On 6 November 2025, the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) announced enforcement action against Coinbase Europe Limited for serious anti-money laundering (AML) monitoring failures, imposing a monetary penalty of €21,464,734 (discounted from €30,663,906 under the settlement scheme; subject to High Court confirmation).

What the regulator found

Scope of failure: Configuration faults in Coinbase Europe’s transaction-monitoring system meant 30,442,437 transactions—about 31% of activity in the affected period—were not properly monitored. The unmonitored flow exceeded €176 billion.

Delay and consequences: It took almost three years for Coinbase to complete monitoring of the impacted transactions, which then produced 2,708 Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) to Ireland’s FIU—flagging suspected money laundering, fraud/scams, drug trafficking, cyber-attacks (malware/ransomware), and child sexual exploitation.

Legal basis: CBI found breaches of transaction-monitoring obligations under Ireland’s Criminal Justice (Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing) Act 2010, across 23 April 2021 – 19 March 2025. Failures also included missing or inadequate internal policies, controls, and procedures, plus insufficient additional monitoring on 184,790 transactions.

CBI underscored that real-time monitoring and prompt STRs are foundational to an effective AML/CFT regime: “The failure of such a system within any financial institution creates an opportunity for criminals to evade detection.

Why this matters

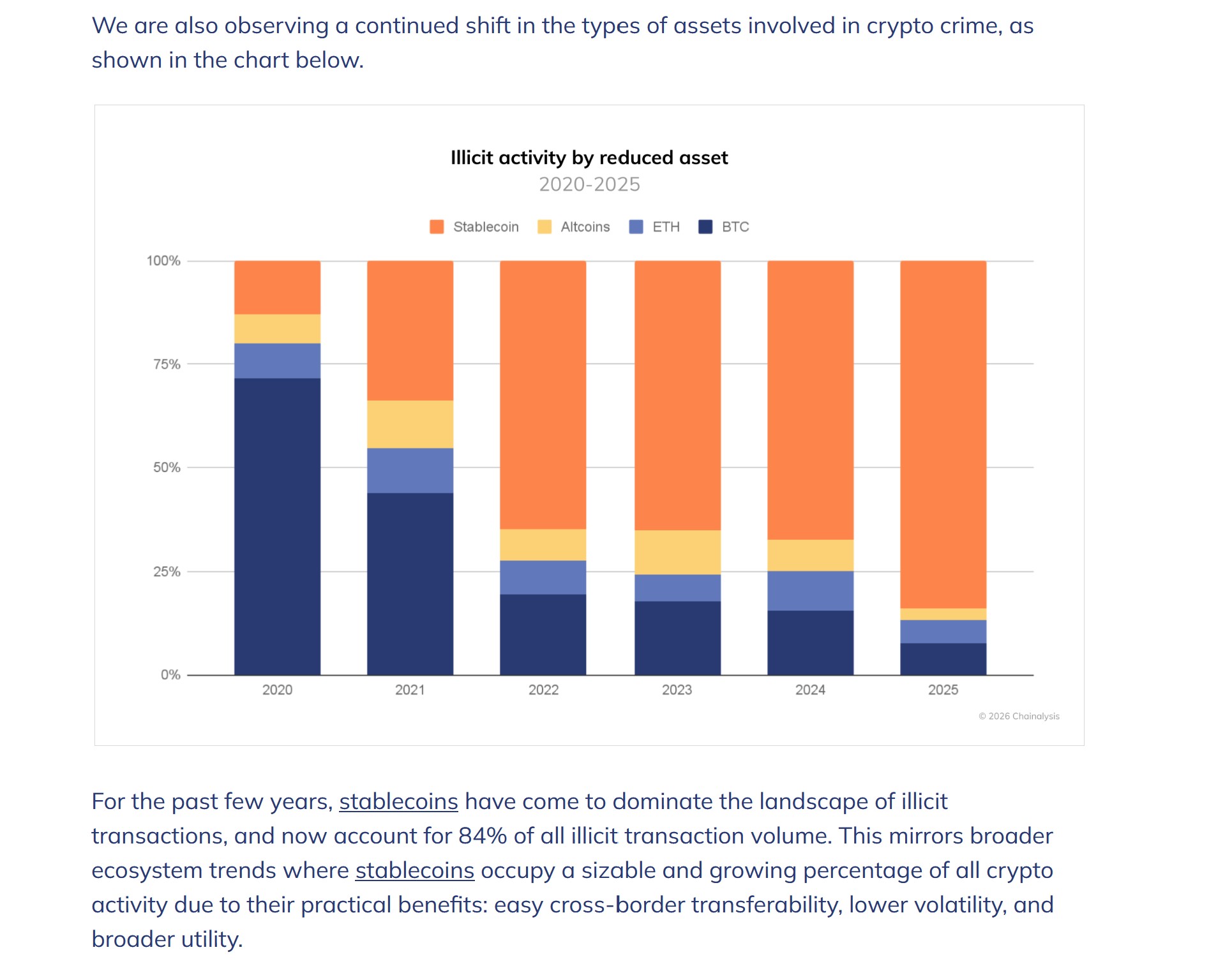

In the U.S. alone, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center logged 149,686 crypto-related complaints in 2024 with $9.3 billion in reported losses, a 66% year-on-year increase; within that, crypto-investment scams accounted for $5.8 billion.

When a regulated VASP leaves a third of its flows effectively unscreened—even for a year—the detection window for criminal proceeds widens. Retroactive monitoring years later cannot fully remediate the missed disruption, freezing, and tracing opportunities for victims and law enforcement. For consumers and fraud victims, delayed STRs can mean irretrievable losses, stalled investigations, and prolonged exposure to repeat victimization.

Is there a liability for online fraud victims based on the ML findings

AML/CTF failings do not automatically create civil claims for victims;

Any compensation claims hinges on negligence. Under Irish law, third-party recovery requires a duty of care (foreseeability, proximity, and that liability is fair, just and reasonable)—and UK/Irish doctrine limits the bank-style Quincecare duty to protecting a bank’s own customer, not outside victims of authorized payments. That said, a targeted claim becomes viable if victims can prove (i) Coinbase (or its EU entity) had specific knowledge of fraud-linked wallets/merchant accounts or monitoring defects affecting identifiable clusters, (ii) failed to act promptly (freeze/offboard/notify/file) after that knowledge, and (iii) the claimant’s loss occurred after the knowledge date—i.e., incremental harm caused by continued processing. For Netherlands-based angles, the bank-specific Safe Haven duty does not automatically apply to PSPs/VASPs; claims must be framed under Art. 6:162 BW (general tort) using hard red-flag evidence (e.g., extreme chargeback programs, regulator warnings, transaction-laundering patterns), with Wwft breaches serving as evidence of negligence rather than a stand-alone private right (EFRI argues the Payvision case based on these arguments).

Bottom line: fines show supervisory breaches; victim liability turns on knowledge + inaction + post-knowledge loss, proven with discovery-grade facts.