The European Union has reached a political agreement on its long-awaited Retail Investment Strategy (RIS), a reform package aimed at encouraging retail participation in capital markets and improving consumer protection.

Yet, the final compromise reveals a familiar pattern: the European financial lobby has once again succeeded in neutralising the most effective consumer-protection tools. What remains is a framework that is heavy on disclosure and procedural checks but light on structural safeguards. So the framework is critically dependent on European enforcement systems that are already known to be weak.

The core failure: kickbacks survive political scrutiny

From a legal perspective, the decisive failure of the RIS is clear: the EU authorities refused to prohibit inducements (kickbacks) in the retail investment distribution chain.

The European Commission initially explored stronger measures to eliminate conflicts of interest where financial advisers receive remuneration from product manufacturers. That ambition collapsed under pressure from:

major financial industry associations,

several Member States protecting domestic distribution models,

and transatlantic asset-management interests.

So, the ban on kickbacks was abandoned before the legislative proposal even reached Parliament, demonstrating the pre-emptive power of financial lobbying in EU financial regulation.

Instead, the RIS allows inducements to continue provided firms can claim that:

a “tangible benefit” exists for the client, and

the inducement is disclosed separately.

From a legal standpoint, this approach is deeply flawed:

“Tangible benefit” is an open-textured legal concept, easily satisfied through internal documentation.

The conflict of interest is not removed, merely administratively justified.

The burden of proof is shifted away from firms and regulators, and implicitly onto consumers.

We agree with BEUC’s criticism. BEUC has consistently argued that only a full ban on inducements can ensure genuinely independent advice.

What the Deal Actually Delivers

Based on publicly reported elements of the compromise, the RIS package introduces:

adjustments to inducement and disclosure rules rather than a clear ban on conflicted remuneration;

product-level “value for money” assessments without hard legal consequences;

strengthened suitability and appropriateness language, but largely within existing MiFID logic;

further reliance on disclosure as a protective mechanism.

So the framing of the outcome as a “win for retail investors” contrasts sharply with the substance of the compromises reached. The watered-down version of the Retail Investment Strategy will surely not result in a boost in the EU financial market’s contribution to our overall competitiveness:

Disclosure Without Enforcement Is Not Protection

From a consumer-protection perspective, the RIS continues a long-standing EU pattern: regulatory refinement without enforcement capacity.

Retail investors in Europe are already subject to extensive disclosures, suitability questionnaires and risk warnings. These mechanisms have demonstrably failed to prevent:

mass mis-selling of complex investment products,

structurally overpriced funds and insurance-linked products,

conflicts of interest driven by commissions and inducements,

systematic under-supervision by national competent authorities.

The RIS does not address the central enforcement gap: rules that exist on paper but are rarely enforced in practice. Without credible supervisory action, additional disclosure obligations merely shift responsibility back to consumers while preserving the existing distribution model.

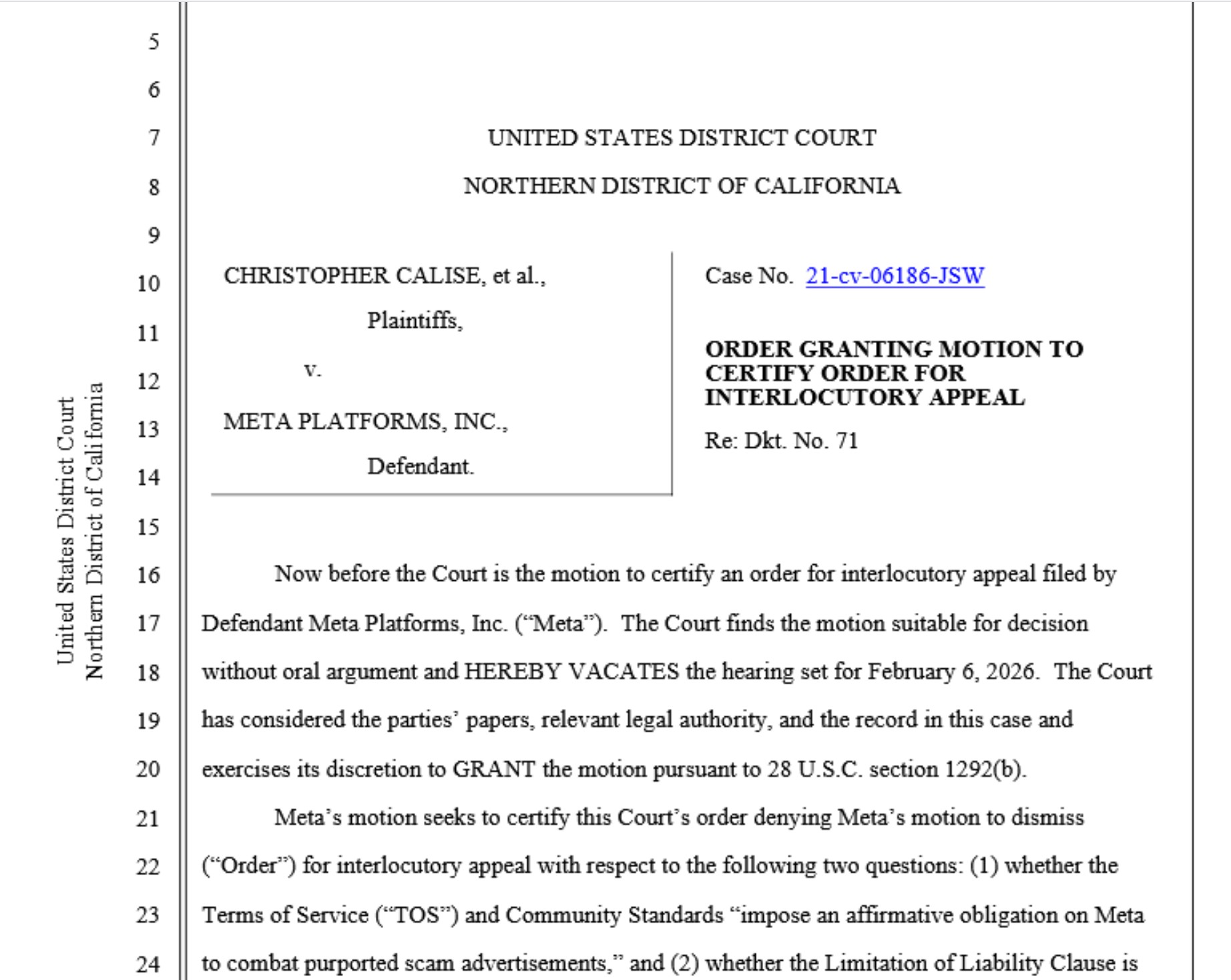

The Enforcement Gap: Europe’s Unaddressed Problem

In practice, retail investor protection in the EU does not fail because of a lack of rules, but because of:

national authorities reluctant to act against large institutions,

procedural barriers for collective redress,

and no coherent EU‑level liability framework that ensures effective redress for retail investors.

The RIS does not introduce mechanisms that would materially change this reality. There is no binding obligation on supervisors to act where consumer harm is systemic, nor are there credible consequences for persistent non-compliance.

Conclusion: A Strategy in Name Only

The Retail Investment Strategy, as politically agreed, appears less like a strategic reset and more like a continuation of the status quo. Encouraging retail participation in capital markets without first restoring trust through effective enforcement is fundamentally flawed.

From EFRI’s perspective, meaningful investor protection requires:

clear liability rules,

enforceable standards,

and supervisory accountability.

Without these elements, the RIS risks becoming another policy package that looks convincing on paper, while leaving retail investors exposed in practice.