Disclaimer: We have just started to dig into this topic, so this article is for public‑interest information and advocacy discussion. It summarises complex issues and may become outdated as cases and enforcement evolve.

Why this matters: scam ads are not “just content”

When a scam appears in a social feed as an advertisement, a paid placement, victims often feel (with good reason) that the platform is not merely “hosting someone’s speech.” It is selling a distribution product that can result in fraud in front of millions.

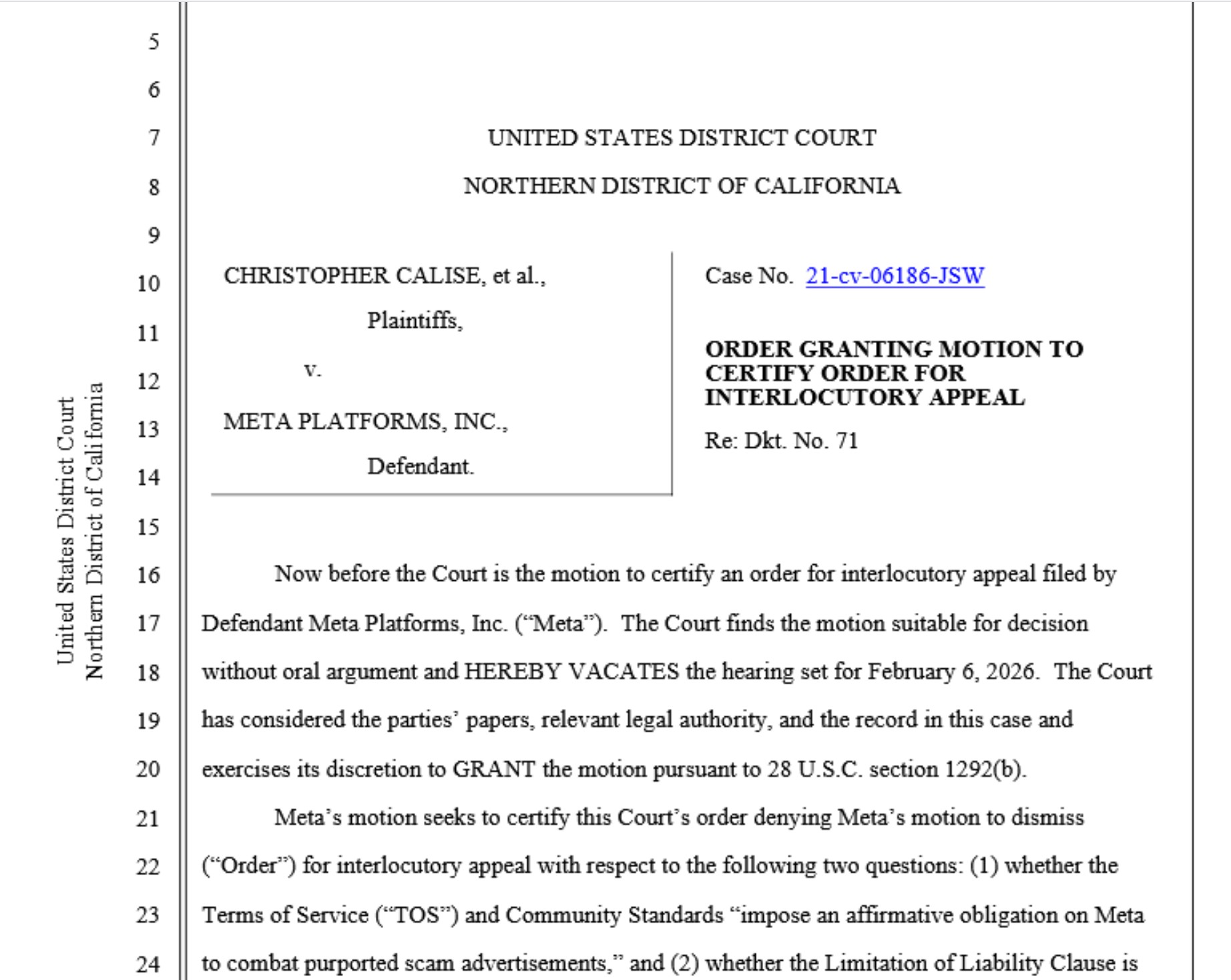

That’s why the US case Calise v Meta caught our attention: the courts have treated Meta’s own platform rules, set out in its Terms of Service and Community Standards, as potentially enforceable promises, at least at the pleading stage, rather than mere aspirational statements (district court order on remand: 22 September 2025, following a partial Ninth Circuit reversal on Section 230). As of 8 January 2026, that ruling has been certified for interlocutory appeal, and Meta may seek Ninth Circuit review on issues of enforceability and unconscionability.

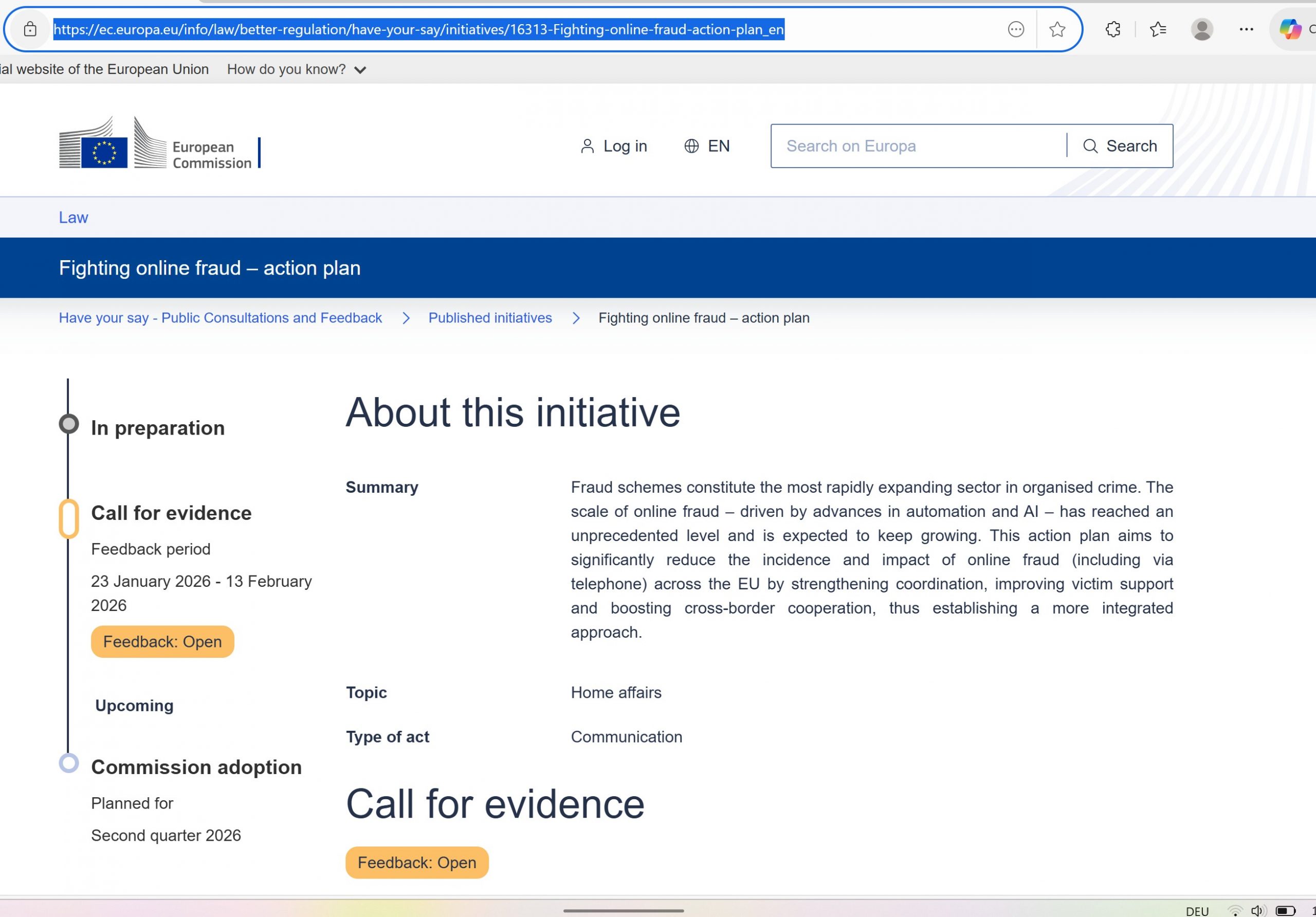

But Europe is different. Legal action in Europe requires analysis of the following directives and regulations:

DSA (Digital Services Act) process duties (especially Notice‑and‑Action)

DSA compensation concept (Article 54)

GDPR limits on “we’ll legalise it by writing it into the Terms”

Irish consumer law (unfair terms, transparency, etc.)

And—if you want group redress—Ireland’s Representative Actions framework (Qualified Entities)

This article summarises our thoughts as of today.

Part 1 — The US: What happened in Calise v Meta (and what the court actually allowed)

In Calise v Meta (Northern District of California), scam victims sued Meta (Facebook). They alleged they were defrauded through scam ads / deceptive content and argued that Facebook’s Terms of Service (ToS) and Community Standards (CS) contained specific anti‑scam commitments (e.g., to take “appropriate action” when it detects misuse).

The court allowed the plaintiffs to proceed on contract‑based claims, essentially treating Meta’s written commitments as potentially enforceable obligations, at least at the pleading stage. It also allowed a claim for breach of the covenant of good faith and fair dealing (a doctrine that has stronger footing in some US states than in Europe/Ireland).

A tort‑style claim framed as negligent failure to warn was dismissed, based largely on the idea that the plaintiffs sought recovery for pure financial loss and that this sort of tort theory was not viable under the relevant “economic loss” doctrine in the circumstances.

Why Calise matters for Europe (even though Europe isn’t the US)

The “big idea” in Calise is promise‑based accountability:

If a platform makes specific safety / anti‑fraud commitments, it shouldn’t be able to hide behind broad “third‑party conduct” disclaimers when it allegedly fails to implement those commitments.

Europe can reach a similar reasoning not only through contracts but via statutory duties to enforce platform terms as set out in the DSA.

Part 2 — Europe’s engine: DSA + GDPR + national private law

Europe starts with the DSA: the platform process rulebook

A) The DSA hosting liability baseline is conditional (Article 6)

The DSA’s hosting liability rule says a hosting provider is not liable for illegal content stored at a user’s request if it:

does not have actual knowledge of illegal activity/content (and for damages, is not aware of facts/circumstances making illegality apparent), or

upon obtaining knowledge/awareness, acts expeditiously to remove/disable access to the illegal content.

That “knowledge → expeditious action” hinge is where scam‑victim strategy often lives.

Note: Article 6 is a conditional liability exemption; whether liability exists (and on what cause of action) still depends on applicable Union/national law, Article 6 mainly frames when the hosting defence is available.

B) Europe does not impose “monitor everything” (Article 8)

Platforms are not subject to a general obligation to monitor everything or to actively seek facts indicating illegality.

This matters because it’s one reason platforms often say:

“We can’t technically catch all scams in advance.”

Europe’s response is: Okay, but you must run a functional system for after you’re told, and you must manage systemic risks (especially if you’re a VLOP).

C) DSA Notice‑and‑Action is the victims’ evidence spine (Article 16)

Article 16 requires hosting services to provide easy, user‑friendly electronic mechanisms to notify them of specific content items alleged to be illegal.

A proper DSA notice should include (minimum):

a substantiated explanation of why the content is illegal

the exact electronic location (e.g., exact URL(s), and additional identifiers where needed)

the notifier’s name and email (with narrow exceptions)

a “bona fide belief” statement that the allegations are accurate and complete.

Two features are crucial for scam cases:

A detailed notice can trigger “actual knowledge”

A notice is considered to give rise to actual knowledge/awareness for Article 6 if it allows a diligent provider to identify illegality without a detailed legal examination.The platform must acknowledge and decide.

If you include contact info, the provider must send a confirmation of receipt, and must notify you of its decision and available redress options—without undue delay.

Translation into practical advocacy:

A well‑structured Article‑16 notice turns “I reported it” into documented knowledge, and it forces the platform into a decision trail.

D) Europe also makes ToS enforcement itself a legal duty (Article 14)

This is where Europe can echo the “promise‑based” idea of Calise, but through statute.

The DSA requires intermediary services to:

include restrictions and content‑moderation tools/policies in their terms of service in clear language, publicly available .

and apply/enforce those restrictions diligently, objectively, and proportionately, with due regard to fundamental rights.

E) For very large online platforms (VLOPs): “systemic risk” duties (Article 34)

For VLOPs, the DSA goes further: they must identify, analyse and assess systemic risks stemming from the design/functioning of the service and its systems (including algorithmic systems). That risk assessment must include, among other things, the dissemination of illegal content.

That doesn’t mean “Meta knows every scam ad.” It does mean: scam ads are not a surprise edge case, they are a predictable systemic risk that must be assessed and mitigated.

F) Compensation is explicitly “on the table” (Article 54)

The DSA states that recipients of the service have the right to seek, under Union and national law, compensation for damage or loss due to a provider’s infringement of DSA obligations.

But the DSA still stops short of a clear-cut liability rule for scam-ad victims: it recognises a right to seek compensation (Article 54), yet leaves the actual liability standard and route to damages largely to national private law rather than spelling out a platform-liability test for monetised scam advertising.

For background on the scale/economics of scam ads and why victims still struggle under the current framework, see Meta’s Scam Ad Empire – and Why the Digital Services Act Still Fails Europe’s Victims.

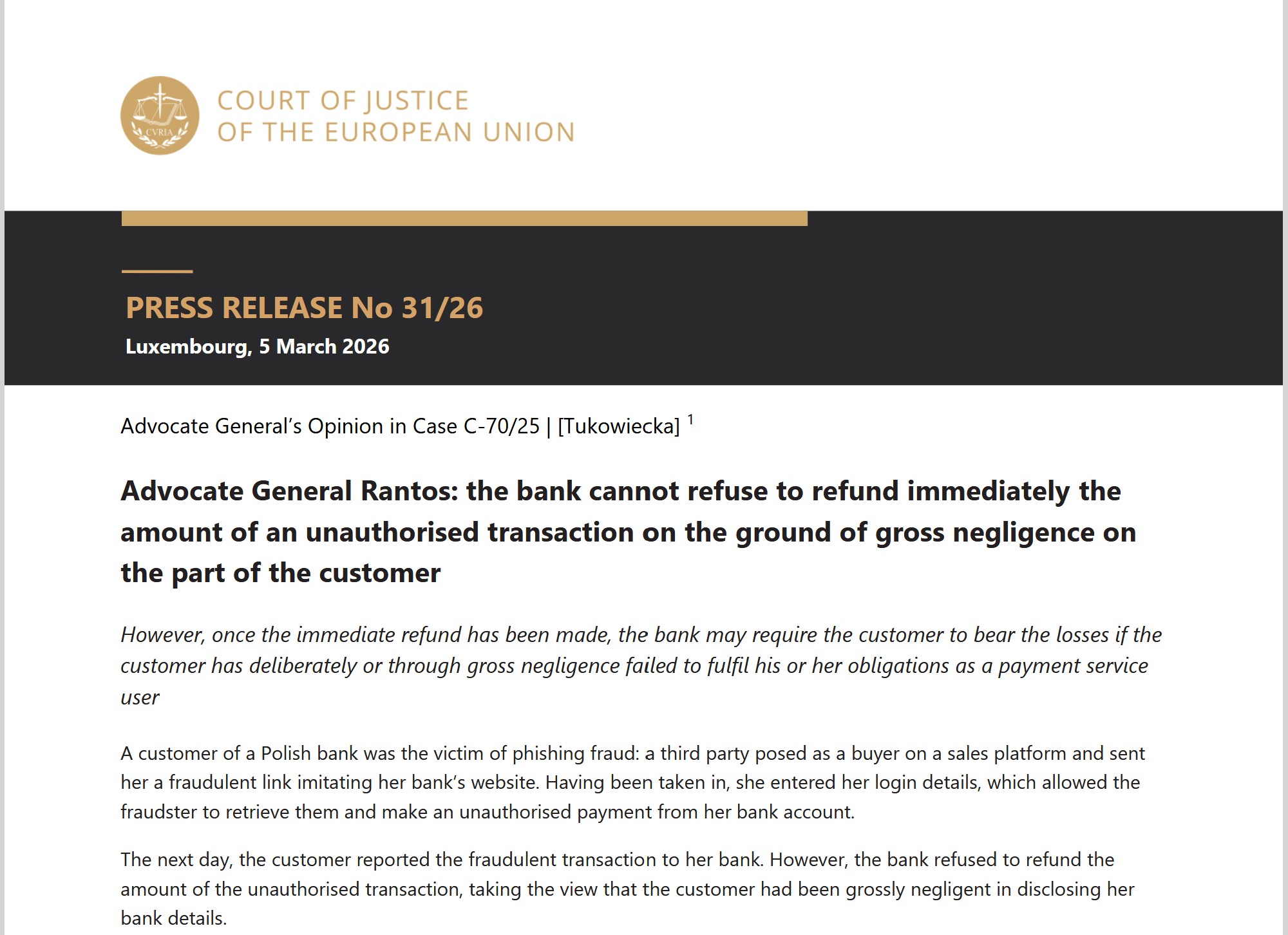

Part 2 — Irish law “support beams”: unfair terms and consumer protections (especially for liability caps)

Irish private law matters for remedies, especially when platforms point to sweeping liability caps in ToS.

The CCPC’s (Irish Competition and Consumer Protection Commission) guidance also captures a key practical point: an unfair term is not binding, but the rest of the contract can remain in force.

Marketplace‑style claims: note DSA Article 6(3)

DSA Article 6(3) includes a consumer‑protection carve‑out for certain online platforms that allow consumers to conclude distance contracts with traders, where the platform’s presentation could lead an average consumer to believe the platform (or someone under its control) provides the product/service.

This is not automatically a “Meta is liable for every Marketplace scam.” But it is a reminder that consumer protection logic is built into the DSA hosting framework in specific contexts.

The DSA is within the scope of the EU Representative Actions framework because the DSA adds itself to Annex I of Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (DSA Article 90), meaning DSA infringements can, in principle, be pleaded within representative-action architectures (subject to national procedure/standing rules).

Part 3: How could a litigation path look like?

A) Litigation strategy: use DSA as evidence‑building lever

Step 1: Document with Article‑16 notices. Send detailed, compliant notices for specific scam ads (exact URLs, illegality explanation). The response trail proves (or disproves) knowledge and expeditious action. Multiple ignored notices build systemic‑risk evidence under Article 34.

Step 2: Target ToS enforcement via Article 14. Argue that Meta’s anti‑scam commitments (e.g., “appropriate action”) must be applied diligently. Cross‑reference Calise: platforms cannot disclaim enforceable promises they publicise.

Step 3: Irish representative actions for scale. For scale in Ireland, a Qualified Entity like EFRI can bring a representative action for in-scope consumer-rights infringements; affected consumers typically opt in for redress measures.

EFRI`s next steps

We are tracking Calise developments and are still digging into the European legal possibilities. But we have already started compiling victim datasets on this topic and are preparing model Article‑16 templates.