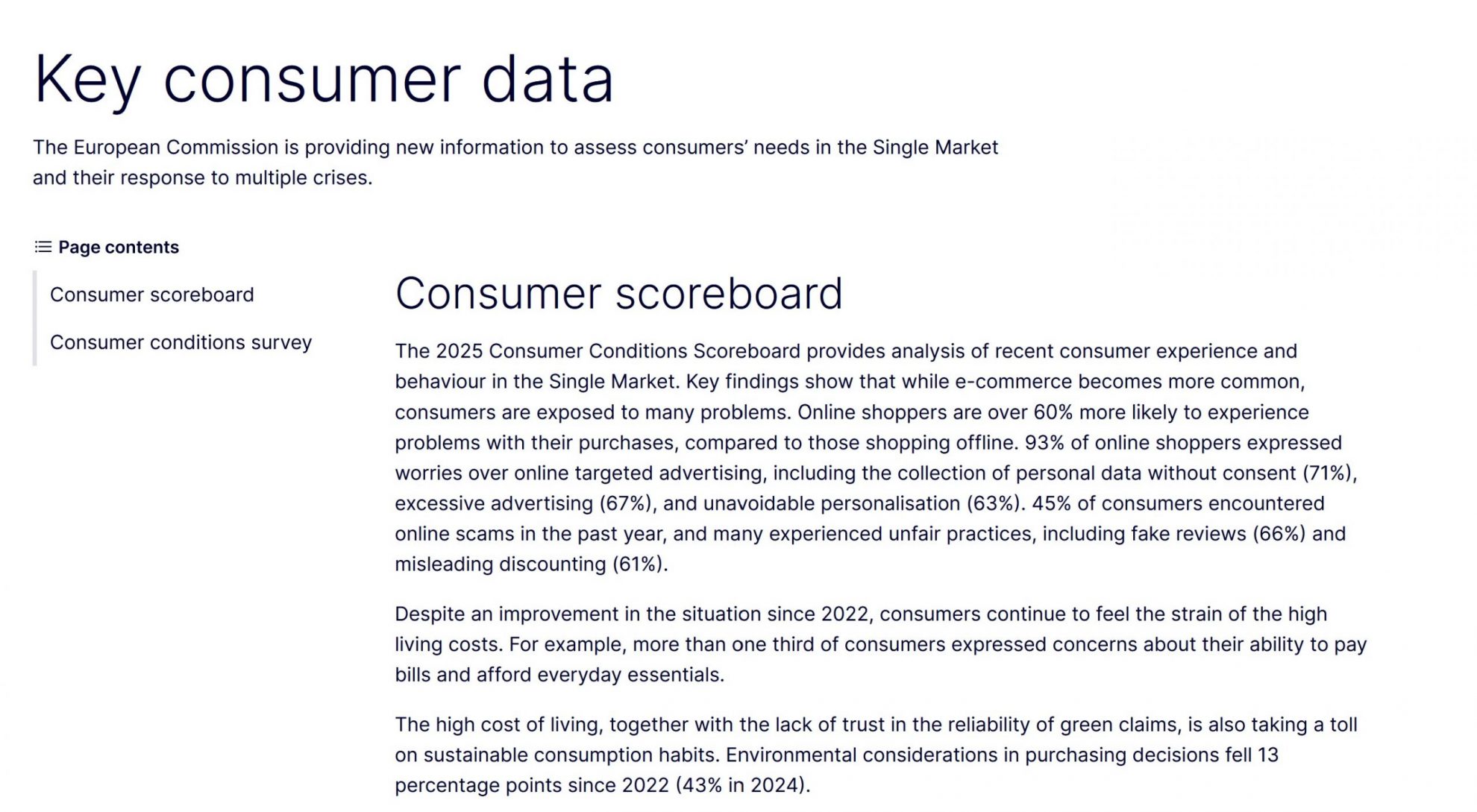

The European Commission’s recent ADR reform package —touted as a step forward—amounts to little more than regulatory window dressing. It tweaks reporting obligations, mandates faster response times, and modestly expands the scope of covered disputes. But it deliberately avoids the core issue: the absence of binding authority and enforceable obligations for traders and financial institutions. As long as banks can participate in ADR processes without any legal duty to comply with outcomes, the entire system remains a hollow ritual—designed more to deflect political scrutiny than to protect consumers. These reforms are not a cure—they are a deliberate attempt to preserve a failed system while pretending to modernize it

ADR’s Regulatory Promise vs. Systemic Failure

The European Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) framework was established through the ADR Directive (2013/11/EU) and the Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) Regulation (524/2013), creatingcomprehensive consumer protection infrastructure. The FIN-NET network, created specifically for financial services disputes, promised efficient cross-border resolution mechanisms that would enable fraud victims to seek redress regardless of jurisdictional complications.

For payment fraud victims, this framework theoretically provided multiple avenues for relief when banks systematically denied reimbursement claims. National financial ombudspersons were positioned as accessible alternatives to costly litigation, while the ODR platform promised streamlined resolution for cross-border fraud cases that characterize contemporary criminal operations.

The Reality of Systematic Consumer Abandonment

EFRI’s empirical research exposes the stark disconnect between the promises of the European ADR framework and the lived realities of payment fraud victims. Among the 1,685 documented fraud cases, only victims based in the United Kingdom reported successful outcomes after turning to the British Financial Ombudsman. In contrast, every single EU victim who sought assistance from domestic or foreign ombudsman institutions was rejected. Not one received meaningful redress. This amounts to a 100% failure rate within the ADR system for the most vulnerable consumers. In all EU cases, the only “support” offered was a referral to law enforcement—an abdication of the consumer protection mandate these institutions are meant to uphold.

This is exemplified by the Danish Financial Complaint Board’s performance, which EFRI sharply critiques as further evidence of structural ADR dysfunction. It took the Board 17 months to conclude that it lacked jurisdiction over the case—ultimately advising the victims of Københavns Andelskasse to pursue costly and protracted civil litigation instead. This outcome represents a serious institutional failure and stands as a disgrace to the very purpose of alternative dispute resolutionthat they are not in charge and that the victims of Kobenhavn Andelskasse should turn to civil courts (a pure disgrace).

Structural Design Ensures Consumer Defeat

Non-Binding Authority and Voluntary Participation:

The core structural flaws of the European ADR framework lie in its lack of enforceability and the discretionary approach to trader participation. The ADR Directive leaves it to each Member State to decide whether participation in ADR procedures is mandatory for traders. As a result, only 23 of more than 60 financial ombudsman bodies across Europe have binding decision-making authority. The rest operate under voluntary compliance, which financial institutions frequently ignore without consequence. This creates a façade of consumer redress while allowing PSPs to participate in ADR processes with no obligation to implement the outcomes—particularly when those outcomes are unfavorable.

Resource Inadequacy by Design:

European ADR systems suffer from chronic underfunding, which appears to be an intentional design flaw rather than a resource constraint.

Invisibility and Inaccessibility:

Despite legal requirements for transparency, most fraud victims remain unaware of ADR mechanisms. Payment Service Providers (PSPs) formally comply with information obligations by embedding vague ADR references deep within their general terms and conditions, rather than proactively informing or educating consumers. This formalistic approach ensures that even the theoretical remedies offered by ADR remain practically inaccessible.

Procedural Barriers That Favor Institutional Defendants

Timeline Manipulation: Although ADR Directive envisages a 90‑day resolution, fraud cases often stretch 3–9 months, adding undue pressure on financially distressed consumers.

Burden of Proof: Victims must prove bank misconduct rather than banks proving compliance—an unrealistic standard in fraud involving organized operations.

Hidden Costs & Complexity: Fees, procedural rules, language barriers and digital literacy requirements disproportionately impact elderly and marginalised victims

The Illusion of Reform: Recent European Commission Initiatives

Legal scholars and consumer advocates have long criticized the European ADR framework as structurally incapable of delivering justice. Caroline Cauffman sharply concluded that the ADR Directive merely institutionalizes a second-rate system of justice for consumers—one that fails to meet basic standards of fairness and redress, particularly in cross-border disputes.

Even the European Commission’s evaluation in 2023 conceded that the ADR system is largely ineffective in practice, citing low consumer trust, poor cross-border functionality, and deep fragmentation across Member States as unresolved issues—more than a decade after the Directive’s adoption.

Multiple EU-level institutions have further exposed the system’s lack of enforcement power, opaque procedures, and total absence of accountability mechanisms, making it abundantly clear: the current ADR architecture protects institutions, not consumers

This undermines any claim that the ADR framework acts as an effective remedy for consumers—especially in complex, cross-border payment fraud cases—confirming EFRI’s position that the system serves institutional theatre, not justice

Reforms Offer Cosmetic Fixes, Not Structural Change

As a consequence of the ongoing discussions on 26 June 2025, the Council and Parliament reached a provisional trialogue agreement to modernise ADR, adding mandatory response deadlines and better cross‑border coordination—but preserving voluntary compliance for the majority of ADR bodies.

These “reforms” improve form but not substance, allowing institutions to continue ignoring negative decisions without legal consequence.

These “reforms” are not a cure—they are a deliberate attempt to preserve a failed system while pretending to modernize it.

This outcome is no coincidence: it reflects the success of sustained lobbying efforts by financial industry groups that have systematically opposed the creation of any effective redress mechanism that could hold institutions meaningfully accountable to defrauded consumers.

The Systematic Enablement of Consumer Exploitation

European ADR systems function as performative mechanisms whose real effect is to shield institutions and channel frustration into failure. EFRI’s documented 100% failure rate among fraud victims who attempted EU ADR institutions reflects a design serving institutional interests—not consumer justice.