The collapse of Wirecard exposed one of the worst regulatory failures in modern European financial history. For years, Germany’s financial watchdog BaFin ignored whistleblowers, dismissed detailed press investigations, attacked journalists instead of fraudsters, and even imposed a short-selling ban that stabilised the share price of what was, in fact, a criminal enterprise.

When Wirecard finally imploded in June 2020, billions were gone and tens of thousands of investors were wiped out. Many believed BaFin would finally face legal consequences.

Instead, the opposite happened: every single lawsuit against BaFin failed. German courts at all levels have declared that BaFin bears no legal responsibility for investors’ losses – not a single cent.

It is more than a failure. It is shameless.

The Courts Closed Ranks to Protect the Regulator

In the aftermath of the scandal, investors brought a series of lawsuits against BaFin. They believed — one would assume correctly — that the watchdog had helped enable Wirecard’s fraud through a mixture of incompetence, misplaced loyalty, and active hostility toward those sounding the alarm.

The German judiciary, however, delivered a perfectly consistent verdict:

BaFin owes no duty to individual investors.

BaFin’s actions were “within its discretion.”

BaFin cannot be held liable — no matter how catastrophic the results.

Lower Courts: No Duty, No Fault, No Causation

The first investor actions against BaFin were filed before the Regional Court (Landgericht) Frankfurt am Main. In several parallel cases (including LG Frankfurt/Main, judgment of 19 January 2022, 2-04 O 561/20), investors argued that BaFin had ignored signals in the market, failed to intervene despite massive red flags, and misled the public through its 2019 short-selling ban on Wirecard shares.

The court rejected all claims. In its press release “Abweisung von Klagen der Wirecard-Anleger gegen die BaFin”, the Hessian judiciary summarised the core reasoning: BaFin’s statutory tasks under § 4 FinDAG are exercised “im öffentlichen Interesse” – in the public interest – and not for the benefit of individual investors. Therefore, its duties are not “drittschützend”; they do not create a legally protected duty of care towards shareholders.

Even if BaFin had made serious mistakes, the court held, these mistakes did not amount to a breach of an individual duty of care. On top of that, investors were told they had not proven causation. They could not show that, had BaFin acted differently, they would not have bought Wirecard shares.

With these 2022 Frankfurt judgments, the pattern was set: BaFin may fail, but there is no liability.

Appeal Level: OLG Frankfurt, LG Trier, OLG Stuttgart

On appeal, the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt (OLG Frankfurt) confirmed this approach. In OLG Frankfurt, judgment of 6 February 2023, 1 U 173/22, the court explicitly held that BaFin is not liable to investors for alleged supervisory failures in the Wirecard case. The official press release “Keine Haftung der BaFin gegenüber Anlegern im Zusammenhang mit dem Wirecard-Skandal” and subsequent commentary underline the key point: BaFin’s tasks serve market integrity as a whole, not individual investors, and there is no actionable duty toward a specific shareholder.

Further support for this line came from LG Trier, judgment of 24/25 April 2024, 11 O 236/23, which also dismissed a Wirecard investor’s claim against BaFin. The decision is discussed in detail by Prof. Hervé Edelmann in his article ‘Keine Haftung der BaFin im Zusammenhang mit dem Wirecard-Skandal’, BKR 2024, 701 ff.

The Higher Regional Court of Stuttgart (OLG Stuttgart) then confirmed the same reasoning for its district. In OLG Stuttgart, judgment of 18 December 2024, 4 U 94/24, the court found that BaFin’s decision to impose the 2019 short-selling ban on Wirecard was, at least from an ex-ante perspective, “defensible” – and therefore no actionable breach of duty. Local press reports (such as Stuttgarter Nachrichten under the headline “Kein Schadenersatz für Wirecard-Anleger”) summarise that the court denied both an Amtspflichtverletzung and any causal link between BaFin’s behaviour and investor losses.

Each of these courts cited the same building blocks: no individual duty, wide discretion for the supervisor, and impossibly strict causation requirements. The result: no liability anywhere in the system.

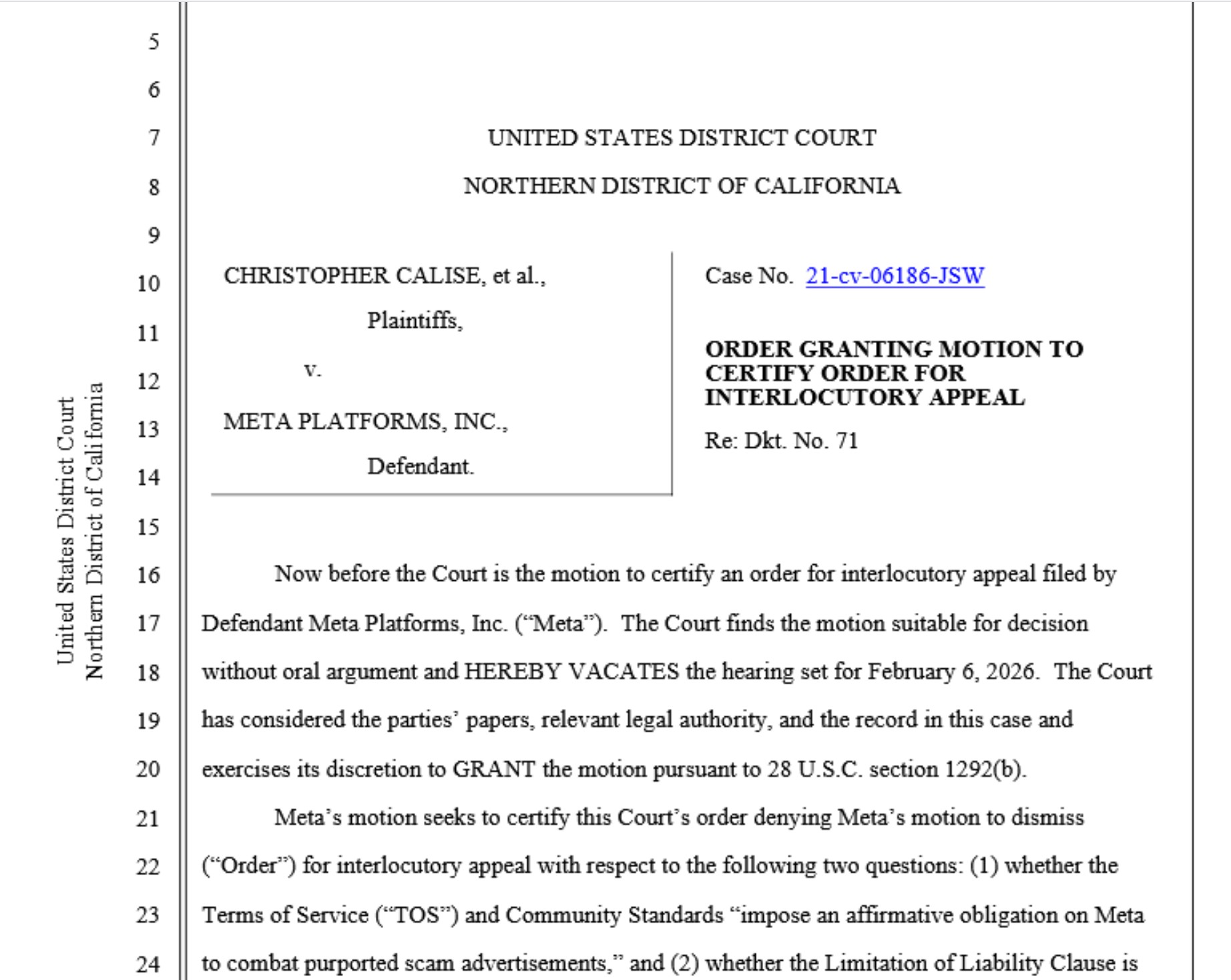

The Key Turning Point: BGH, 10 January 2024 – III ZR 57/23

The decisive moment came at the Federal Court of Justice (BGH). In BGH, decision of 10 January 2024 – III ZR 57/23, the highest civil court rejected a Wirecard investor couple’s claim for damages against the German state based on BaFin’s alleged supervisory failures.

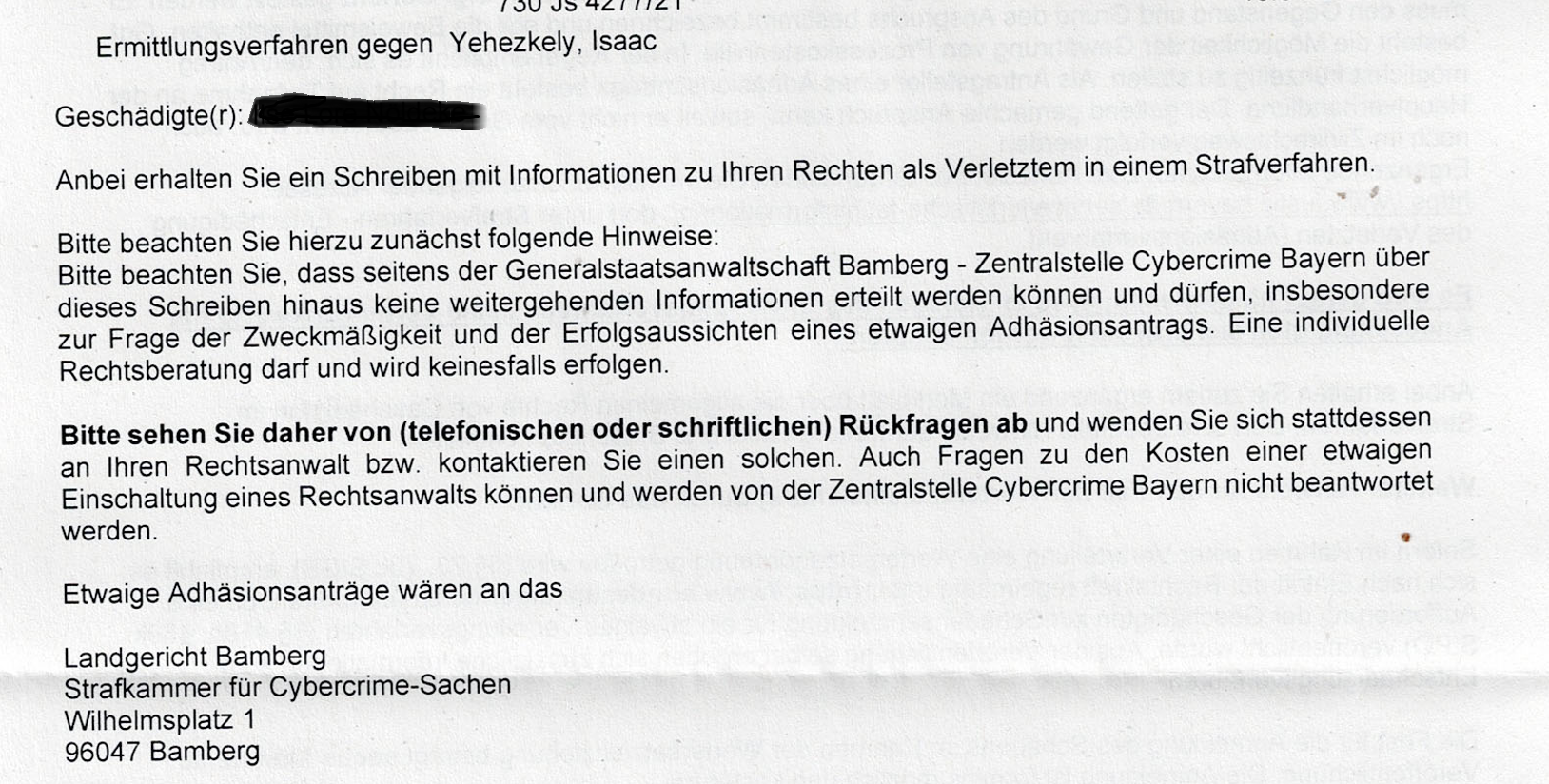

The case concerned both a classic German state liability claim (Amtshaftung under § 839 BGB in conjunction with Art. 34 GG) and an EU-law based state liability claim. The investors argued that BaFin had, among other things, failed to take Bilanzkontrolle (accounting enforcement) into its own hands and had instead shielded Wirecard by imposing the short-selling ban and filing a criminal complaint against Financial Times journalists.

The BGH did something highly significant:

It avoided a clear statement on whether BaFin’s duties are ever “drittschützend” for investors.

Instead, it concluded that BaFin’s actions were, from an ex-ante perspective, at least “nicht zu beanstanden” – not objectionable. If a measure is legally “defensible”, there can be no actionable breach of duty.

For the EU-law claim, the court found no “hinreichend qualifizierten Verstoß” – no sufficiently serious breach required for EU state liability.

In plain language: unless BaFin acts in a way that is not just wrong but utterly irrational or abusive, it will not be liable.

This single judgment effectively constitutionalised BaFin’s immunity. Commentators already describe III ZR 57/23 as the case that “pulled the plug” on any realistic hope for investor compensation via state liability.

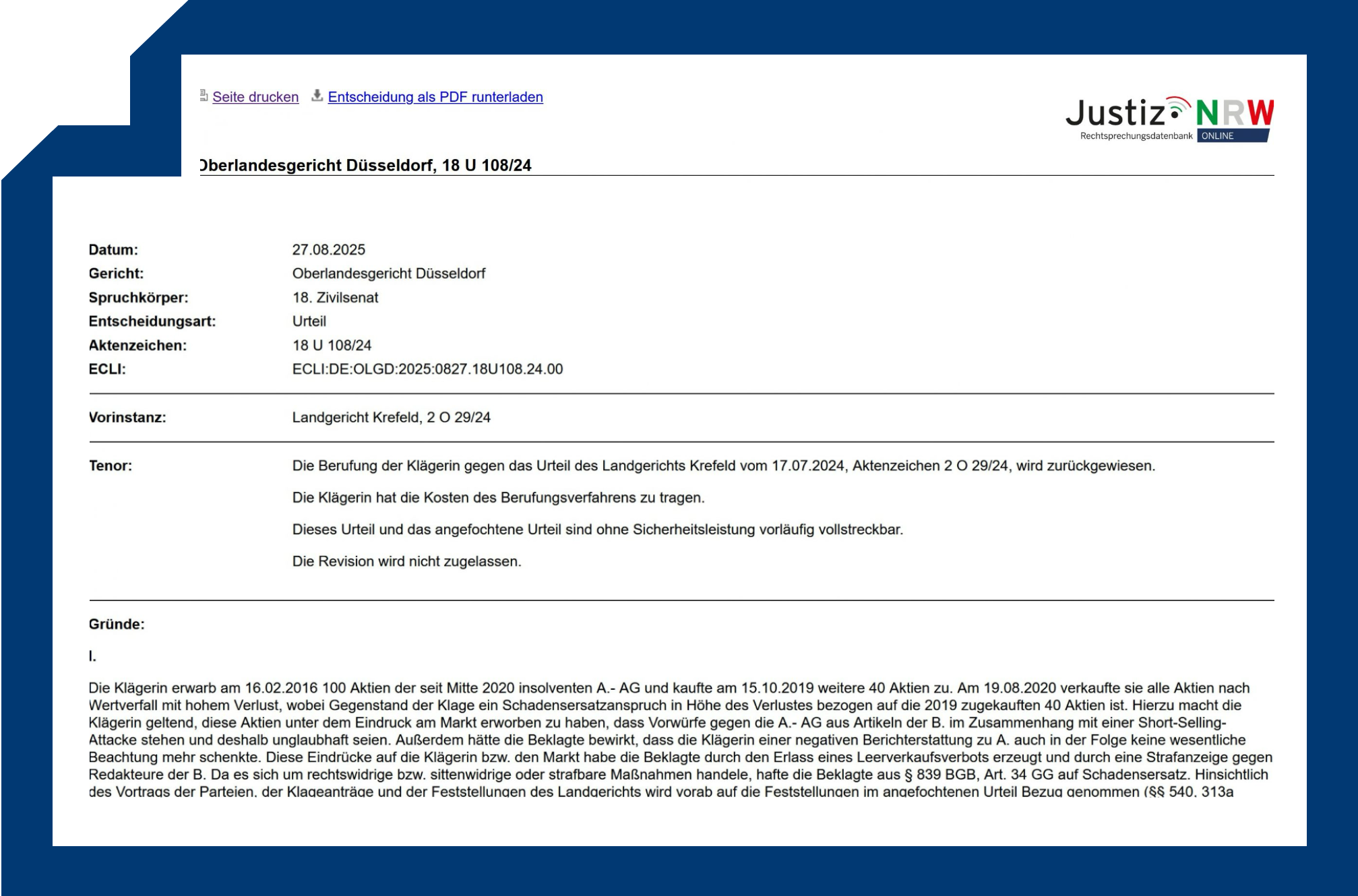

OLG Düsseldorf 2025: The Symbolic Last Word

The most recent high-profile decision came from the Higher Regional Court of Düsseldorf. On 27 August 2025, the court decided in I-18 U 108/24 to reject the claim of a Wirecard shareholder from Krefeld. She argued that BaFin’s short-selling ban and its criminal complaint against Financial Times journalists had signalled to her that the allegations against Wirecard were unfounded; under that impression, she bought additional shares which later became worthless.

The Düsseldorf court followed the BGH line almost mechanically:

It saw no culpable breach of duty, stressing that both the short-selling ban and the criminal complaint were “reasonable” in light of the situation at the time.

It also denied causation: even if BaFin’s actions influenced market perception, the plaintiff could not meet the strict standard of proving that she would have acted differently under a hypothetical alternative supervisory response.

The official press release of the OLG Düsseldorf (“Kein Schadensersatzanspruch einer Wirecard-Aktionärin gegen die BaFin”, Pressemitteilung Nr. 26/2025) makes clear that this judgment is fully aligned with the BGH’s approach in III ZR 57/23.

The Structural Logic: How the Law Protects BaFin, Not Investors

If you line up LG Frankfurt (2022), OLG Frankfurt (2023), BGH III ZR 57/23 (2024), LG Trier (2024), OLG Stuttgart (2024) and OLG Düsseldorf (2025), a very clear pattern emerges:

No individual duty (no “Drittschutz”)

Courts insist that BaFin’s role is to protect the financial system and “public interest”, not individual investors. This interpretation of § 4 FinDAG means that even dramatic supervisory failures do not translate into compensable rights for shareholders.Extremely broad regulatory discretion

Supervisory decisions such as the short-selling ban and the criminal complaint against journalists are treated as legitimate exercises of discretion as long as they are not obviously absurd. From that perspective, BaFin’s behaviour in the Wirecard scandal is recharacterised as “at least defensible”.Causation pushed into the realm of fiction

Investors are required to prove that, had BaFin acted properly, they would certainly have behaved differently. In a complex information environment with analysts, media, corporate statements and hype, this is almost impossible. Courts consistently use this argument to deny a legally relevant causal connection.EU-law state liability neutralised

Even where European rules require effective supervision, the BGH and lower courts deny any “sufficiently serious” breach. This blocks the only theoretical path that might have forced Germany to compensate victims for supervisory failure.

The combined effect is a system in which BaFin is practically immune, even in the face of a scandal of Wirecard’s magnitude.

Political Condemnation Without Legal Consequences

What makes this situation even more perverse is the contrast between the political and legal responses.

Politically, the Wirecard Inquiry Committee of the German Bundestag documented a failure “auf ganzer Linie” across all control institutions, including BaFin. ESMA’s fast-track report and follow-up work identified serious deficiencies in German accounting enforcement and supervision structures.

The reaction:

BaFin’s senior leadership was removed.

The Finanzmarktintegritätsstärkungsgesetz (FISG) was passed to reform supervision and tighten auditor oversight.

But none of this produced what victims actually needed: compensation and accountability. There was no damages fund, no recognition of state responsibility, and no personal liability for decision-makers who had backed the wrong side for years.

The German state restructured its watchdog. It did not repair the damage it had allowed to happen.

It’s not just that BaFin escaped liability.

The way it escaped liability has a very concrete price: retail investors in Germany simply don’t trust the system anymore – and they’re increasingly behaving as if they are on their own.

Let me break down what we can actually see in the data and what follows from it.

Loss of Trust is piling up

Right after Wirecard collapsed, a representative survey quoted by t-online found that 55.4% of Germans said their trust in “Finanzplatz Deutschland” had decreased or rather decreased because of the Wirecard scandal. Only 1.6% said it had increased.

This wasn’t just abstract disappointment. It came on top of the insider-trading scandal within BaFin itself – nearly 500 Wirecard-related trades by BaFin staff were later identified, forcing the authority to tighten its internal rules for private financial dealings.

So from the retail investor’s perspective, the picture was:

the listed company was a fraud,

the auditor failed,

the supervisor failed,

and parts of the supervisor’s staff were trading the stock privately.

Once courts then declared that BaFin bears no legal responsibility at all for this chain of failure, the intuitive message to small investors is finally: “You can’t rely on anyone. If something goes wrong, you carry 100% of the loss.”

EFRI's take

From a consumer-protection perspective, BaFin’s non-liability in Wirecard is not just a legal scandal; it’s a trust-erosion mechanism.

Retail investors learn three brutal lessons:

A DAX listing, a Big-Four audit and BaFin supervision do not mean anyone is actually protecting them.

When the system collapses, nobody in the system pays.

If they want protection, they have to create it themselves – by diversification, scepticism and avoiding anything that depends on the German supervisory “brand”.