As digital assets and cryptocurrencies become more embedded in commercial activity, UK courts are shaping how they’re treated under the law. The legal landscape surrounding digital assets such as cryptocurrencies remains in rapid evolution in the United Kingdom. Recent court decisions in 2019 to 2024 have increasingly addressed critical issues, including property rights, liability for fraud, and duties of care among participants in the digital asset ecosystem. As the legal framework develops, these decisions shed light on the future regulatory and liability environment that fintech companies, investors, and consumers must navigate.

1. Proprietary Remedies and Ownership Clarified in Piroozzadeh v Persons Unknown (2023)

In the case Piroozzadeh v Persons Unknown (2023 EWHC 1024) the High Court discharged an interim proprietary injunction obtained against Binance, holding that the claimant had not given full and frank disclosure at the without-notice stage and that, in any event, damages were an adequate remedy. Critically, the court accepted Binance’s explanation of how deposits are handled—pooled in unsegregated wallets with an account credit to the user—which makes the exchange a potential bona fide purchaser for value and undermines proprietary claims against it.

The claimant was scammed into sending ~USDT 870k (plus fiat) to wallets controlled by fraudsters. Some tokens were traced to Binance “hot” deposit addresses. He obtained without-notice injunctions (including proprietary relief) against “persons unknown” and Binance.

On the return date, Binance applied to set aside the proprietary injunction. The court agreed.

What the court decided (and why)

a. Pooling & account credit ≈ bank model

When users deposit tokens at Binance, the assets are swept into unsegregated, pooled wallets; the user’s exchange account is then credited, and the user has a contractual claim against Binance rather than a segregated, traceable property interest in a specific on-chain output. The judge expressly invoked the bank account analogy: “If a client pays money into a bank account, that bank is not then a constructive trustee.”

Implication: Once pooled and converted into an internal account credit, the exchange can argue it is a purchaser for value; a victim’s proprietary rights are unlikely to survive the deposit, absent notice of fraud.

b. Bona fide purchaser defence should have been disclosed

At the without-notice hearing, the claimant’s team failed to flag obvious defences, including the bona fide purchaser point and the practical difficulty of “preserving traceable proceeds” given pooling. That omission breached the duty of full and frank disclosure, justifying discharge

c. Adequacy of damages

Even putting disclosure aside, the judge noted the claimant had not shown why damages wouldn’t be an adequate remedy as against the exchange (distinct from the fraudsters). This was another basis to lift the proprietary injunction

d. Constructive trust against exchanges?

The court did not decide the ultimate merits on whether an exchange can be a constructive trustee. But it was “deeply sceptical” on these facts, especially given pooling and lack of notice. (The judgment even moots that reverse summary judgment might succeed later.)

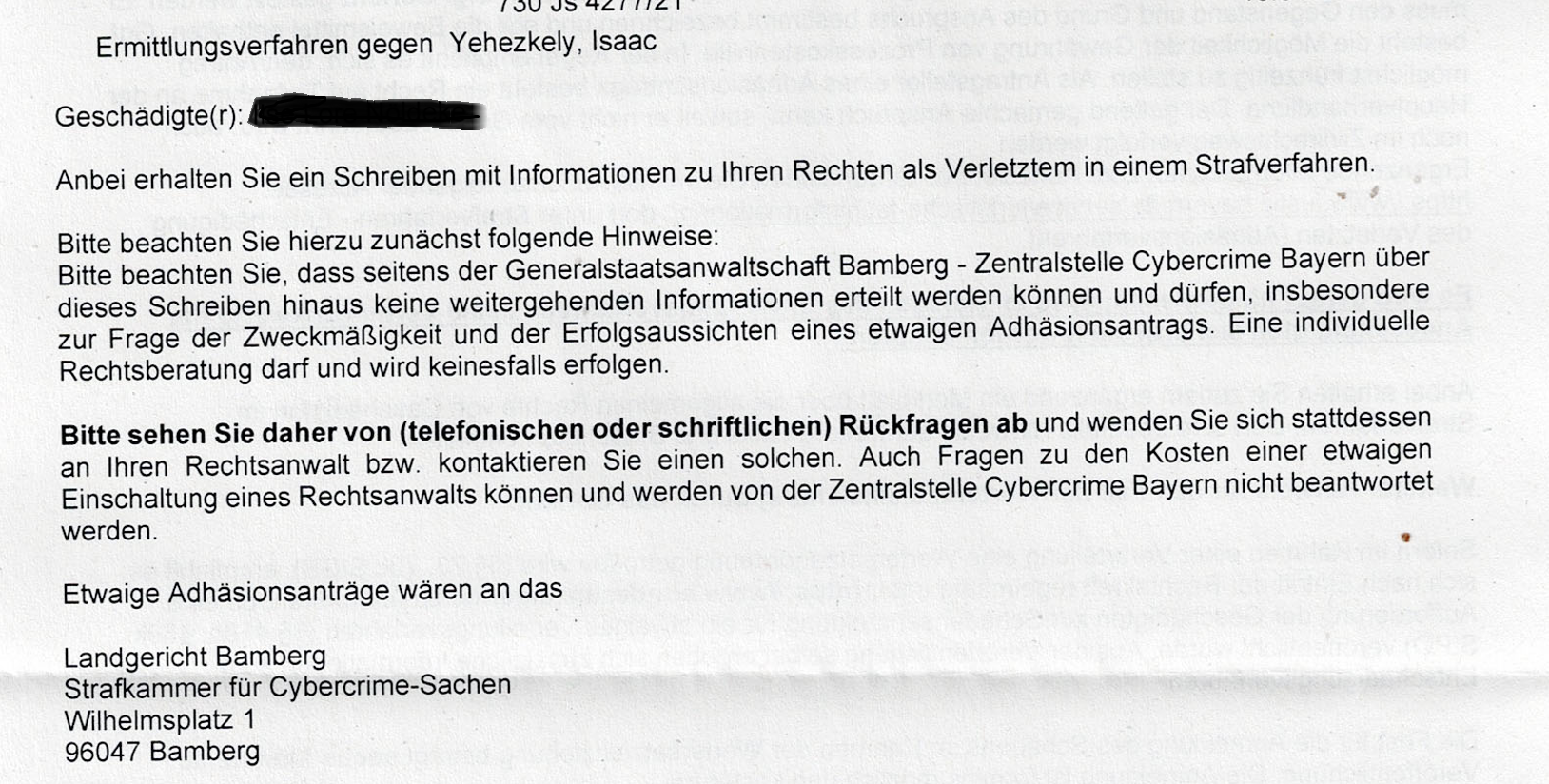

2. Liability for Fraudulent Transfers in DAloia v Persons Unknown (2024)

In July 2024, the High Court of England and Wales delivered its long-awaited judgment in D’Aloia v Persons Unknown.

The claimant, Mr D’Aloia, was deceived by an online trading scam into transferring around £2.5 million in cryptocurrency, including USDT (Tether), to accounts controlled by fraudsters. The stolen funds were then dispersed across multiple wallets and ultimately transferred to several exchanges, including Bitkub, a Thai-based platform that became the sole defendant at trial.

D’Aloia sought to trace and recover his assets through a combination of proprietary claims, constructive trust, and unjust enrichment. The central legal question was whether Bitkub — as an exchange — could be held liable if it had received, knowingly or unknowingly, misappropriated tokens belonging to the claimant.

Although D’Aloia ultimately lost on factual grounds — his tracing evidence failed to show that his specific USDT coins reached Bitkub — the judgment nonetheless broke new legal ground.

a. Cryptoassets Are Property

The court reaffirmed that cryptocurrencies are “a form of property” under English law. They are neither traditional “choses in possession” nor “choses in action,” but represent a distinct third category of property with the characteristics of rivalrous control and persistent digital existence.

This aligns with both AA v Persons Unknown (which first recognised Bitcoin as property) and the Law Commission’s recommendations later enshrined in the Property (Digital Assets etc.) Bill, introduced shortly before the judgment.

b. Following vs. Tracing in a Blockchain Context

The judge carefully explained the difference between following (tracking the same asset) and tracing (tracking substitute assets). The claimant’s expert analysis — which relied on an inconsistent “first-in, first-out” (FIFO) model — was rejected for lack of mathematical coherence and fairness to other victims.

The ruling sends a clear message: claimants must present rigorous, transparent tracing methodologies if they want to recover funds in future crypto-fraud cases.

c. Exchange Liability: Knowledge Is the Key

While Bitkub was exonerated due to the failure of proof, the court expressly confirmed that exchanges can be liable if they receive and retain crypto with sufficient knowledge of the underlying fraud.

If an exchange knows, or consciously disregards, that funds stem from a scam, it may face claims in unjust enrichment or knowing receipt, and could even be treated as a constructive trustee.

This principle represents a major shift: it introduces a path to secondary liability for intermediaries, much like the duties imposed on banks in cases of Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud.

d. The Digital Assets Bill: Confirming, Not Creating, Rights

The court noted that the UK Digital Assets Bill did not change the outcome — it simply codifies what the common law had already recognised. But by formally acknowledging digital assets as property, the Bill strengthens victims’ ability to bring claims and obtain proprietary injunctions against exchanges.

3. Duties of Care and the Tulip Trading Litigation

The Tulip Trading Ltd v van der Laan case drew significant attention for exploring whether developers and miners owe duties of care to cryptocurrency holders.

Court of Appeal (Feb 3, 2023) held there is a serious issue to be tried that Bitcoin “core” developers may owe fiduciary (and possibly tortious) duties to coin owners—overturning the 2022 High Court’s summary dismissal. The case later did not go to a merits judgment: the related 2024 High Court rulings in the COPA/Wright litigation record that the Tulip claim was discontinued. So Tulip sets the door-ajar doctrinal marker—but leaves ultimate liability undecided.

Claimant: Tulip Trading Ltd (TTL), associated with Dr Craig Wright. TTL said a 2020 hack deprived it of access to private keys controlling billions in BTC/BSV/BCH. It asked the court to require network developers to implement a code patch/fork restoring its access.

Defendants: groups of Bitcoin/BSV/BCH developers (including Wladimir van der Laan).

Procedural journey (why this case mattered)

High Court (2022): Falk J summarily dismissed TTL’s claim: developers owed no fiduciary duty or common-law duty of care to coin holders; no obligation to write software to help users regain access.

Court of Appeal (2023): Birss LJ (Lewison & Popplewell LJJ agreeing) said TTL’s case on developer duties is arguable and should go to trial. The court emphasised the need to test whether “the decentralised governance of Bitcoin really is a myth.

Aftermath (2024): In the COPA v Wright suite, the High Court noted the Tulip claim had been discontinued (no final determination on duties).

What the Court of Appeal actually said (key points):

Arguable fiduciary duty: Developers exercise discretionary power affecting others’ property (protocol decisions; implementing or rejecting patches). On those pleaded facts, it’s not fanciful that they could owe fiduciary duties—e.g., to act in good faith and not to abuse their position vis-à-vis owners. Whether such duties exist in law depends on facts tested at trial.

Possible duty to act (positive duties): The CA accepted it was arguable that duties might extend to taking reasonable steps (even code changes/forks) to help a proven owner regain control—subject to network integrity and competing interests. The court did not decide the duty exists; it only cleared the jurisdictional hurdle.

Tort claims track fiduciary analysis: If a fiduciary duty is arguable, tortious duties (e.g., a duty of care) may also be arguable, but the point would ride on the same factual matrix.

Why Tulip still matters (despite discontinuance):

Doctrinal opening: Tulip is the first appellate authority to say developer-duty claims are not hopeless. It keeps alive the possibility that, in some circumstances, protocol maintainers could owe duties to asset holders.

Litigation strategy: Claimants can credibly plead fiduciary/tort duties where developers’ real-world governance looks centralised (gatekeeping commits, decision rights, emergency controls). Exchanges and developers will point to decentralisation and policy harms of court-mandated patches.

Current state of play: There is no merits ruling imposing such a duty. For now, D’Aloia is the practical path: prove tracing + exchange knowledge for liability; Piroozzadeh shows limits on proprietary remedies once assets are pooled at exchanges. Tulip remains the “what if” case.

One-paragraph takeaway for practitioners

Across D’Aloia (2024), Piroozzadeh (2023), and Tulip (CA 2023): treat crypto as property in principle, but expect proprietary remedies to falter once assets hit pooled exchange wallets unless you can prove receipt of your value and the exchange’s knowledge (D’Aloia). In practice, win the expert battle on tracing (disclose and stick to a coherent method), plead beyond property (add knowing receipt, dishonest assistance, unjust enrichment with a tight “at the expense of” theory), and prioritise information/freezing orders against the fraudsters, using exchanges mainly for disclosure and targeted, knowledge-based claims. For governance-layer angles, Tulip permits developer-duty arguments only where control looks centralised; developers should document decentralisation and process hygiene. Exchanges should double-down on KYC/AML, alerts, freezes, and audit trails, because actual notice or wilful blindness is the pivot that turns compliant infrastructure into liability exposure.

Conclusion: Digital Asset Liability Laws evolve

UK case law now sketches a workable framework: property status is clear, proprietary recovery narrows at the exchange gate without receipt+knowledge, and developer duties remain an open, fact-sensitive question. As legislation beds in, stakeholders should monitor how courts apply knowledge standards, scrutinise tracing evidence, and treat protocol governance—because those pressure points will drive outcomes in the next wave of crypto-fraud litigation.