Across Europe, fraud is not only on the rise – it is also being systematically concealed. In the UK, only around 13% of fraud against individuals is reported. In Canada, authorities estimate that only 5–10% of scams ever reach the official system, while the real annual loss is believed to be in the double-digit billions. If this is the situation in well-organised OECD countries, then Europe’s true fraud landscape is not merely underestimated – it is almost entirely invisible.

This is not primarily a problem of “awareness”. It is a problem of how the reporting system is designed. In practice, it teaches victims to stay silent.

Victims do not report because the system makes it irrational to speak up

The standard story is that victims are too ashamed or embarrassed to report. Stigma is real, but it cannot explain underreporting on the scale of 80–90%. The real drivers are structural:

Reporting feels pointless

Victims of cross-border investment scams, crypto fraud or APP fraud very quickly learn the same lesson:

cases are misunderstood,

proceedings are quietly dropped,

there is no meaningful prospect of refund.

If the expected outcome of reporting is “nothing happens, and I stay with 100% of the loss”, not reporting becomes a rational choice.

Institutional victim blaming

Banks, payment service providers and crypto exchanges still push the same defensive narrative:

“You authorised the transfer – it’s your own responsibility.”

This message is devastating. It shifts the focus away from the professional intermediaries who processed and profited from the transaction, and pins the blame entirely on the victim. Word spreads quickly: “If you report, they just tell you it’s your fault.”

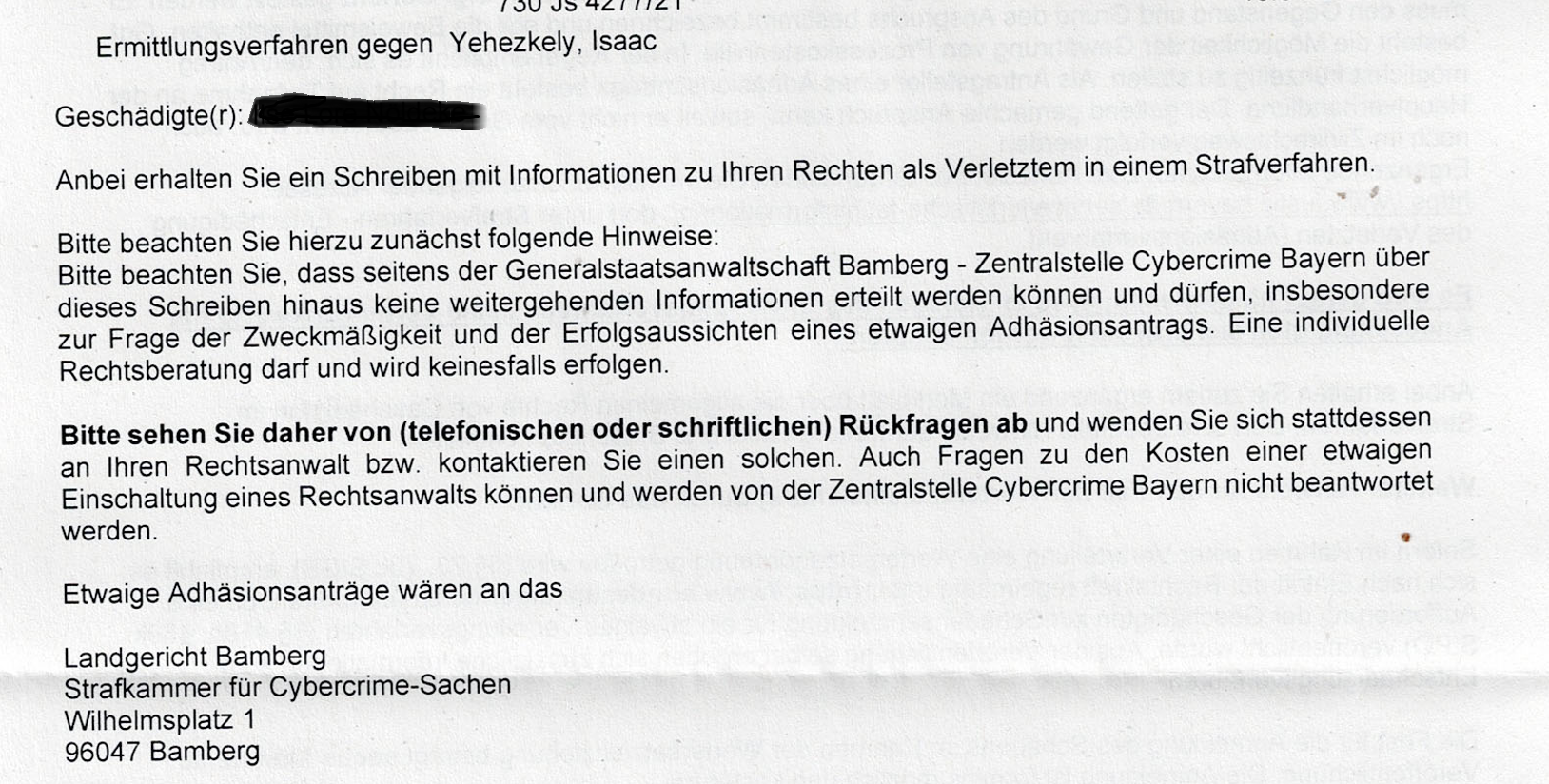

Systemic gaslighting: silence after reporting

Even worse is what happens to those who do overcome their fear and report.

Victims file detailed reports, provide documents, sometimes testify. Investigations are formally opened. Case numbers are assigned. And then:

nothing.

No regular updates.

No explanation of what is being done.

No information about whether charges were filed, whether the case was closed, whether assets were seized, whether other victims were identified.

Victims are left to chase prosecutors and police for basic status information – and are often told nothing beyond “ongoing investigation” or “we will contact you if necessary”. Months or years later, they discover by accident that their case has been quietly closed or merged into some abstract “complex investigation”.

This silence is a form of institutional gaslighting:

The system claims to “take fraud seriously”,

but treats victims as if they were irrelevant once the report is on file.

It signals: “Your role is to provide information and then disappear.”

After this experience, victims tell others: “Reporting was a complete waste of time. Nobody told me anything, nothing came out of it.” That message kills future reporting more effectively than any scammer ever could.

No clean reporting pathway

Europe offers hotlines, email addresses, police desks, web forms and consumer portals – but no clear, joined-up pathway from reporting to investigation, intelligence and redress. Each country has its own patchwork, and none of them are built around the reality of large-scale online investment fraud.

The result is predictable: many victims simply give up before they even start – and those who tried once rarely try again.

Austria: A reporting landscape that manufactures silence

Austria is a textbook example of how a system can look “modern” on paper while still producing massive underreporting.

There is a cybercrime reporting address at the Federal Criminal Police Office.

But it exists mainly to collect hints and suspicions – it cannot take formal criminal complaints.There is a “Cybercrime Helpline”, which provides advice and basic information.

But again: it cannot take criminal complaints.BUT there is a NO online reporting tool for reporting online fraud incidents.

For a real online fraud case, the kind of case EFRI deals with, the victim is told to appear in person at the local police station, explain an intricate international fraud to a non-specialised officer, and hope that the report is recorded correctly and not trivialised as “just a civil matter”. And also hoping that the neighbours are not at home when the police visit the victim for more questions.

And once the complaint is filed? In most cases there is no structured case tracking, no proactive updates, no transparent explanation of decisions. Victims must constantly ask what is happening – and often they receive nothing but silence.

For many, this is the end of the road. Elderly couples, people in rural areas, victims already traumatised by massive losses simply cannot face this process a second time. The system does not support reporting – it filters it out and then erases those who went through with it.

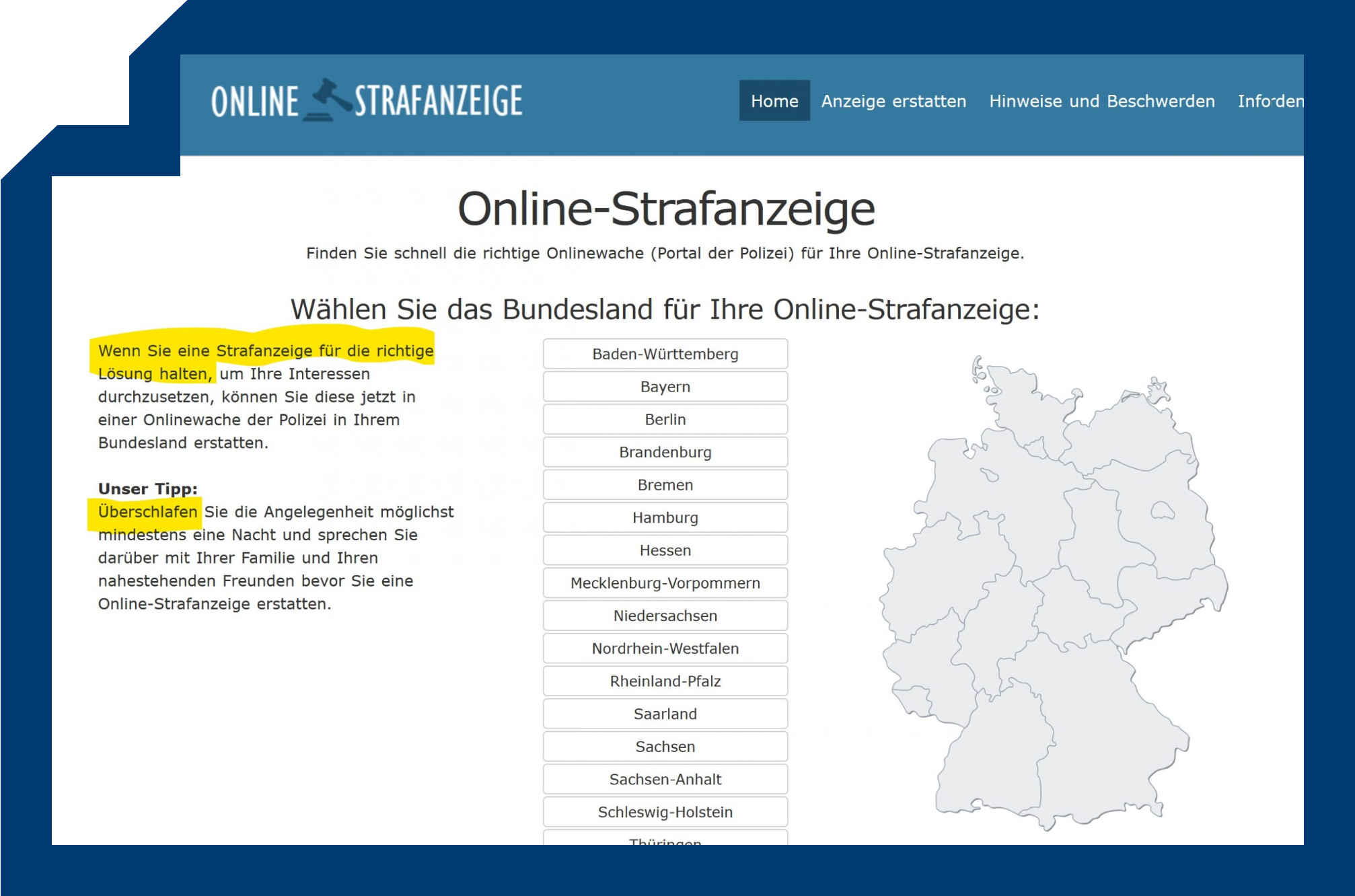

Germany: Online reporting that intimidates instead of protecting

Germany’s Online-Strafanzeige Portale appear to be a step forward: citizens can file criminal complaints online, including those related to internet fraud. But the way these portals are framed often has the opposite effect for insecure victims.

Before submitting a report, victims are confronted with prominent legal warnings:

Pretending a criminal offence

False accusation

Assisting an offender

Obstruction of justice

These warnings are legally correct and understandable from an enforcement perspective. But for a victim who already feels foolish, guilty and unsure whether what happened is “really” a criminal offence, this legal framing is intimidating. The advice to contact a lawyer before filing a complaint often results in additional costs and, in many cases, a loss for online victims.

The message that comes across is:

“If you describe this wrong, you might be the one in trouble.”

Many will simply close the browser and walk away.

And even for those who submit the report, the pattern is familiar: an automatic confirmation, then silence. No clear communication, no timeline, no transparent outcome. Once again, the victim disappears into a black box

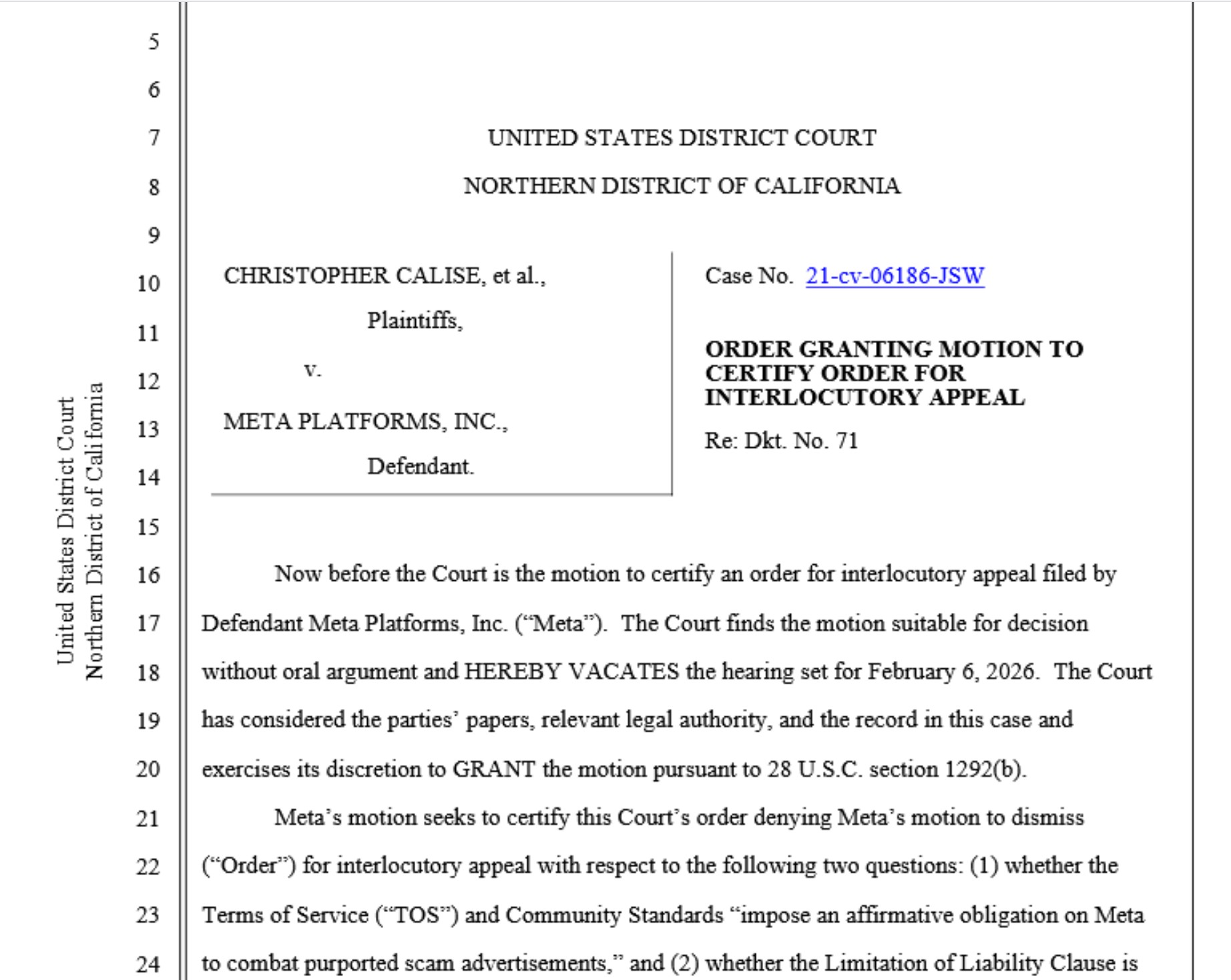

Europe’s blind spot: perfect conditions for fraud and for negligent intermediaries

Underreporting on the scale of 80–90% is not a side issue. It is the foundation on which today’s fraud economy rests.

When victims do not report, regulators stay blind.

When regulators stay blind, criminal networks scale without resistance.

When criminal networks scale, platforms, banks and PSPs keep earning fees – with almost no risk of enforcement.

Europe has:

- no EU-wide central hub for consumer fraud reporting,

- the obligation for banks and PSPs to send structured fraud data into a shared system is still at the beginning.

- no obligation for social media and crypto exchanges to send structured fraud data into a shared system exists.

no European framework for refund and redress in APP fraud scenarios,

and no enforceable obligation to keep victims properly informed about the progress and outcome of their cases.

The message to the market is clear:

fraud is tolerated as long as it stays statistically invisible, procedurally opaque and financially externalised onto the victims.

What needs to change – concretely

If Europe is serious about tackling fraud, it has to address underreporting at the root. That means rebuilding the system around victims, not institutions.

EFRI calls for:

A single EU-level fraud reporting and intelligence hub

A central authority that receives, standardises and analyses fraud reports from victims and from financial intermediaries – cross-border by design.Mandatory fraud reporting by crypto exchanges and social-media companies

Fraud incidents and suspicious patterns must be reported as systematically as AML suspicions. Fraud data cannot remain a private risk-management secret.A shared liability framework for authorised push payment (APP) fraud, as proposed by us.

Victims should not bear 100% of the loss when financial intermediaries and platforms have enabled and profited from the crime.Simple, digital and specialised reporting channels in every member state

A 75-year-old victim should not have to explain fake crypto platforms and chargeback codes in a rural police station. Online tools must be tailored to complex online fraud and linked directly to specialised units.Reporting environments that protect victims instead of scaring them

Legal warnings against malicious false reports must not be turned into psychological barriers for traumatised victims who are doing their best to describe what happened.No gaslighting of victims

Victims must be informed about the status of their case: whether it is being pursued, paused, closed, or merged into a larger investigation. Silence is not acceptable. It is a form of institutional gaslighting – and it destroys trust.