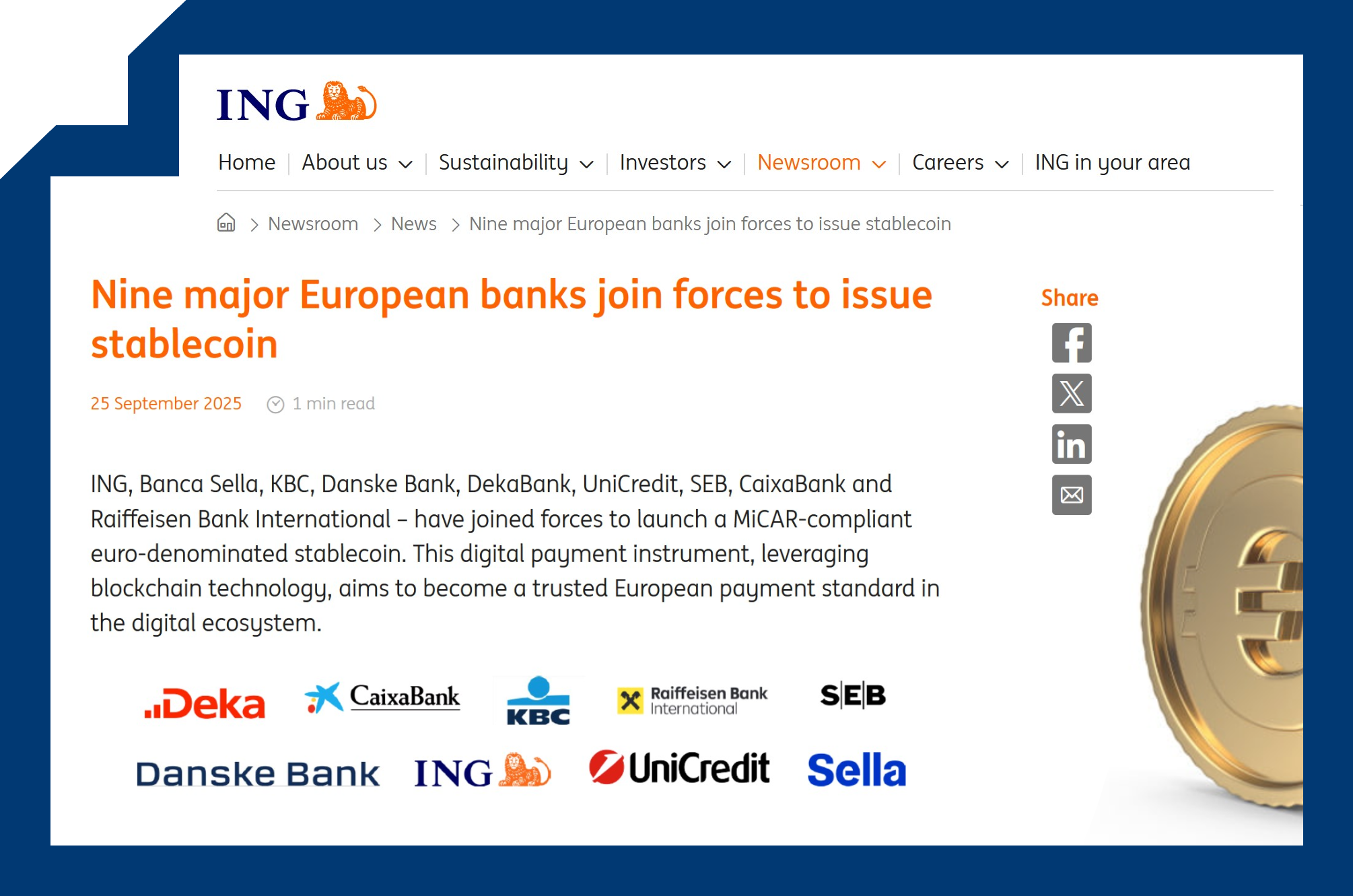

When ten of Europe’s largest banks announce a joint venture to issue a new euro stablecoin, the industry celebrates it as innovation, digital sovereignty and a long-overdue counterweight to US players like Circle or Tether. This is the narrative surrounding Qivalis, the new Dutch company that aims to launch a MiCA-compliant Qivalis euro stablecoin in 2026, backed by ING, UniCredit, Raiffeisen Bank International, KBC, SEB, CaixaBank, Danske Bank, DekaBank, Banca Sella and now BNP Paribas.

A New Euro Stablecoin – And an Old Power Struggle

At first glance, this looks like a positive step for Europe. The continent has fallen behind in the stablecoin race and the euro barely exists in tokenized form. A consortium of big banks promising a regulated, fully backed euro-denominated stablecoin should, in theory, be welcome. But anyone who has followed the battle around the digital euro project of the European Central Bank (ECB) knows that there is a much darker strategic layer behind this initiative

The Digital Euro the Banks Do Not Want

For years, Europe’s banking lobby has fought hard to prevent a strong, user-friendly digital euro issued directly by the ECB. Bank associations warn of deposit flight, emphasize balance-sheet risks and lobby intensively to limit the central bank’s role to a bare minimum. The European Central Bank (ECB) has already responded with generous concessions: no interest on digital euro holdings, strict balance limits and a narrow focus on payments.

In other words, the digital euro has been designed with features that limit its attractiveness as a large‑scale deposit alternative to commercial banks, notably non‑remuneration and strict holding limits A genuine public digital euro would give ordinary citizens direct access to risk-free central bank money, outside the insolvency risk and opacity of private intermediaries. That is precisely what the banks fear.

Qivalis as the Banks’ “Private Digital Euro”

Now, just as political negotiations on the digital euro legislation reach their final stage, the same banks present their own version of a “digital euro”. It is not a public monetary instrument and not a form of central bank money. It is a private, bank-issued token, fully controlled by the very institutions that fear the ECB’s public alternative.

Seen in this light, the Qivalis stablecoin is not a neutral innovation story. It is a power play. The structure is designed as e-money under MiCA, which means that every token represents a claim against the issuing institution, not against the Eurosystem. This preserves the traditional model where banks keep consumer deposits on their balance sheets and continue to earn on them.

A real digital euro, by contrast, would sit outside commercial bank balance sheets and would reduce the dependence of citizens and merchants on specific banking groups. Qivalis keeps that dependence fully intact and simply moves it onto a tokenized infrastructure

From “Compliance Risk” to Structural Control

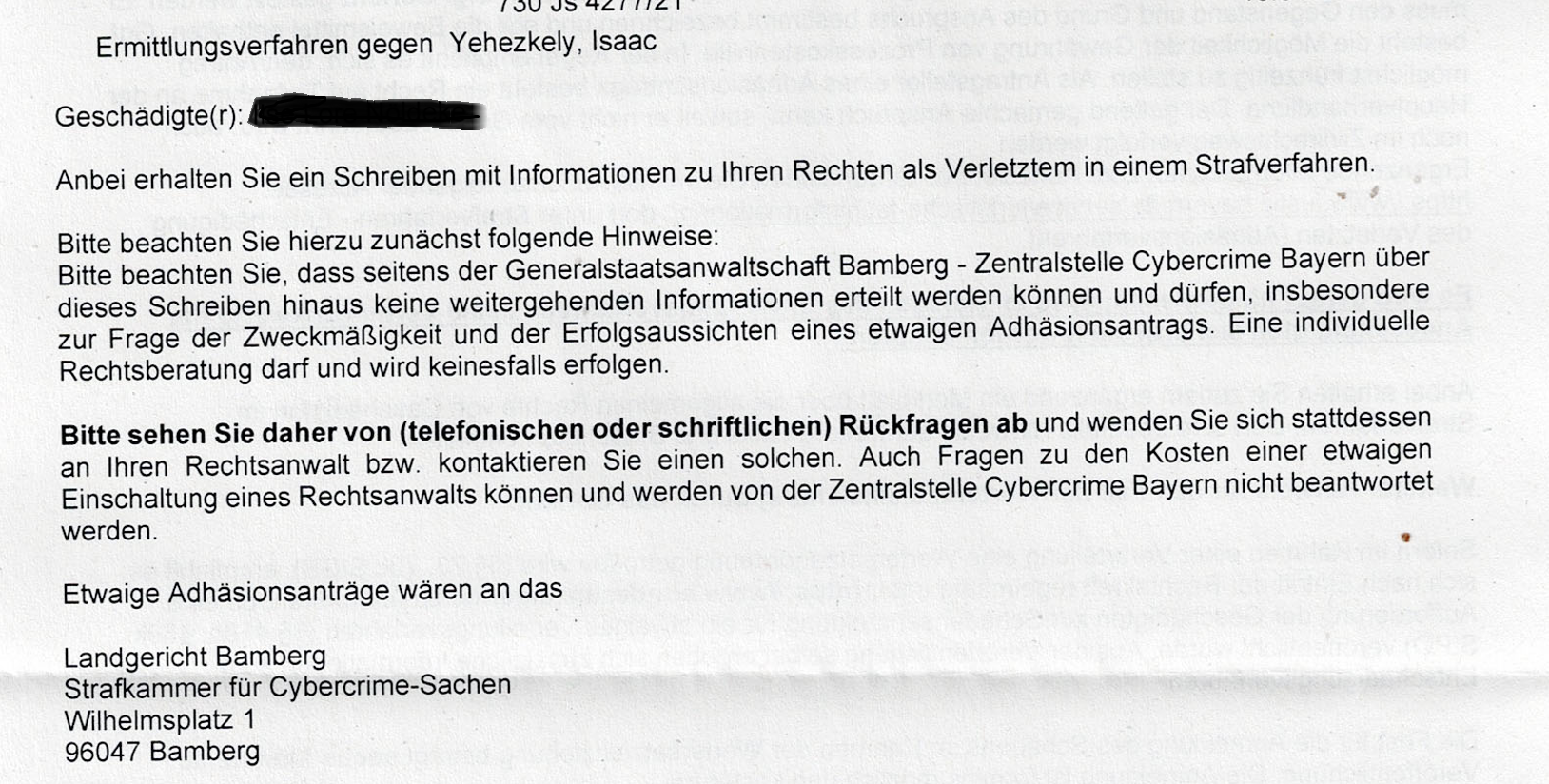

In our first article on this topic, “European Banks’ Euro Stablecoin – A Compliance Risk?” (available at: https://efri.io/european-banks-euro-stablecoin-a-compliance-risk/), we highlighted the obvious contradiction: the same banks that have accumulated a long history of AML and sanctions failures now present themselves as guardians of Europe’s tokenised money.

That analysis focused on compliance and AML risk: persistent supervisory findings against ING, UniCredit, Danske Bank and others; unresolved legacy issues; and a pattern where commercial interests repeatedly trumped robust financial crime prevention. If those institutions now run a pan-European euro stablecoin, the risk is clear. They may simply digitise yesterday’s governance blind spots with tomorrow’s payments technology.

This second article looks at a deeper structural problem: Qivalis is not just a compliance risk. It is also a strategic instrument that helps the banks contain and neutralise the digital euro project of the ECB.

Digital Sovereignty as a Convenient Narrative

Supporters of Qivalis insist that this project serves “European digital sovereignty.” They argue that Europe should not rely on US stablecoin issuers and US card schemes for its digital payments infrastructure. On the surface, this sounds reasonable, and it will certainly appeal to policymakers who are uneasy about American dominance in payments and crypto.

However, this framing conveniently hides a different goal. Instead of building public infrastructure under the control of the Eurosystem and subject to democratic accountability, the banking sector seeks to occupy the same space with a privately controlled stablecoin. Qivalis is presented as a sovereignty project, but in practice it cements private dominance over the future of digital euro payments.

No New Rights for Consumers and Fraud Victims

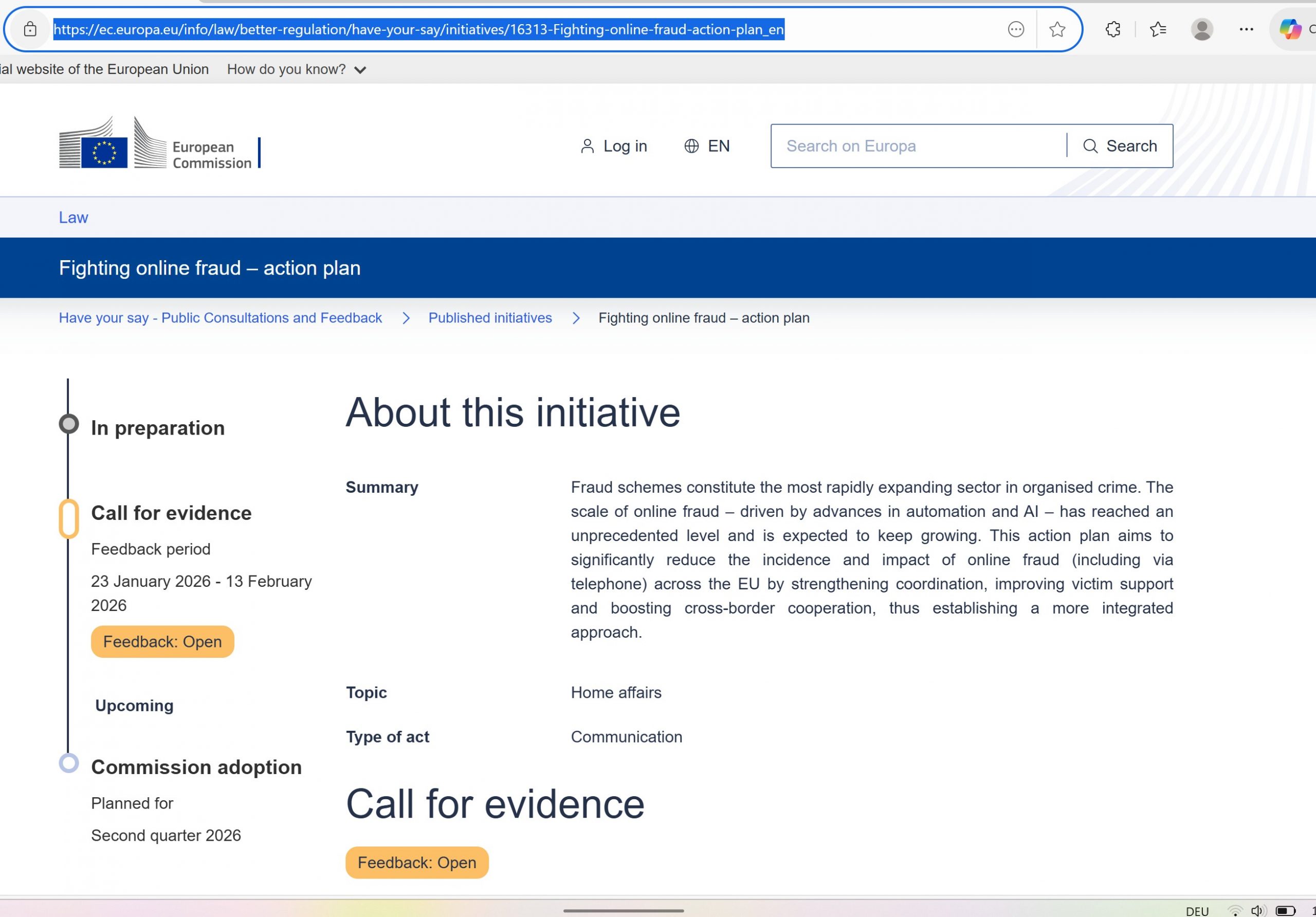

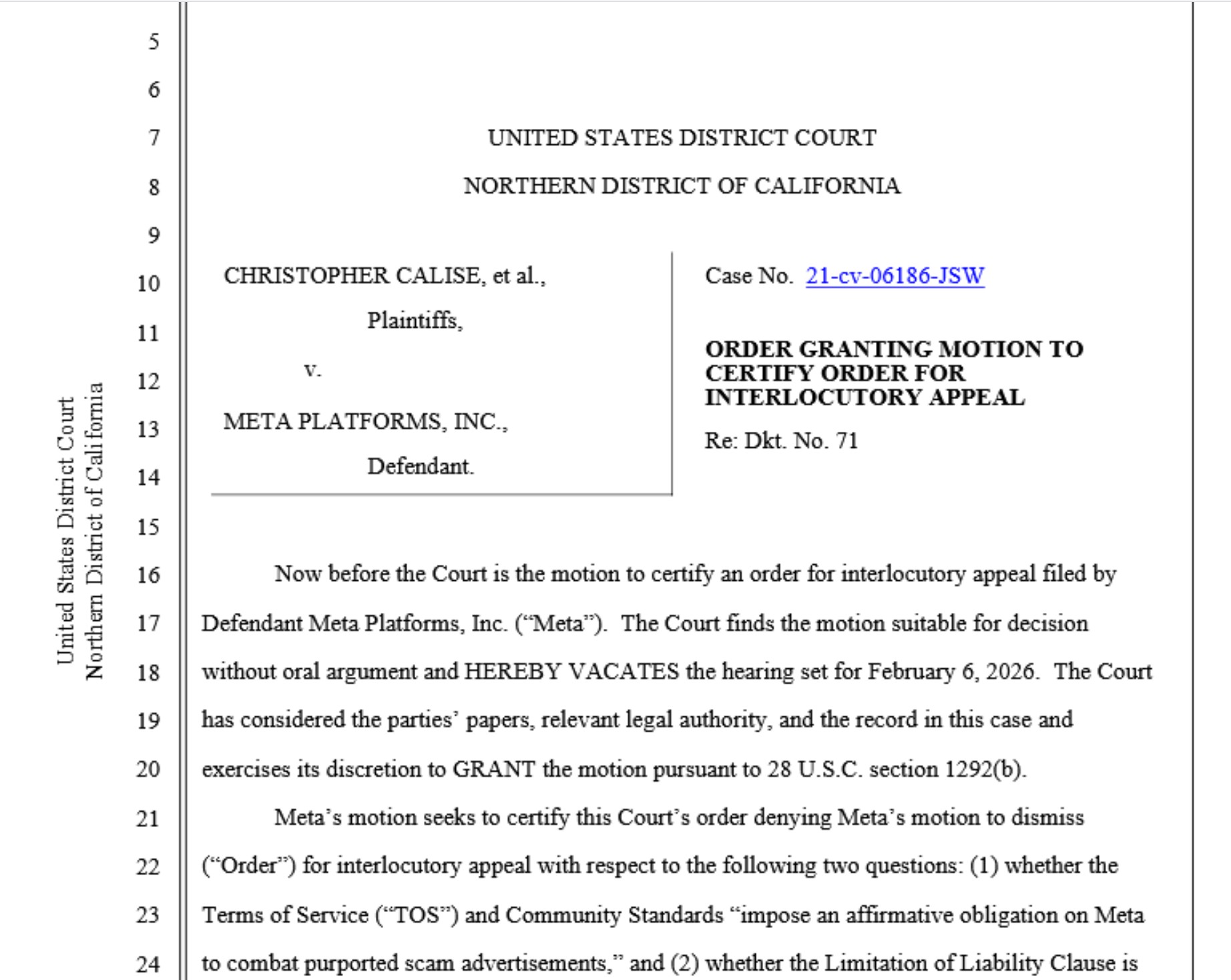

There is also no indication that Qivalis intends to improve consumer protection, APP fraud reimbursement or dispute resolution. Europe experiences a constant rise in APP fraud and cross-border cybercrime. At the same time, the banking sector systematically resists meaningful reimbursement obligations and shifts responsibility to consumers, as we have documented repeatedly in our work on PSR and PSD3.

A private euro stablecoin issued by banks does not change this behaviour. It simply creates another proprietary layer where refund rules, chargeback mechanisms and complaint handling remain in the hands of the same institutions that are currently fighting any expansion of liability in PSD3 and the Payment Services Regulation. For victims of online investment fraud and payment scams, there is no promise of better protection. They are merely invited into a new, tokenized environment governed by the old rules.

Timing Against the ECB’s Digital Euro

The timing of Qivalis is equally revealing. The euro stablecoin is scheduled to launch in the second half of 2026, years before the ECB’s digital euro can realistically reach the market. Once a bank-run stablecoin is established and distributed directly through Europe’s retail banking apps, political appetite for a strong public digital euro will inevitably decrease.

Policymakers may eventually argue that a private “euro stablecoin” backed by big banks makes the ECB’s project redundant. For the banks, that would be the perfect outcome. They maintain their gatekeeper role, their fee structure and their control over digital payments, while presenting the result as a success story for European innovation and MiCA compliance.

What Regulators Should Ask Before Approving Qivalis

If European authorities, especially De Nederlandsche Bank and the ECB, take their mandates seriously, they should not treat Qivalis as a neutral technical upgrade. They should ask some basic political and systemic questions:

- Does this stablecoin strengthen or weaken the role of public money in Europe?

- Does it create new paths for fraud, misconduct and opacity in cross-border transactions?

- Do the governance and AML track records of the member banks justify entrusting them with such a central role in the euro’s digital future?

- And most importantly: does the Qivalis project make it harder for the ECB to introduce a genuine public digital euro that would finally give citizens and merchants a safe, universal digital payment instrument?

These are not abstract questions. They go to the heart of who controls money in a digital economy: democratically accountable public institutions, or private banking groups with a long record of compliance failures.

Conclusion: A Stablecoin That Protects Bank Power, Not Consumers

For fraud victims and ordinary European consumers, Qivalis should ring alarm bells. A digital euro issued by the ECB would have offered a stable, public, risk-free and politically accountable payment instrument, directly anchored in the Eurosystem. The Qivalis euro stablecoin offers none of that.

It offers the appearance of European progress while cementing private dominance in the most sensitive area of the digital economy: the creation and control of money. Europe must decide whether digital payments will serve the public interest or the balance sheets of commercial banks that have repeatedly shown indifference—even hostility—towards retail customers. Qivalis blurs that choice, but it exposes exactly what is at stake.