The revision of the EU Victims’ Rights Directive announced on 10 December 2025 is presented as a major step forward for crime victims in Europe, just like the new PSR/PSD3 package is sold as a breakthrough for payment users. But for online investment fraud victims, the reform is a missed opportunity: the final deal keeps the weak points that matter most in practice – especially on compensation and state responsibility.

Why the online fraud victims still lose

The original Commission proposal of 2023, later strengthened by the European Parliament, would have delivered two practical game‑changers:

Courts could no longer simply send victims to separate civil proceedings instead of deciding on compensation in the criminal case.

Member States would have been obliged to pay compensation awarded in criminal judgments directly to victims and then recover the money from offenders.

This would have been crucial in countries like Germany and Austria, where courts regularly use the option to refer victims to civil courts and where victims are left with unenforceable paper claims against insolvent or unknown offenders. In the final compromise, however, these core elements disappeared: state advance payments were reduced to an optional tool for violent intentional crimes only, the “escape clause” remained intact, legal aid stayed narrow and conditional, and no real enforcement mechanisms were added. Online fraud victims are therefore still in the same position: they may have rights on paper, but they continue to bear almost the entire financial risk when cases are dropped, offenders are not convicted, or convicted offenders have no assets

1. How the rules evolved – and why they disappoint again

The EU Victims’ Rights Directive 2012/29/EU was touted as the cornerstone of EU victims’ rights policy, providing all victims with information, support, protection, and access to justice, regardless of the crime or where in the EU it was committed.

In 2020 the European Commission admitted that the full potential of the Directive had not been reached and that implementation was “not satisfactory”, mainly because of incomplete and/or incorrect transposition by Member States. A 2023 briefing for the European Parliament repeats the same message and notes “numerous concerns over its practical implementation”, especially on access to information, support and protection – and even refers to ongoing infringement proceedings

The BeneVict project, covering 26 Member States, confirms this picture: many countries have now transposed the Directive on paper, but practical implementation remains inconsistent and victims still face barriers due to systemic shortcomings and poor coordination between authorities

For online fraud and cross‑border investment scam victims, the gap between EU law and reality is even wider: many cases are not treated as serious crime, cross‑border investigation and asset recovery remain rare, and the formal “right to a decision on compensation” is meaningless when the offender is insolvent, unknown, or located in a third country. Against this background, revising the Victims’ Rights Directive was a unique chance to turn paper rights into real compensation and enforcement – a chance largely missed.

2. What the Commission proposed in 2023: a real shift on compensation

In July 2023, the Commission tabled COM(2023) 424 – a proposal to amend the Victims’ Rights Directive. It aimed to: improve access to information and crime reporting, strengthen specialist support for vulnerable victims, ensure more effective participation in criminal proceedings, improve access to compensation, and align protection with victims’ actual needs.

Key elements of the proposal included:

EU‑wide 116 006 victims’ helpline and website

A universal victims’ telephone helpline 116 006 in all Member States.

A comprehensive website in major languages, accessible for persons with disabilities, using modern tools (chat, email).

Digital access and reporting

Obligations to enable victims to exercise their rights and report crime electronically, including victims in detention or with irregular status.

- Importantly for cross‑border cases: victims would not be blocked from using another Member State’s digital systems just because they are resident elsewhere, and national e‑systems would have to accept notified eID/e‑signature from other Member States

Stronger support and participation: A right to assistance at court and the right to challenge decisions affecting victims’ rights, regardless of their formal procedural status.

Most importantly, the proposal directly targeted Article 16 of the Directive, which regulates compensation from offenders. Under the 2012 text, Member States must ensure that victims can obtain a decision on compensation “in the course of criminal proceedings” – except where national law provides that such a decision shall be made in other legal proceedings. This last sentence is the infamous escape clause, allowing courts to push victims into civil proceedings that are slow, costly, and often hopeless in cross‑border fraud constellations.

3. The game‑changing compensation model that was on the table

The Commission proposal would have fundamentally shifted this model:

Article 16(1) would have been tightened so that victims, as a rule, obtain a decision on their compensation claim within the criminal proceedings, effectively neutralising the escape clause.

Member States would have been obliged to pay the awarded compensation directly to victims “in due time” after the judgment and then recover the money from the offender.

For online investment fraud victims, including those residing in a different Member State from where the complaint is filed, this combination would have been transformative: victims would no longer be routinely referred to separate civil lawsuits, often in other countries, and would no longer carry the full enforcement risk once a criminal court awarded compensation. The state would have to advance the money and then pursue recovery, using its own investigative powers and cross‑border tools.

For the first time, the EU was considering a functional compensation system for all crime victims, grounded in criminal proceedings, without civil‑procedure escape routes and backed by state pre‑financing. For online investment fraud victims, this is exactly what has been missing for more than a decade.

4. What the European Parliament added in 2024: strong legal aid and real remedies

In March 2024 the European Parliament adopted its report A9‑0157/2024, which not only endorsed the Commission’s direction but went further in several crucial areas

4.1 Coordinated, accessible victim support

Parliament insisted that general and specialist victim support services must be accessible to all victims on a non‑discriminatory basis, available before, during and for a certain time after criminal proceedings, free of charge and confidential, and provided through multiple channels, including in rural areas. Services should be coordinated so that victims are referred to appropriate support according to their needs, and psychological support should be available “for as long as necessary” where an individual assessment shows a need.

4.2 A real right to legal aid

Recognising that legal aid is essential for effective participation, Parliament proposed free legal aid covering all costs for victims who lack sufficient means, and automatic free legal aid regardless of income for victims with specific protection needs (for example, gender‑based violence, terrorism, trafficking, minors, and certain victims with disabilities). This approach would have given many online fraud victims – often older, vulnerable and facing substantial losses – a realistic way to access lawyers and challenge decisions.

4.3 Compensation and cross‑border rights

Parliament also strengthened victims’ right to claim and obtain a decision on compensation from the offender within criminal proceedings and improved provisions for cross‑border victims, including through video links and clear recognition that rights can be exercised irrespective of the victim’s Member State of residence. It wanted explicit rights for victims of cross‑border crime to access 116 006 helplines in any Member State, reinforcing the cross‑border dimension crucial for online scams.

For cross‑border online scam victims, this combination – state‑backed compensation, strong legal aid, and explicit cross‑border access rights – finally addressed the structural deficits that EFRI has highlighted for years.

5. What the Council did in 2024: turning obligations into options

On 13 June 2024, the Council adopted its general approach to the reform. On the surface, the press release sounded positive: easier online crime reporting, emotional support at court, and an EU‑wide helpline via 116 006.

But as in a joint statement by Victim Support Europe and dozens of NGOs pointed out the Council position shows “little willingness to commit to enhancing victim rights” and “largely rejected or diluted the Commission’s proposals, turning obligations into mere options”.

According to victim organisations, the Council’s version removed or weakened key rights, including safe reporting of crime, court‑based support services, access to medical services, privacy protections, information and participation rights, offender compensation, and legal remedies. In other words, precisely those parts that would make rights enforceable in practice were placed under pressur

6. The final December 2025 compromise: helplines yes, compensation no

On 10 December 2025, the Council and Parliament announced a provisional agreement on the revision of the Victims’ Rights Directive.

The good news: helplines, online reporting, some legal aid

According to the Council’s press release, the compromise includes:

Victims’ helplines via 116 006

Member States must provide victims’ helplines offering information, emotional support and referrals to services.

Across the EU, they will be reachable under the harmonised number 116 006, with some services also delivered via IT tools (online, chat).

Online and third‑party crime reporting

Member States must ensure that victims can report offences through user‑friendly information and communication technologies, including the possibility to submit evidence.

Authorities must also facilitate third‑party reporting (e.g. NGOs that receive information from victims).

Legal aid – but only for some victims

Victims who have the status of parties in criminal proceedings and do not have sufficient means will receive access to legal aid; Member States may apply means and/or merit tests.

Some categories of victims, defined by each Member State, must always be entitled to legal aid if they both lack sufficient means and have party status.

These points are useful. For online fraud victims, easier online reporting and a single EU helpline number could lower the threshold to seek help.

7. The decisive retreat: compensation and state responsibility

The compensation chapter is where the final text falls far short of what the Commission and Parliament proposed – and where the two really important reforms were lost.

The escapt clause survives:

Most strikingly, the final compromise does not amend Article 16(1) at all.

This means that the old wording from 2012 remains in force, including the escape clause that allows Member States to provide that decisions on compensation are taken in other legal proceedings (typically civil courts), not in the criminal trial.

In practice, this is exactly what we see in Germany (adhesion procedure) and Austria (Privatbeteiligtenanschluss):

Courts often refuse to substantively deal with victims’ compensation claims in criminal proceedings and

refer victims to the civil courts, with all the costs, delays and cross‑border hurdles this involves.

State advance payments reduced to a narrow, optional tool:

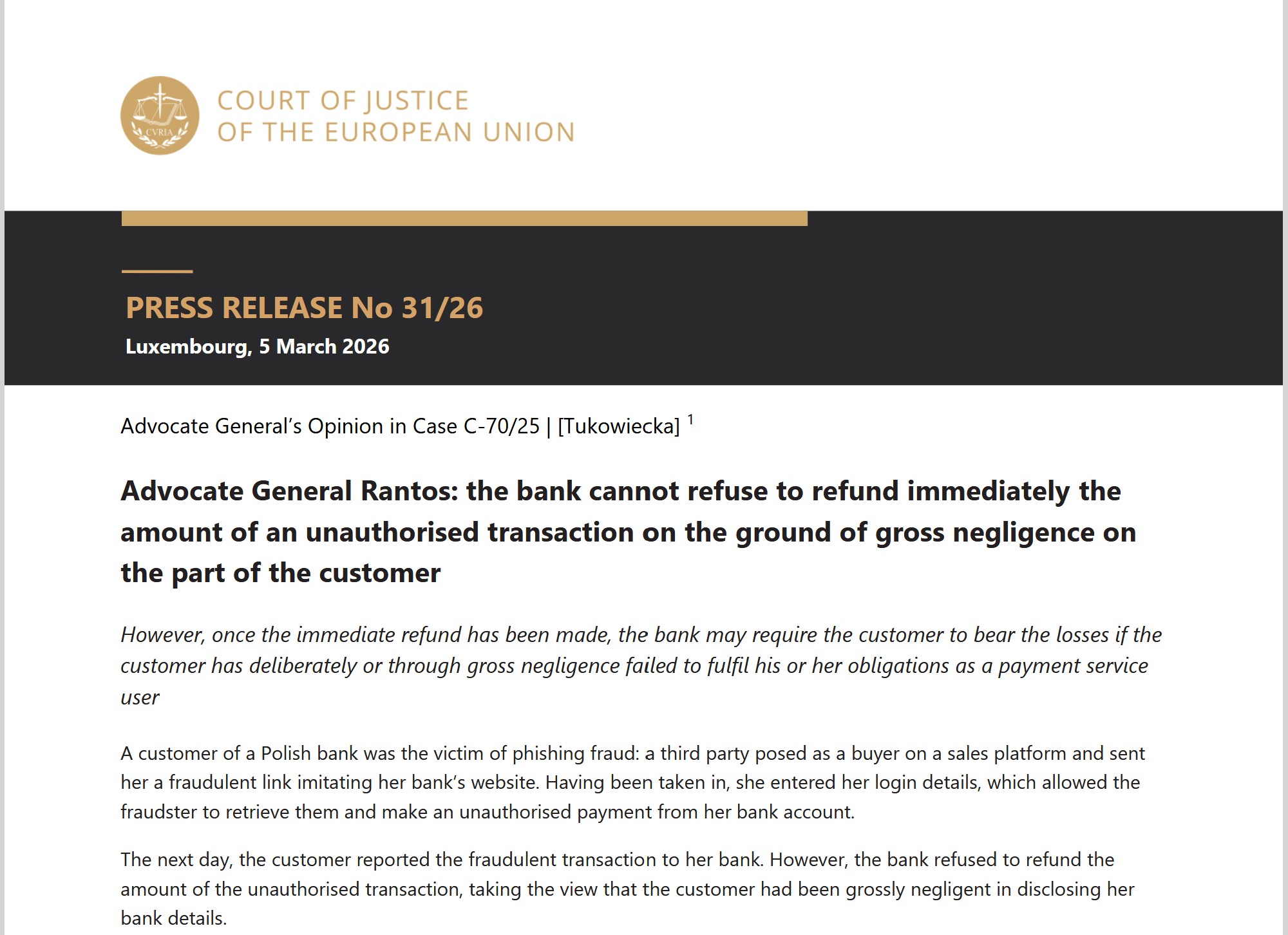

The final agreement provides that Member States must adopt execution or enforcement measures to help secure compensation from offenders, essentially to speed up implementation of court decisions. However, only for victims of violent intentional crimes, and only where the convicted offender does not pay within a reasonable time, may Member States choose to advance the awarded compensation and later recover it – and even this is optional.

By contrast, the Commission’s original proposal would have required Member States to pay adjudicated compensation directly and quickly to all victims after a judgment and then seek recovery from offenders. For online investment fraud, which is generally treated as non‑violent property crime, the final Directive does not oblige states to advance compensation at all, leaving victims with either a paper decision against an untraceable or insolvent offender, or no decision because courts use the escape clause to point them to civil courts.

In short: the state guarantee of compensation that could have transformed the situation for online fraud victims did not survive the negotiation, while the escape clause enabling courts to push victims into civil proceedings remains untouched

8. What this means in practice for online investment fraud victims

For the EFRI community – victims of online investment fraud and mass online scams – the new Directive delivers only marginal improvements and no structural change.

Small steps forward

Online and third‑party reporting may make it easier to file complaints, including in cross‑border situations, and the EU‑wide number 116 006 should in theory serve as a recognisable entry point for support services in any Member State. These changes reduce formal barriers at the beginning of the process, but they do not alter the outcome once cases enter the criminal justice system.

Core problems remain untouched

No effective route to compensation: without a compulsory state advance, online fraud victims remain dependent on offenders who are often abroad, anonymous or bankrupt. Enforcement measures are meaningless if nothing is left to enforce or if courts never award compensation because they send claims to civil courts.

Weak and conditional legal aid: legal aid depends on the victim having party status in criminal proceedings, a status many fraud victims never obtain because authorities classify their case as “civil” or too complex, and even then legal aid can be restricted by means and merit tests.

No link to financial and digital infrastructure: the Directive remains confined to criminal procedure and does not address the role or responsibility of banks, payment providers, crypto exchanges or online platforms that host fraudulent advertising – even though these intermediaries are often the only actors in the EU with assets.

Recognition as crime victims not guaranteed: the Directive protects “victims of crime”, but if police or prosecutors refuse to treat online fraud as crime, there is no direct remedy in the Victims’ Rights framework.

There is still no EU‑level right to state compensation for victims of cross‑border financial crime, and the state does not step in when offenders are in another country, cannot be identified, or have no assets. For cross‑border fraud victims, the Directive improves access to procedures, but not the likelihood of getting their money back.

9. What EFRI expects from Member States and EU institutions

From EFRI’s perspective, the message is clear: the revised Directive sets a floor, not a ceiling. Member States and EU institutions must go beyond the minimum, especially on compensation for online fraud victims.

Member States must go beyond the minimum on compensation

Member States should use the flexibility of the new Directive to extend state advance payments to all crime victims, including large‑scale online fraud, and not only to victims of violent intentional crimes. National schemes should ensure that the state pays out compensation after criminal judgments – or, where appropriate, after administrative findings – and then pursues regress against offenders and facilitators, including financial intermediaries.

Online fraud victims must be a priority for legal aid

Member States should define victims of major online investment fraud as a priority category for legal aid, always entitled to assistance where they lack sufficient means. Without accessible legal representation, the formal rights in the Directive will remain largely theoretical for this group.

Victims’ rights must be connected with financial regulation and platform rules

The Victims’ Rights Directive alone cannot fix online fraud; it must be complemented by PSD3/PSR, AML rules, Digital Services Act enforcement and MiCA, all of which must be explicitly linked to victim compensation and redress. Liability rules for banks, payment providers, crypto exchanges and online platforms that profit from fraudulent transactions or advertising are essential to make compensation realistic in cross‑border scams.

Monitoring of transposition must be hard‑headed and data‑driven

The Commission should not limit itself to checking national laws on paper; it should monitor how the Directive works in practice, including

- how many online fraud cases are registered as crime,

- how many victims obtain party status, how many receive legal aid, and

- how often compensation is actually paid – and by whom. Only such data‑driven monitoring will show whether the promise of “strengthened victims’ rights” translates into real redress for online fraud victims in the EU.