In light of recent public commentary by William Schonewille (BarentsKrans), it is important to clarify the core facts in the aftermath of the Dutch class action against Airbnb—and to set the record straight about the roles played.

The Lost WAMCA case against Airbnb!

Since 2021, BarentsKrans, specifically William Schonewille, has served as the law firm representing Stichting Massaschade & Consument (SMC) in the highly publicised case of Dutch Airbnb users charged “double fees.” Under their legal direction, SMC’s mass claim was ultimately defeated. On 11 June 2025, the Court of Appeal in The Hague ruled that Dutch courts lack jurisdiction and that such collective actions must be brought in Ireland. Compounding this, the Dutch Supreme Court had already determined that the relevant Dutch law banning double fees does not apply to short-term lets, such as those on Airbnb, effectively removing the legal basis for pursuing Airbnb double-fee claims in Dutch courts under national law.

The Legal Reasoning behind the Court´s decision!

The legal reasoning behind the Dutch Appeal Court’s decision to reject Dutch jurisdiction over the Airbnb class action, brought by Stichting Massaschade & Consument (SMC) with BarentsKrans as its legal counsel, is firmly rooted in the rules set by the Brussels I Regulation (now formally Regulation (EU) No 1215/2012, known as Brussels I bis). This regulation governs cross-border civil and commercial litigation within the European Union.

General Rule of Defendant’s Domicile

Under Article 2 (now Article 4(1)) of the Brussels I Regulation (Brussels I bis), the general rule is that a defendant domiciled in an EU Member State shall be sued in the courts of that Member State.

Airbnb’s European entity is based in Ireland. Thus, under these rules, Irish courts generally have jurisdiction over civil claims against Airbnb brought by consumers from other EU states

Consumer Forum Rule (Article 18)

Article 18 (consumer contracts) concerns contractual matters; tort claims fall under Article 7(2).

No Distinction for Collective Redress

The regulation does not provide specific rules for collective redress or mass actions.

It treats jurisdiction for collective redress using the same rules as for individual claims, which creates practical obstacles when consumers from multiple countries are bundled into a single action against an EU-based defendant.

This lack of dedicated provisions has always been identified as a major flaw, particularly when the defendant operates cross-border digital platforms, as with Airbnb.

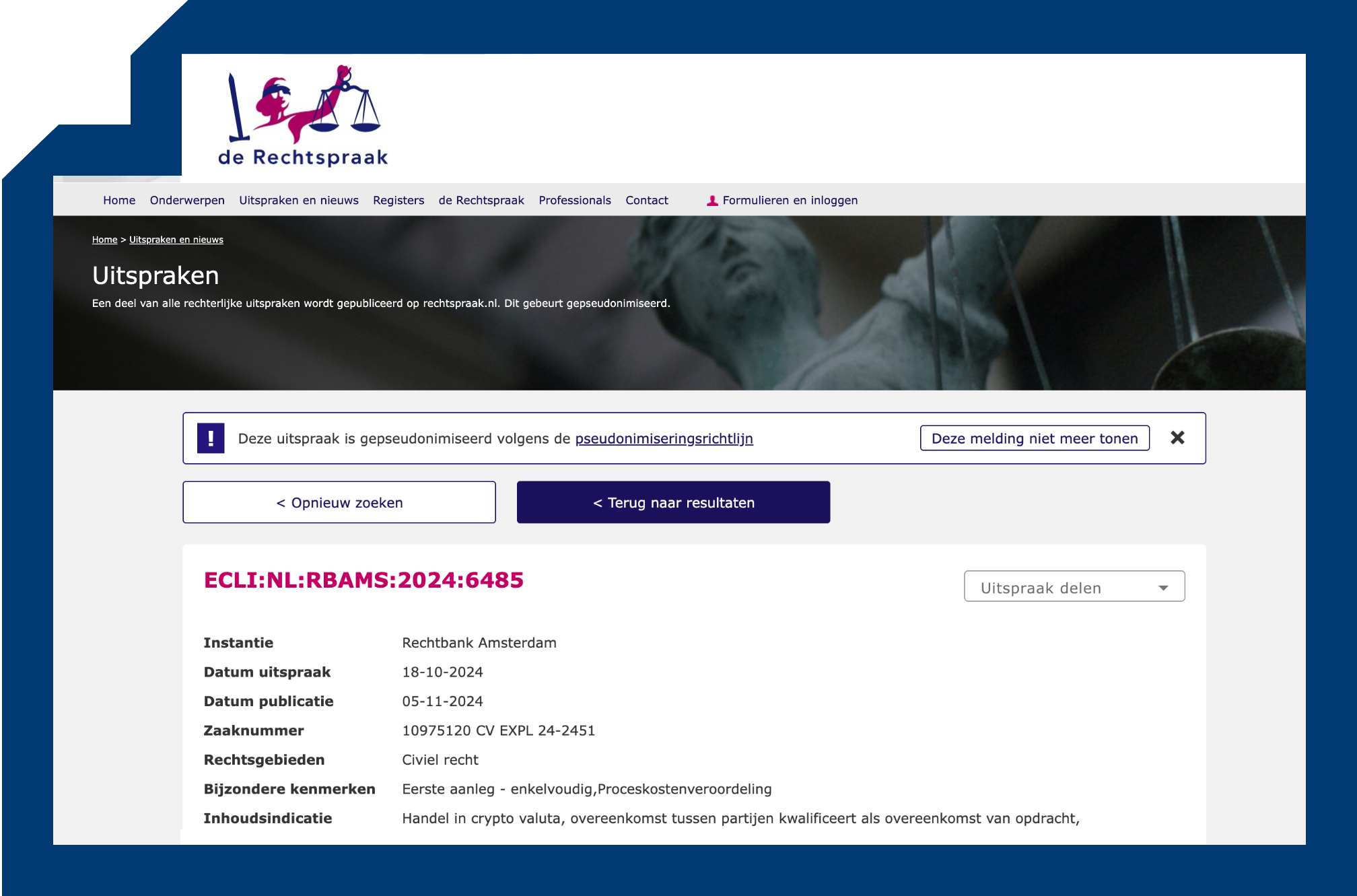

As early as 2021, a Dutch court in Amsterdam held that WAMCA foundations cannot rely on the consumer forum privilege (‘forum consumeris’) under Brussels I bis, as the consumers themselves are not direct parties to the proceedings.

Stichting Massaschade & Consument (SMC) under the lead of William Schonewille appealed citing …. On 10 June 2025 the Dutch appeal court decided that Dutch courts, referencing recent CJEU (European Court of Justice) case law, finally ruled that collective claims filed by WAMCA foundations cannot invoke the “forum consumeris” (home court of the consumer) when the consumers themselves are not directly party to the proceedings so Irish Courts are in charge of Airbnb mass claims.

Only Dutch Courts have an effective system for collective actions (?)

Lawyer William Schonewille of BarentsKrans, the legal advisor for Stichting Massaschade & Consument (SMC) argues in a public blog posting that the court’s ruling gives a ‘particularly consumer-unfriendly interpretation’ of the Brussels jurisdiction rules: “These rules date from the pre-internet era and were last amended in 2012. They are not tailored to collective cases against tech companies that serve millions of European consumers from a single Member State. At European level, the discussion about these rules is still in full swing. Nevertheless, the court has now chosen to apply them strictly – leaving consumers completely powerless.”

Schonewille points out that this ruling exposes a fundamental problem in the legal protection of Dutch citizens: “Individuals who complain about Airbnb can go to the Dutch courts, but as soon as consumers join forces in a collective action, they are referred to Ireland – a country where there is no effective system for collective actions. As a result, large foreign tech companies operating in the European Union remain untouchable as long as they formally establish themselves in an EU country where collective proceedings cannot get off the ground.

Factual Critique: The Irish Collective Action System

Schonewille claims that Ireland remains “a country where there is no effective system for collective actions” is misleading and incorrect as of July 2025.

Ireland implemented Directive (EU) 2020/1828 via the Representative Actions for the Protection of the Collective Interests of Consumers Act 2023, which entered into force on 30 April 2024. By mid-2025, qualified non-profits can (and do) bring collective consumer actions in the Irish High Court. The new system is young, more restrictive, and less tested than in the Netherlands—but it exists and is operational. Publicly available records show Ireland’s courts had already admitted major qualified entities to group proceedings by summer 2025.

Brussels I Regulation—Not Outdated, But Lacking for Collectives

Schonewille is correct that Brussels I (now Regulation (EU) No 1215/2012) was not designed for mass internet-era claims and creates loopholes for consumer class actions. The Regulation is indeed under review at EU level, and features no special jurisdictional privileges for collective redress.

However, the Dutch court accurately and lawfully “applied [the rules] strictly” because it is bound by the Regulation and relevant CJEU precedent. Whether this result is “consumer-unfriendly” is a matter for legislators, not the judiciary. The blame for the result lies as much (or more) with delayed EU legal reforms as with the court’s interpretation.

Experiential Critique: EFRI’s Experience with BarentsKrans/Schonewille:

EFRI, as a former client of William Schonewille and BarentsKrans, experienced serious lapses in professional standards. These included undisclosed conflicts of interest, insufficient transparency in communication, withdrawal from representation shortly before critical deadlines, and attempts to condition refund payments on the suppression of public criticism.

This first-hand experience illustrates a broader issue: while public statements by Schonewille often emphasise regulatory and jurisdictional barriers, they tend to downplay the responsibility borne by representative organisations and their legal counsel in the failure of collective actions. In EFRI’s case, it was not Brussels I bis or procedural complexity that caused the damage. In our view, the decisive causes included counsel’s conduct

The lesson is clear: those who publicly position themselves as defenders of consumer rights must meet the highest standards of loyalty, transparency, and competence. When they fall short, the harm to consumers can be as great as that caused by any legislative gap or court ruling. Schonewille’s framing may appeal rhetorically, but the practical record warrants caution.

Conclusion:

EFRI´s decision to go for WAMCA filing in the Netherlands as Payvision BV and ING Bank NV (its mother company and banking partner) is headquartered in Amsterdam is correct and resolves at least the jurisdictional barriers posed by Brussels I bis.

Schonewille’s statements about the legal landscape are misleading regarding Ireland’s collective action regime as of 2025 and place disproportionate blame on the courts for “leaving consumers powerless,” when the regulatory gap is primarily legislative. Based on recent consumer experience (such as EFRI’s own disputes with BarentsKrans), his framing lacks balance and does not acknowledge the essential role that claimant-side representation plays in the success or failure of mass claims.