) without effective enforcement risk widening the gap between legal theory and digital reality.

BEUC’s recommendations for the Digital Fairness Act are thoughtful and necessary.

But unless the EU finally strengthens enforcement, consumers will continue to be exposed to manipulation, fraud and unfair digital practices.

Europe does not need more rules—it requires effective enforcement. Now.