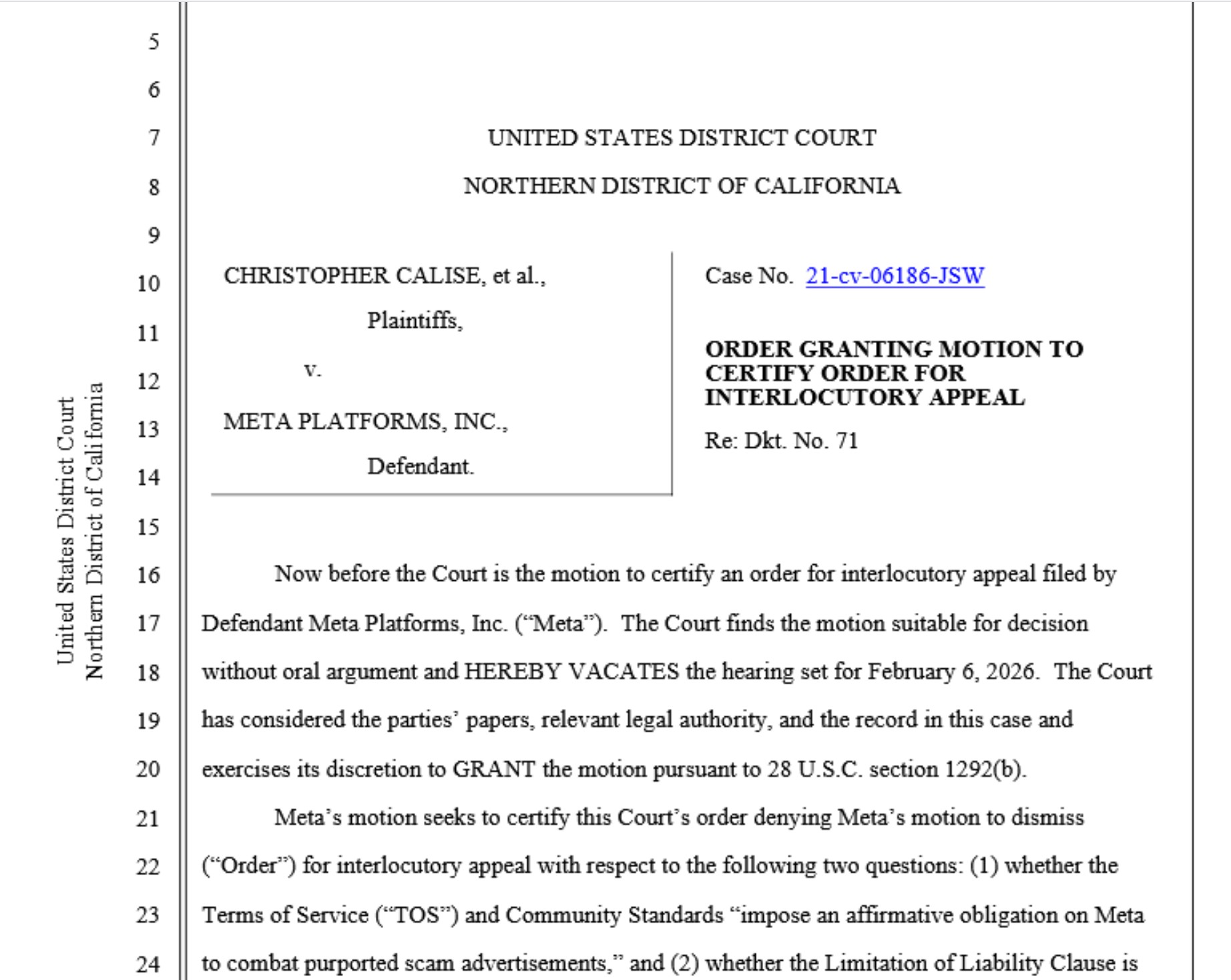

We are now in talks with many victims across Europe as we prepare a collective action, and Payvision is the clearest proof that the EU’s ADR architecture fails fraud victims.

What the public record already establishes about Payvision

Wind-down and exit: ING announced the phase-out of Payvision’s PSP/acquiring business in October 2021, targeting completion by Q2 2022.

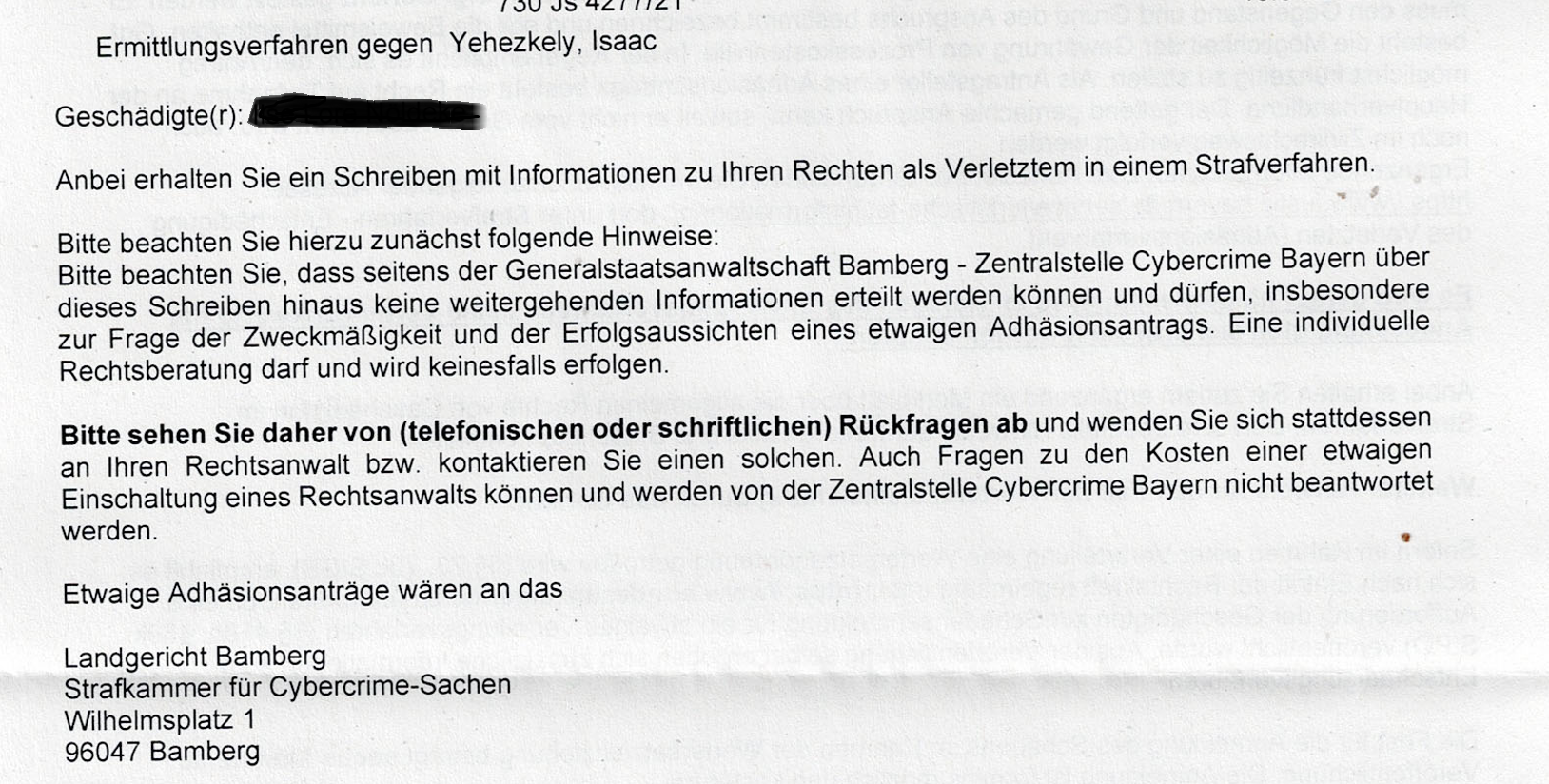

Criminal enforcement against ex-directors: On 5 April 2024 the Dutch Public Prosecution Service imposed fines of €150,000 and €180,000 on two former Payvision directors for years of structural Wwft (AML) violations.

These facts alone expose a gatekeeper failure at the acquiring layer during the relevant period—exactly the failure that multiplies consumer harm in cross-border investment and impersonation scams.

Same scams, different outcomes: UK vs EU

There are tens of thousands of Barak/Lenhoff victims in the United Kingdom, more than in any other country. Based on our research, Payvision processed most of the card payments, both credit and debit. Over recent months our discussions with victims revealed a clear pattern: across Europe (including UK), issuing banks almost uniformly rejected chargebacks, often on pretextual grounds. From that point the experiences diverged. UK victims who escalated their cases to the Financial Ombudsman Service typically obtained refunds together with interest, even though the process often took years. By contrast, victims in continental Europe report only negative outcomes from their national financial ombudsmen.

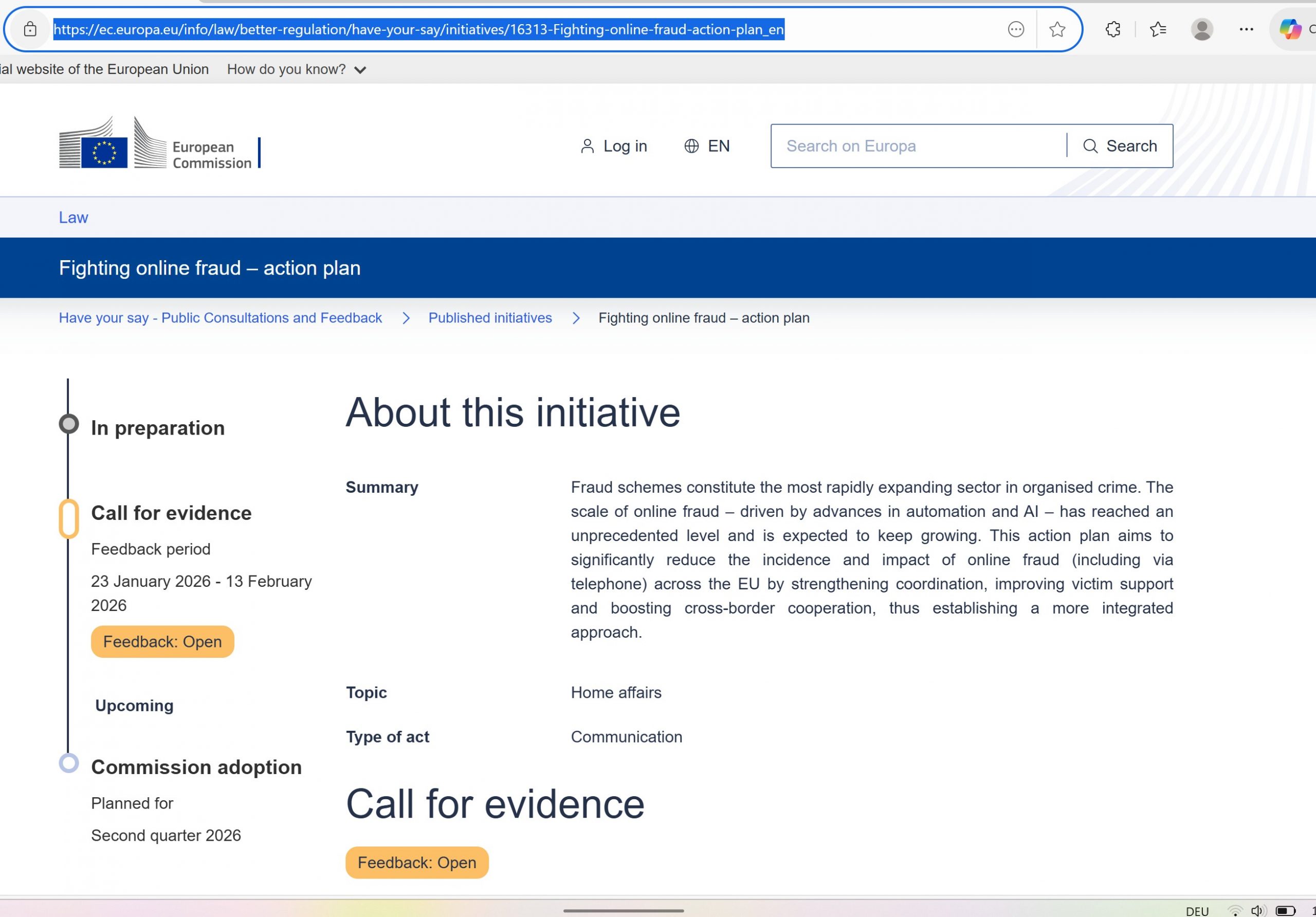

As previously discussed, the ADR regime established at EU level (Directive 2013/11/EU) falls short of affording effective and binding consumer protection and the proposed ADR is not set to improve the situation:

United Kingdom (works): The Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) can make binding awards once the consumer accepts the final decision; firms must comply. In practice, this has enabled refunds for victims in card and payment disputes that banks mishandled.

In parallel, the Payment Systems Regulator introduced mandatory reimbursement for APP fraud in Faster Payments from 7 October 2024 (with an £85,000 cap). This regime pushes consistent victim outcomes and forces PSPs to use their prevention levers.

European Union (doesn’t work): The ADR Directive (2013/11/EU) provides access but leaves key elements—like binding effect and participation duty—to Member States. The Commission’s 2023 evaluation flags weak cross-border performance and limited uptake; reforms so far are incremental.

Bottom line: UK victims get enforceable decisions and a statutory reimbursement backstop; EU victims meet soft-law networks and non-binding outcomes. Payvision-type fact patterns make this gap painfully visible.

Why this is unjust—and avoidable

Victims who used identical sales funnels and acquiring rails should not face opposite outcomes depending on whether they live in Manchester or Munich. The law already recognises PSPs and acquirers as gatekeepers; when that gatekeeping breaks (as Dutch prosecutors concluded happened at Payvision during 2016–2020), the remedial path must not depend on a firm’s willingness to “voluntarily” follow an ADR recommendation.

What policymakers should fix—fast

Scammers do not respect borders, and neither do payment service providers. Passporting enables cross-border operations. Why should the losses fall on victims?

We call for the establishment of an EU-wide, binding financial ombudsman, mirroring the FOS model, with decisions enforceable once accepted by the consumer. The Payvision case demonstrates the harm caused by Europe’s ineffective ADR framework.