On 27 November 2025, EU negotiators announced a political deal on the new Payment Services Regulation (PSR) and PSD3. The press releases promised a “historic step” against payment fraud, more protection from online scams and new liability rules for social media platforms.

From the perspective of EFRI, and against the evidence we documented in our paper “Restoring Trust in European Payment Rails: A Framework for a Shared Liability Reform”, this is not a historic breakthrough. It is the weakest possible version of APP fraud reform. It leaves the core social media scam economy intact and most victims of authorised push payment (APP) fraud without real protection.

This blog posting explains why the new PSR and PSD3 fraud provisions are largely a cosmetic fix, why the new platform liability rule is an empty shell, and why our own reform proposal now looks almost too polite in hindsight.

Important caveat: the final PSR/PSD3 text is not yet public

As of today, the final legal text of the PSR and PSD3 trilogue deal adopted on 27 November 2025 has not been published. There is no consolidated regulation or directive text available on EUR-Lex reflecting the compromise between Council and Parliament.

Our analysis is therefore based on:

the original Commission proposals for PSR and PSD3,

the Parliament and Council positions before trilogue, and

the very limited information disclosed in official press releases after 27 November 2025.

So far, EU institutions have effectively communicated only two core elements of the fraud package:

A new reimbursement duty for APP fraud that is limited to bank / PSP impersonation cases.

A new, very narrow regress-based liability rule for major online platforms and search engines, which applies only where PSPs have already reimbursed victims of such bank impersonation APP fraud.

Everything else remains vague. No public legal text shows how the agreed compromise will be drafted in detail, how definitions are framed or how enforcement will work. That makes it even more worrying that the only clearly communicated elements are already extremely narrow.

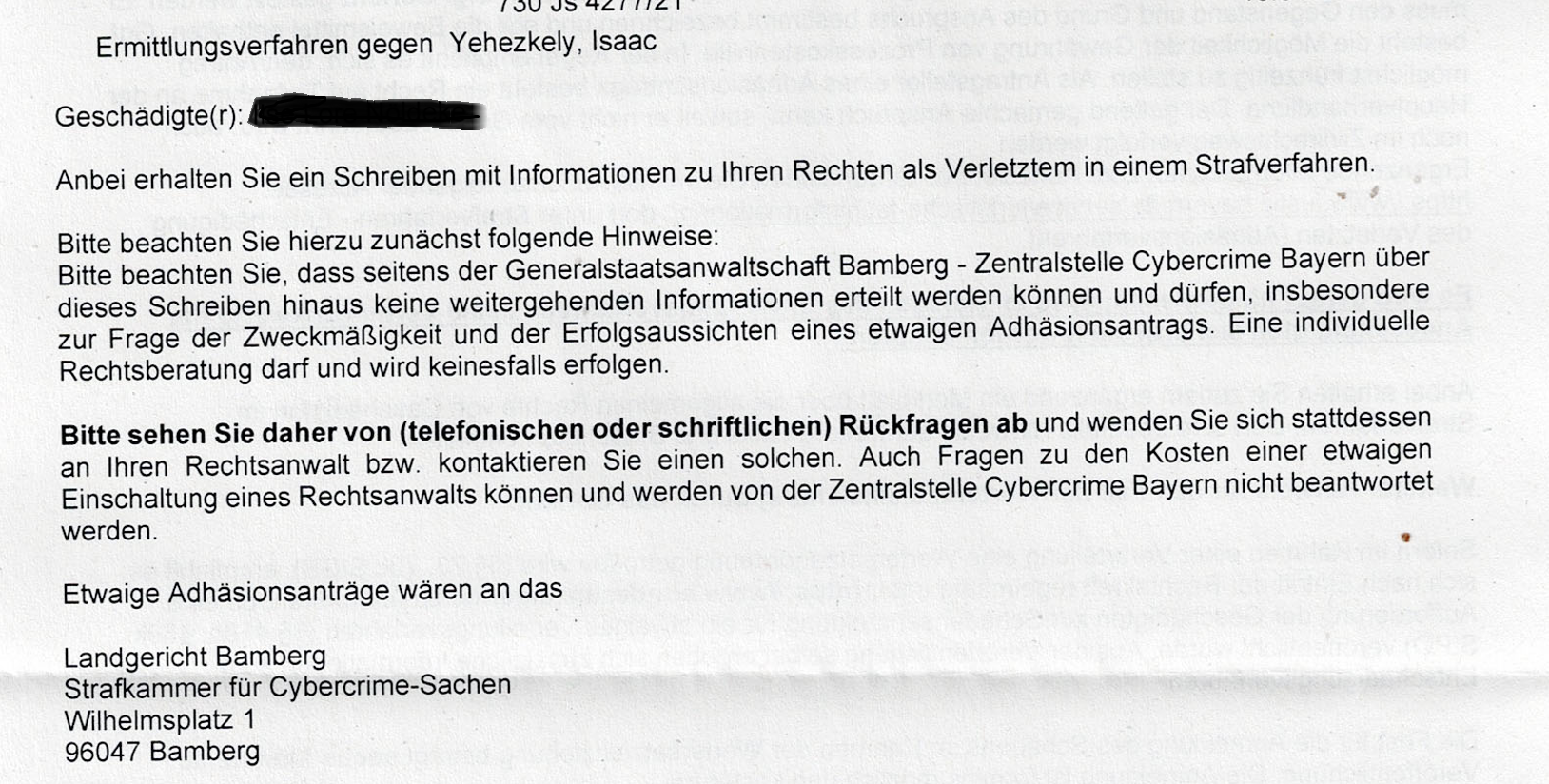

What our APP fraud data shows – and how it contradicts the PSR and PSD3 narrative

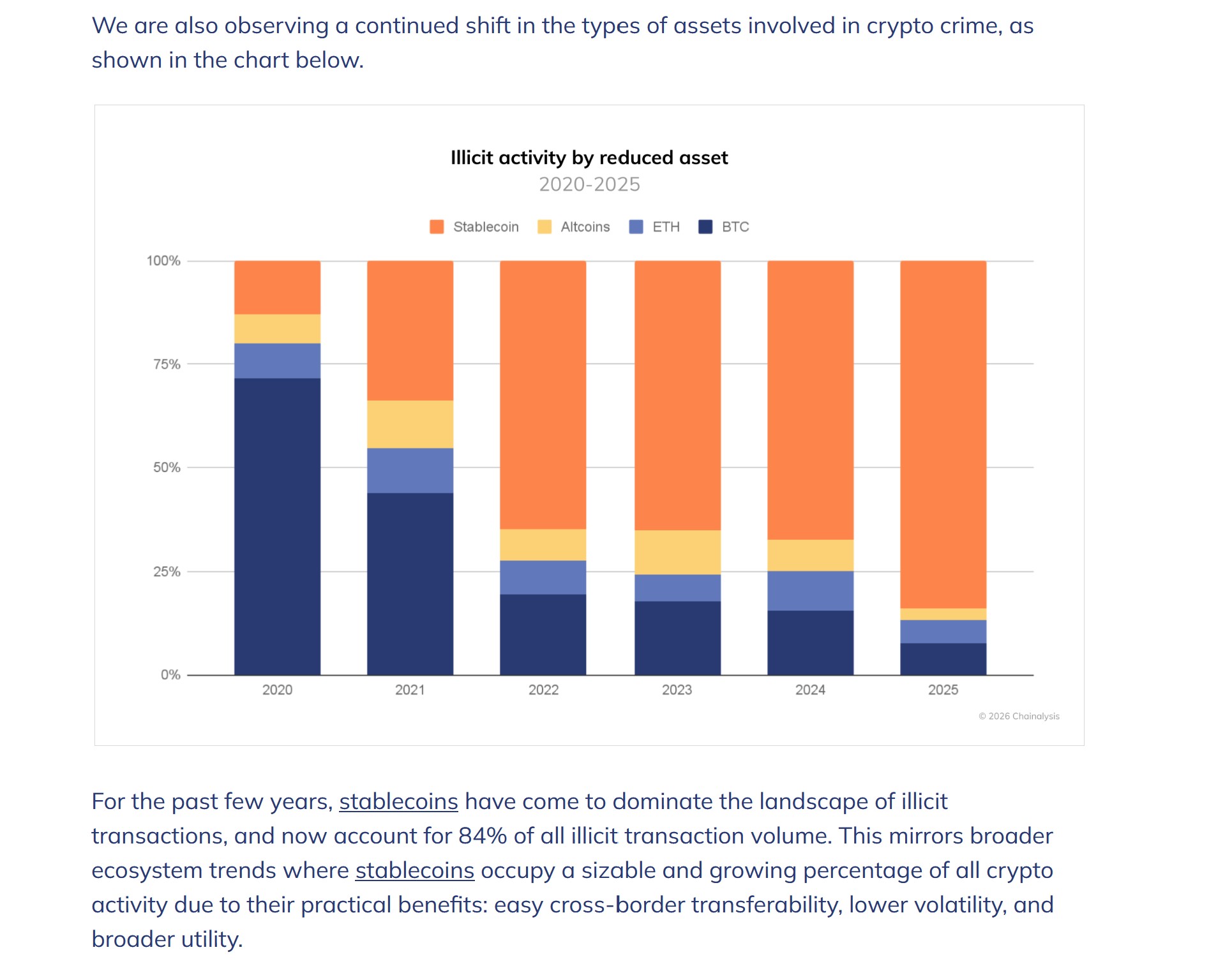

EFRI collected data on 1,750 fraud cases from 20 countries with total losses of €62.5 million, mostly in online investment and “pig butchering” scams. The majority of these cases are APP fraud in the strict PSD2 sense. Victims themselves initiated credit transfers, card-not-present payments or crypto purchases, but they did so under heavy deception and manipulation.

Our data shows several important facts:

Victims are not mainly “greedy day traders”. Most are 50–70-year-old conservative savers with limited experience in financial markets.

More than two thirds first encountered the scam through online advertising on social media or search engines. Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Google are central in the victim journey.

The typical pattern involves fake online investment platforms, boiler rooms, fraudulent crypto schemes and pig butchering scams, not bank impersonation fraud.

A small and recurring set of EU payment institutions and banks processed these transactions as acquirers, EMIs, payment intermediaries and beneficiary banks, often for years, despite clear red flags.

Based on this evidence, our paper argued for three core elements of a real APP fraud reform:

Redefine consent for APP fraud. Payments that are authorised under deception should be treated as unauthorised for liability purposes. Consent given under fraud is not meaningful consent.

Outcome-based reimbursement for APP fraud victims. The payer’s bank or account-servicing PSP should be the reimbursement anchor for all fraud-induced payments, with calibrated recourse along the scam chain towards acquirers, beneficiary banks, platforms and telecoms.

A shared liability framework combined with FIN-NET 2.0. Liability should follow the actors who control risk, and there should be an EU-level ombudsman structure with binding powers so that victims can actually enforce their rights.

We described two possible “landings” for PSR: a narrow version and a broad version. Only the broad version would have matched the empirical reality of APP fraud and restored trust in European payment rails.

The political deal on PSR and PSD3 has now chosen something even weaker than our narrow landing – and the only clearly communicated parts are already a retreat from what is needed.

What PSR and PSD3 actually change on payment fraud

Stripped of the marketing language, the PSR and PSD3 deal concluded on 27th of November 2025 does three main things in the area of payment fraud and APP fraud:

It creates a highly restricted reimbursement duty for APP fraud.

PSPs will only be required to refund victims for a very narrow category of APP fraud: PSP impersonation. This category covers cases where the scammer pretends to be the victim’s own bank or payment provider and, on that basis, persuades the victim to authorise a transfer.It introduces a very limited platform liability rule.

Social media platforms can only be held liable by PSPs that have already reimbursed their customers (for bank impersonation!)It avoids structural reform of enforcement and redress.

The deal does not meaningfully strengthen enforcement of existing PSD2 and PSR duties. It does not create an EU-level, binding ADR mechanism for APP fraud victims. It does not impose real consequences on supervisors who fail to enforce the rules.

The essential logic is very simple:

If a bank or PSP does not reimburse an APP fraud victim, then the platform pays nothing.

PSPs are only obliged to reimburse in PSP impersonation cases, plus a very small set of other APP cases where they voluntarily accept liability.

As a result, the new rule for platform liability is, in practice, almost never triggered

Why focusing only on bank impersonation APP fraud misses most real-world scams

The new reimbursement duty for APP fraud focuses almost entirely on PSP impersonation. This is the specific scenario where a scammer pretends to be a bank or payment provider, for example by calling as “the bank’s security department” and persuading the victim to authorise a transfer.

There is no doubt that such cases are serious. However, compared to the overall APP fraud landscape, they are only a minority. In public statistics, the dominant fraud types are:

Fake online investment platforms and aggressive trading scams.

Boiler room operations promising unrealistic returns.

Pig butchering and romance scams that combine emotional manipulation with fake investments.

Recovery scams that exploit victims a second time by pretending to help them recover their losses.

These frauds do not rely on impersonation of a bank. They rely on manipulation, persuasion, and the exploitation of trust built through advertising, social media contact, and carefully scripted communication. Yet these are exactly the fraud types that PSR and PSD3 refuse to address through a mandatory EU-wide reimbursement mechanism.

By limiting the new protection to PSP impersonation, the EU has created a flagship APP fraud rule that only covers a small slice of the problem. For most victims of online investment scams and pig butchering fraud, nothing significant has changed.

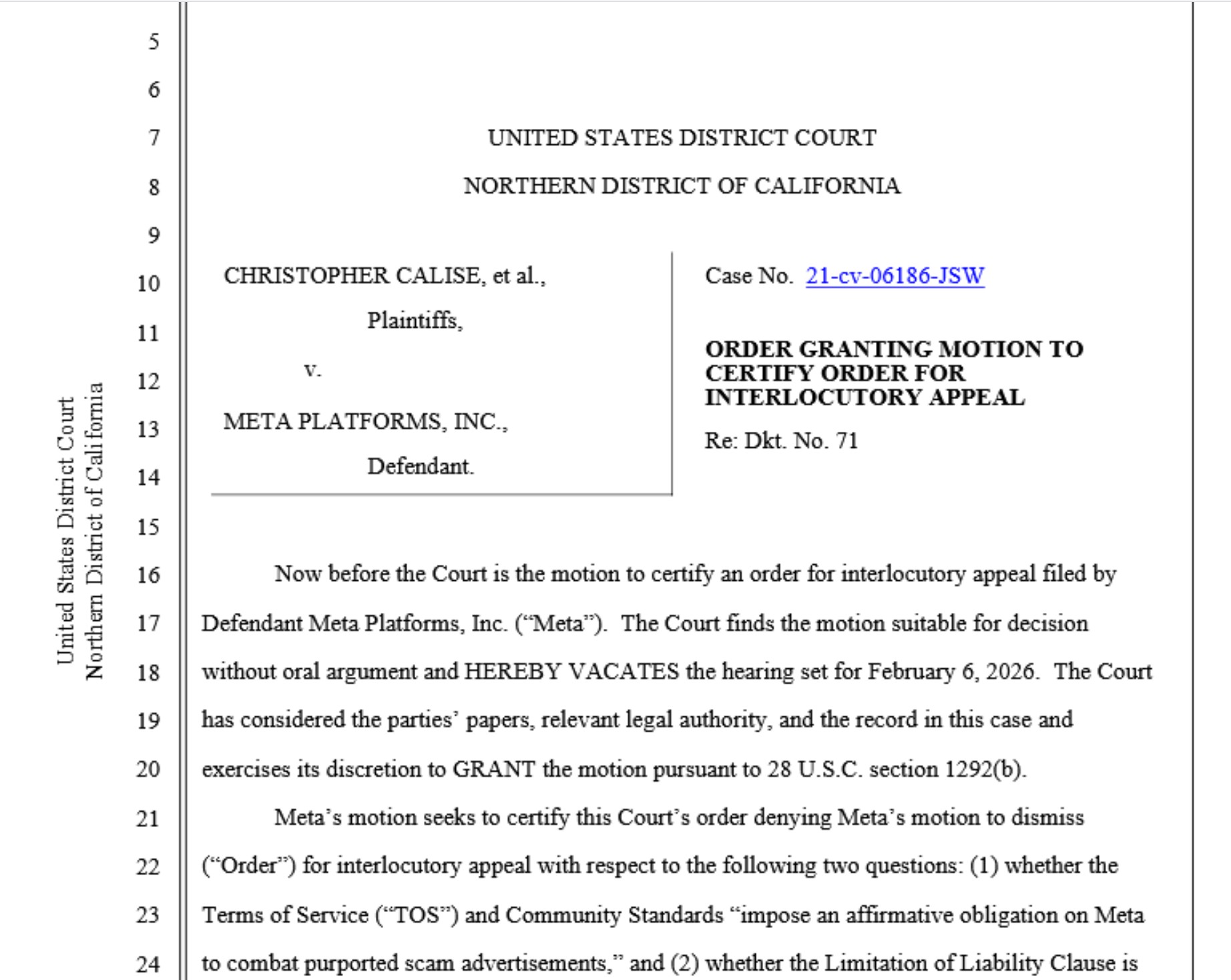

Why the new platform liability rule is an empty shell for social media scams

The second political selling point of the PSR and PSD3 deal is the promise of platform liability. On closer inspection, this liability is extremely narrow and dependent on prior action by banks.

The structure works as follows:

A bank or PSP first reimburses the victim of bank impersonation APP fraud.

Only after that reimbursement has taken place, the bank may attempt to recover its loss from a social media platform.

The bank must then prove that:

the platform was explicitly informed of specific fraudulent content,

the platform did not remove this content in time, and

this exact content caused the fraud in question.

There are several obvious problems with this design:

Up to today we have not seen a single social media ad for “bank impersonation fraud”. Social media platforms monetise investment scams, fraudulent brokers, fake trading systems and other deceptive offers, not explicit claims of “we are your bank”. If PSPs are only required to refund APP fraud in bank impersonation cases, the new liability rule for social media platforms is, in practice, largely an empty shell.

If the PSP refuses to reimburse the victim, the case ends there. The victim has no direct claim against the social media platform under PSR or PSD3.

The result is a platform liability rule that looks strong in press releases but is almost toothless in real life. It does not alter the core business model of social media platforms, which is to sell targeted advertising, including for “too good to be true” financial products and outright scams.

What a real shared liability framework for APP fraud would require

The contrast between our framework and the PSR and PSD3 deal is now very clear. A meaningful reform of APP fraud and online payment fraud in Europe would require:

Technology-neutral outcome rights for victims.

Victims of APP fraud should have an EU-wide right to reimbursement, regardless of whether the fraud began on social media, via phone, via email or via text messages.Reclassification of fraud-induced payments.

Payments that are authorised under deception and manipulation should be treated as unauthorised for the purpose of liability and reimbursement. Consent under fraud is not consent.Joint and several liability along the fraud chain.

Liability should be shared between the payer’s PSP, acquirers, beneficiary banks, social media platforms and telecom operators, depending on their role in enabling and profiting from the fraud. Victims should not have to identify the right defendant. They should be able to claim against one party that can then seek contribution from the others.An EU-level ADR and enforcement structure with real powers.

A FIN-NET 2.0 should be able to issue binding decisions in cross-border APP fraud disputes. Supervisors who consistently fail to enforce consumer protection rules should face consequences.

Only such a shared liability framework would meaningfully align incentives, push actors to invest in prevention and truly protect EU citizens from online fraud.

Conclusion: PSR and PSD3 protect the system, not the victims of APP fraud

The new PSR and PSD3 package is being sold as a major step forward in the fight against payment fraud and online scams. Our analysis, rooted in real victim data and in the lived experience of EFRI members, paints a very different picture.

The new APP fraud reimbursement rule applies only to PSP impersonation and ignores the dominant fraud patterns we see in practice, especially online investment scams and pig butchering fraud.

The new platform liability rule depends entirely on prior reimbursement by PSPs and is therefore largely an empty shell in cases where banks refuse to pay.

The enforcement and data gaps that already undermined PSD2 are left almost untouched, so the same institutions that failed victims in the past remain in control.

The final PSR and PSD3 legal text is not yet public, and the only clearly communicated elements are already too narrow to address the real APP fraud crisis.

Europe has chosen to protect the appearance of action instead of addressing the reality of APP fraud and online financial crime. The EU has not delivered on the promise to make digital payments safe for ordinary consumers and savers.

EFRI will continue to document cases, to support victims and to push for a real shared liability reform that redistributes losses away from victims and towards those who design, operate and profit from the systems that criminals exploit. Until such a reform exists, we will keep saying clearly what PSR and PSD3 are:

A cosmetic fix that protects the rails and the platforms, not the people who trusted them.