The digital-asset market is slowly running into exactly the same legal questions that have shaped traditional payment law for decades: Who is liable when an inter-exchange transfer fails, is misrouted, or reaches a blocked address? Can doctrines like the Drittschadensliquidation (DSL, third-party damage liquidation) – developed in German banking law – also be applied to blockchain-based transfers and to payment processors such as Payvision?

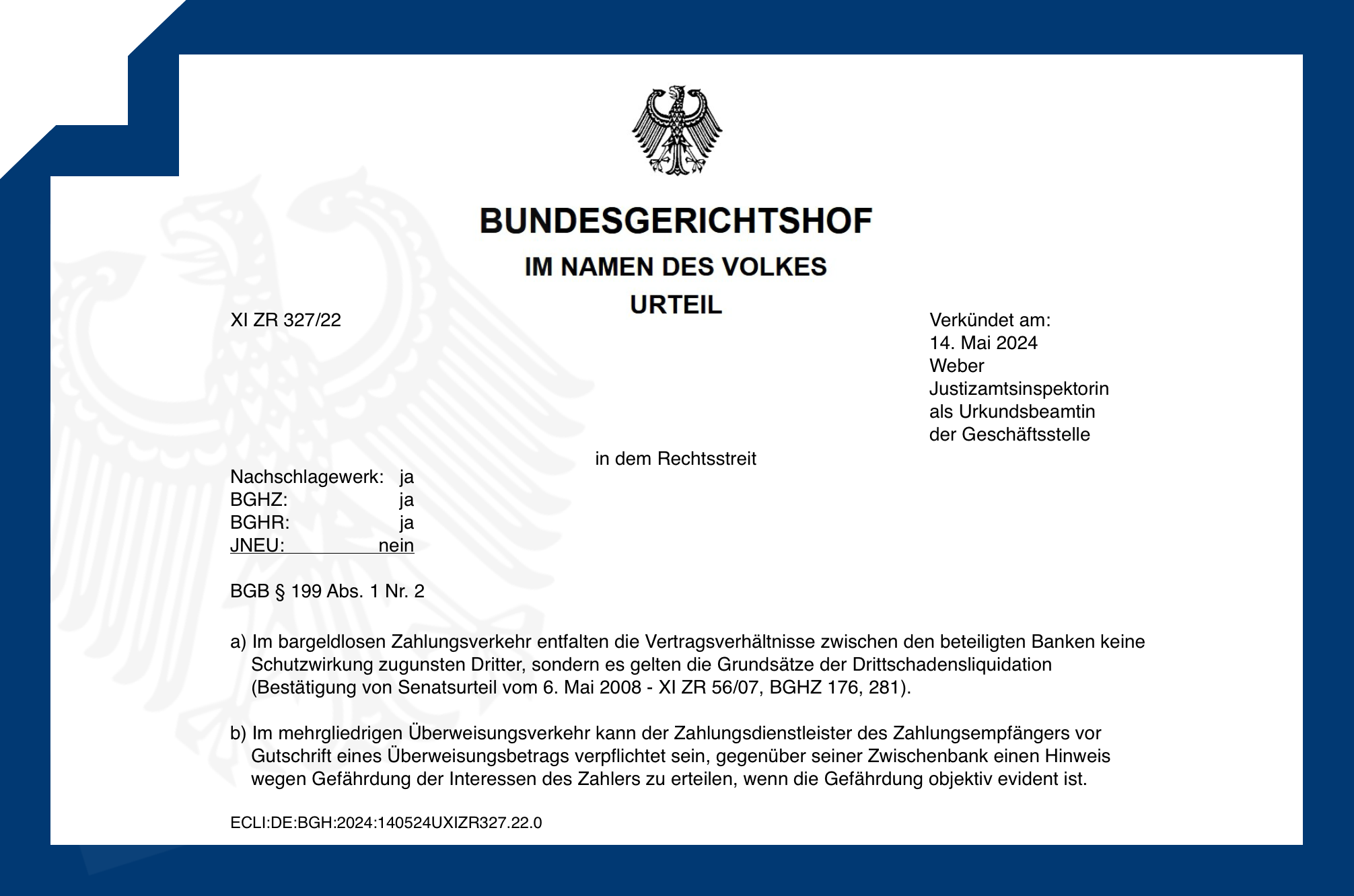

A ruling of the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH) from 14 May 2024 (XI ZR 327/22) makes one thing very clear: liability in multi-layer payment chains does not arise because customers are “third-party beneficiaries” of bank contracts. It occurs because banks participate in a normatively structured clearing system – and within that system, they owe each other concrete duties of care, including a duty to warn about obviously dangerous transactions.

The question for us is: how far can this reasoning be carried over to card-payment processors like Payvision – and to regulated crypto platforms that sit on top of blockchains?

What the BGH actually decided – and why DSL stays central

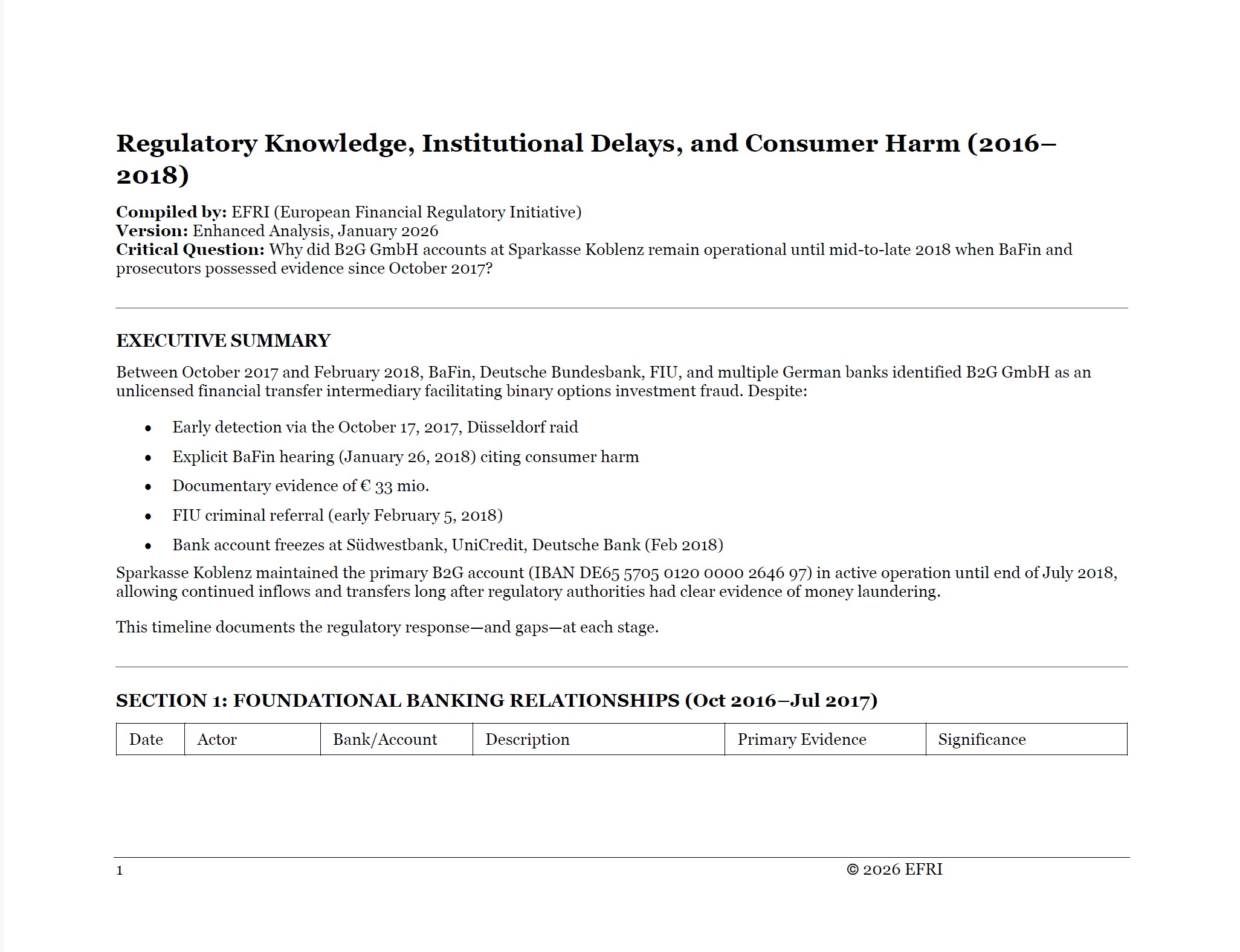

In XI ZR 327/22, the BGH addressed a familiar constellation: a multi-tier cross-border transfer in which the economic loss arises from relationships that exist only between banks. The payer instructed his bank to transfer funds to a Swiss financial company; in the background, several correspondent banks and the recipient bank were involved. Before the transfer, FINMA had already prohibited this company from taking public deposits and had appointed investigative officers.

The recipient bank processed the payment and failed to warn the upstream banks. The investment predictably disappeared in the insolvency.

The BGH clarifies several key points:

No “contract with protective effect for third parties” between banks and customers

The contracts between the banks in the clearing chain do not extend protective effect directly to the customer. The BGH explicitly rejects this construction for normal giro/clearing relationships. Instead, third-party losses are handled via DSL: the payer’s bank has to assign its claims to the payer in order to enable the payee to claim refunds.

Duty to warn based on objectively evident risk

As a rule, a payment service provider does not need to investigate each single payment transaction (“Valutaverhältnis”). But an exception arises where there is objectively evident danger to the payer’s interests – here, the FINMA order banning the receipt of deposits and appointing investigators. In such cases, the recipient bank must warn its correspondent banks, which in turn must pass the warning through the clearing channels to the payer’s bank so that the payment can be stopped before final crediting.

Presumption of “aufklärungsrichtiges Verhalten” (causality)

If this duty to warn is violated, the BGH applies the presumption of correct conduct: it is presumed that a reasonable customer would have reacted to the warning and avoided the loss. The burden shifts to the bank to prove that the loss would have occurred anyway – a genuine reversal of the burden of proof.

Limitation period in DSL cases: knowledge of the assigning bank counts

In a DSL structure the claim is first held by the customer’s bank and only later assigned to the customer. For the limitation period under § 199 I Nr. 2 BGB, the BGH holds that the relevant “knowledge” is that of the assigning bank, not the end customer. The statute may therefore start – and even expire – before the customer knows anything about their legal position.

The core message: liability in multi-layer payments is built on an institutional clearing system and on DSL – not on creative third-party beneficiary doctrines.

2. Clearing systems in classic payments – and why this matters for our Payvision case.

For the BGH, the decisive pre-condition for applying DSL in payments is the presence of a normative clearing structure:

Banks are bound into systems such as SEPA, TARGET2 or the domestic giro-clearing arrangements.

Participation is governed by contractual rules and regulatory oversight.

Each bank acts “im eigenen Namen, aber im Interesse der Kunden” of the previous bank – a classic constellation of mittelbare Stellvertretung in a fixed chain.

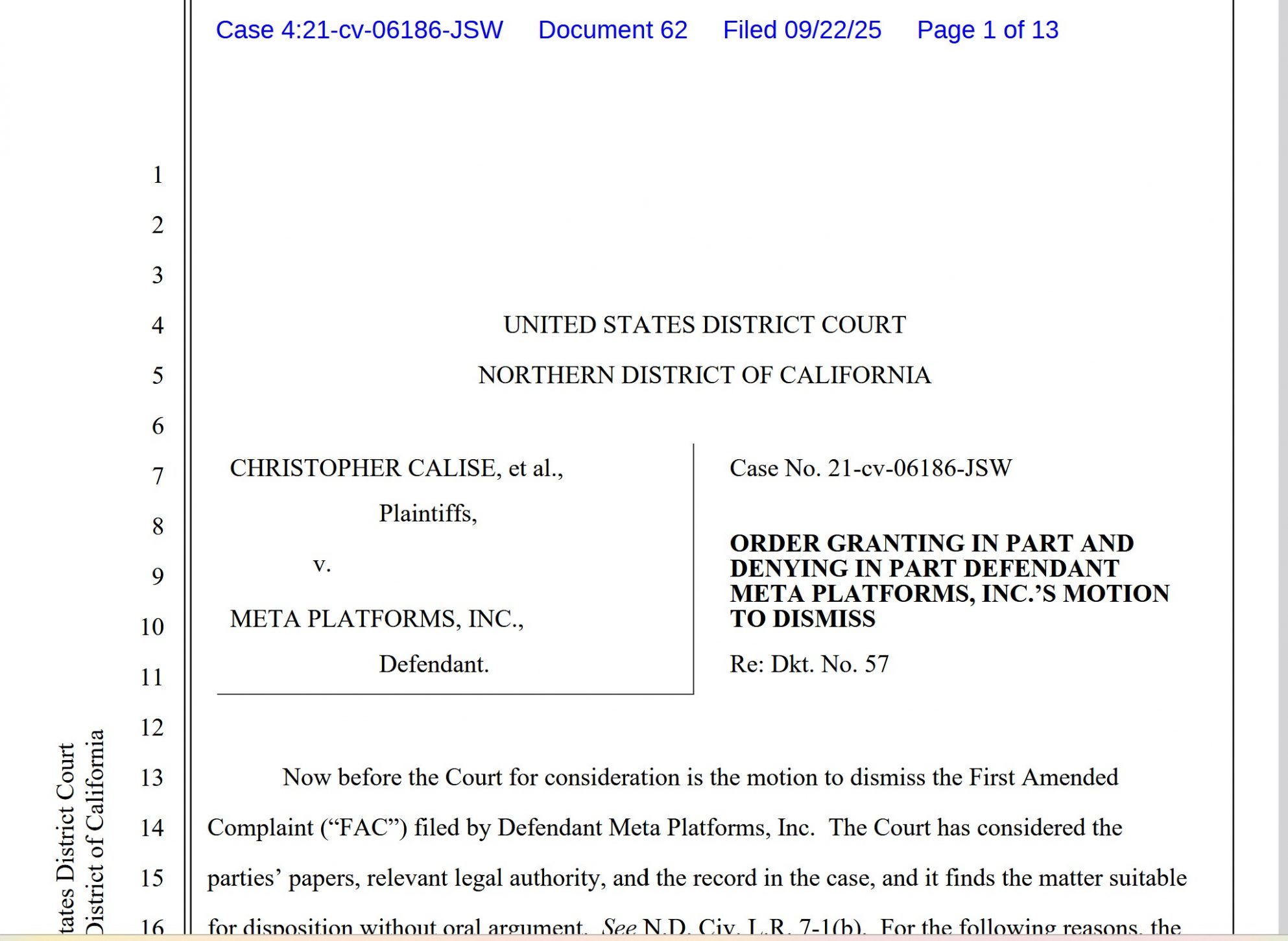

So what about our pending German Payvision case?

If we look at card payments processed by Payvision and similar acquirers, the functional parallels are striking:

The card schemes (Visa, Mastercard, etc.) provide the institutional framework for clearing and settlement, with detailed scheme rules.

Issuing banks, acquiring banks and payment processors like Payvision are tied into this system via multi-layer contracts.

Chargeback rules, monitoring programmes and scheme fines create a dense web of obligations and information flows.

From an EFRI perspective, the BGH ruling strengthens the argument that this card-clearing universe is a clearing system in the same sense as the giro system:

When an acquirer such as Payvision reaches excessive chargeback ratios, receives scheme warnings, has merchants flagged by law-enforcement or is subject to supervisory warnings, this is information that – under the BGH logic – most proably amounts to at least “objectively evident” risk. (we should not forget that Payvision’s CEO Rudolf Booker even joined Uwe Lenhoff‘s birthday party.

The acquirer then cannot simply hide behind “purely technical processing”. Within the clearing system it has a duty to warn upstream parties, particularly the card schemes and issuing banks, and ultimately to stop processing fraud-driven merchants.

In other words: Payvision did not operate in a legal vacuum. It acted within a normatively structured clearing environment – and the BGH shows that within such structures, a duty to warn and a DSL-style allocation of losses are entirely appropriate ( in our view).

From a Payvision-perspective, this has teeth: Payvision’s entire business model as an acquirer was embedded in the card-clearing system and subject to scheme rules and supervisory oversight. When acquirers and their partner banks collectively ignored massive fraud signals, the BGH benchmark for “objectively evident risk” and the presumption of causality became a powerful argument for victim-side litigation – not only in Germany, but across the EU.

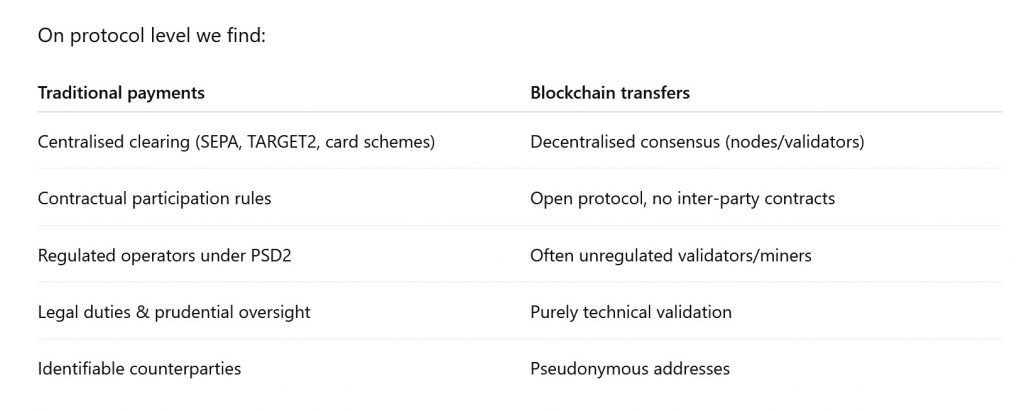

Why pure blockchain transfers are different – and where MiCA (in our view) changes the picture

If we move to a pure blockchain setting (for example, a direct Bitcoin transaction from one self-custodial wallet to another), the BGH framework is no longer applicable.

There is no contractual clearing chain between validators; no SEPA-style rules; no bank-like counterparties that could warn each other; and, most importantly, no possibility to halt or reverse a transaction once the block is finalised. The entire logic of the BGH duty to warn (intercepting a transfer before final crediting) collapses at the protocol level.

But there is room for interpretation:

However, this does not mean that blockchain-based markets are beyond the reach of the BGH reasoning. The gap could be closed by EU regulation:

MiCA transforms Crypto-Asset Service Providers (CASPs) – exchanges, custodians, certain brokers – into regulated financial institutions with governance, capital and conduct-of-business obligations.

The Transfer of Funds Regulation (TFR) extends the FATF Travel Rule to crypto, forcing CASPs to collect and transmit originator and beneficiary data for transfers.

Together, MiCA and TFR could be interpreted as re-creating a normative clearing structure on top of the blockchain:

Regulated CASPs form an identifiable, contractually connected chain for on- and off-ramps, platform-internal transfers and inter-CASP settlements.

Each CASP must perform AML/KYC, address screening, sanctions checks, and ongoing transaction monitoring.

The resulting information – red-flag indicators, lists of scam wallets, supervisory orders, law-enforcement inquiries – gives CASPs exactly the kind of “objectively evident” knowledge the BGH had in mind.

Suppose a CASP continues to route customer funds to a clearly blacklisted scam address, without warning its customers or counterpart CASPs. In that case, this appears alarmingly similar to the recipient bank in XI ZR 327/22, which ignored the FINMA order. The functional duty to warn is the same – only the rails have changed.

DSL, limitation periods and strategic options for victims

Transferring the DSL logic into the crypto/CASP world is attractive but comes with technical traps – especially on limitation periods.

If courts treat CASPs like banks in a clearing chain, then the claim would first arise at the CASP level (e.g., the platform routing the transfer) and only later be assigned to the end customer.

Under XI ZR 327/22, the limitation period starts running when the CASP has the necessary knowledge, not when the retail customer finally realises they were defrauded.

Conclusion: Clearing systems are legal structures, not just technical rails

The BGH decision XI ZR 327/22 sends a clear message that is highly relevant for Payvision and for the future of crypto regulation:

Liability follows normative clearing structures, not marketing slogans about “purely technical processing”.

Within such structures, participants owe each other – and indirectly the end users – a duty to warn whenever regulatory or factual information makes fraud risks objectively evident.

For card-payment processors like Payvision, the card-scheme environment is precisely such a clearing system.

- For crypto, MiCA and TFR could be an ankle for creating an analogous system for CASPs (from our point of view).

The blockchain itself is not (yet) a clearing system in the BGH sense. But the regulated layers built on top of it are – and that is where future liability battles will be fought. For victims of online-investment fraud, this offers a clear strategic direction: focus on the regulated intermediaries who had the information, had the duty to act – and chose not to.