Phishing is not a “private misfortune.” It is a systemic failure of payment security, and German courts are—slowly—drawing the lines of responsibility. Below is a concise map of key judgments (2023–2025) you can cite when you push your bank for reimbursement under §§ 675u, 675v, 675w BGB (PSD2). At the end, you’ll find direct links to the decisions and solid. summaries

What is pishing?

Phishing (including smishing by SMS and vishing by phone) is a social-engineering attack in which criminals impersonate banks, delivery firms or authorities to trick customers into disclosing credentials, reading out or approving TAN/2FA codes, or approving actions in the banking app (e.g., device binding, limit increases, card provisioning to Apple/Google Pay). The contact typically uses spoofed sender IDs, look-alike domains and urgent scripts (“security update,” “account at risk”). The aim is to trigger payment orders or alter security settings so funds can be moved. Even where strong customer authentication (SCA) appears to have been used, the transaction is an unauthorised payment if the payer never intended that specific transfer; under PSD2 and its German implementation (§§ 675u–675w BGB), the bank must refund unless it proves fraud or gross negligence by the customer.

Despite PSD2’s refund-first regime for unauthorised payments, banks and other payment service providers (e.g. PayPal) often deny liability and blame customers, compelling many victims to pursue civil proceedings to obtain reimbursement. So right now, dozens of defrauded consumers are pending with German courts about similar cases. And – unfortunately and unsurprising – right now, German courts very often share the banks’ view on gross negligence of the bank consumers .

In the following, we share the most relevant decisions for this topic:

The top line from the BGH (Federal Court of Justice)

BGH, 5 March 2024 – XI ZR 107/22

Burden of proof sits with the bank. In disputes about unauthorised transactions, the bank must prove authorisation/strong customer authentication; customers don’t have to prove the opposite. This anchors what PSD2 intended: refund first unless the bank can show fraud or gross negligence by the customer.

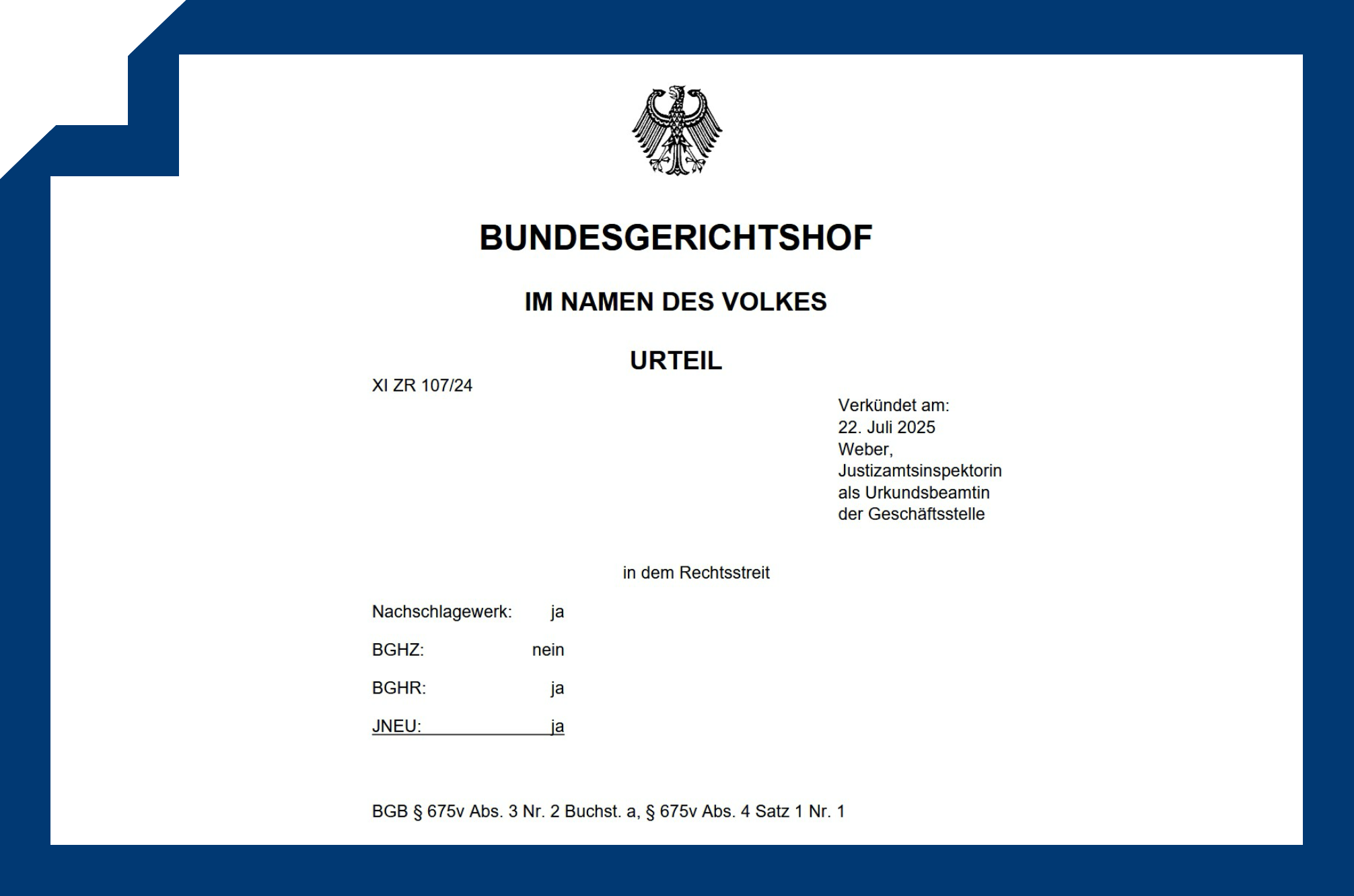

BGH, 22 July 2025 – XI ZR 107/24

Handing out TANs over the phone for a supposed “security update” was on the facts — the customer had time to reflect and continued. Result: the bank could offset the (found legitimate) refund claim under § 675v(3) BGB. Important nuance from the reasoning: not every TAN disclosure is automatically gross negligence; context matters (e.g., “momentary lapse” vs. extended conduct). Use this carefully: banks will cite it; you should focus on the factual threshold and the BGH’s warnings against blanket assumptions.

Conclusion from these judgements:

Together, these rulings confirm a two-step: (1) Bank proves authorisation/SCA; (2) only then can it try to shift loss by proving customer gross negligence. If either part fails, refund under § 675u BGB stands.

Banks argue “you gave TANs to a third party ⇒ gross negligence ⇒ no refund.” But Don’t let them generalize. The BGH did not say “TAN disclosure = gross negligence per se.” It stressed a case-by-case assessment and a high factual threshold before shifting loss to the customer.

So our advice is as follows, based on the above decisions.

Make the bank prove exactly what happened: timeline, screens shown at authorisation (amount/IBAN), wording of warnings, number of prompts, device binding steps.

Highlight deception context: caller ID spoofing, pressure scripts (“security update”), real-time coaching, look-alike domains.

Expose UI/SCA weaknesses: same-device pushTAN, unclear or late warnings, confusing labels (e.g., “confirm to cancel”), easy limit changes.

Stress intent mismatch: you never intended that payment to that payee for that amount → not “authorised” under § 675j BGB.

argue with a momentary lapse.

Further important decisions for this topic are as follows:

2) Appellate courts (OLG): where the law gets applied to real attacks

OLG Dresden, 5 June 2025 – 8 U 1482/24: Breakthrough on shared fault: even if a customer acted grossly negligent, a bank can carry contributory responsibility where its login or SCA design fell short (e.g., weak login; reliance on same device for PIN + pushTAN; poor warnings). The Sparkasse had to reimburse part of the loss (≈20%). For victims, this is a door-opener: argue bank-side failures in SCA/login design and warnings as Mitverschulden.

OLG Frankfurt, 6 December 2023 – 3 U 3/23

No liability where the customer ignored clear warnings and approved pushTAN/limit changes after a phishing contact; court found gross negligence. Banks cite this frequently; victims must counter with UI clarity, call-ID spoofing, deceptive task framing (“confirm to cancel”), and warning quality & timing.

3) Some (rare) first-instance wins for victims

LG Köln, 8 January 2024 – 22 O 43/23

Call-ID spoofing case: bank had to reimburse ~€10k–€14k after criminals provisioned a digital card (e.g., Apple Pay) via misleading pushTAN prompts. Court found no gross negligence due to deceptive UI/wording and spoofed bank number. (Use this whenever your bank tries to trivialise phone spoofing and UI ambiguity).

LG Wuppertal, 15 August 2024 (reported)

Victim recovered ~€39,000 after a near-identical pushTAN activation SMS arrived from the bank minutes before the phishing SMS — confusion the bank created. Good precedent for bank-induced confusion and message timing risks. (Official reporting via press/consumer outlets.)

What this means for your case (practical angles that work)

Stick to the PSD2 structure: demand immediate refund under § 675u BGB; put the burden of proof for authorisation/SCA squarely on the bank (BGH 2024).

Attack “gross negligence” as a high bar: emphasise call-ID spoofing, credible bank-like scripts, UI copy that mislabels approvals (e.g., “register card” / “cancel payment”), rushed real-time calls, and poor warning design. (LG Köln; parts of BGH 2025 nuance.)

Argue bank-side fault (Mitverschulden): weak login paths, same-device pushTAN, and lack of real “strong” authentication can shift part of the loss back to the bank (OLG Dresden).

Screen evidence matters: what exactly did the app/SMS show at authorisation (amount/IBAN/warnings)? Courts look hard at the last screen the victim saw (OLG Bremen/Frankfurt lines)

5) Why Finanztip’s checklist still helps

Quick starter: Finanztip’s practical checklist “Was tun bei Phishing?” remains a useful first-aid guide for victims. We recommend it as a step-by-step playbook right after an incident.

Avoid being revictimized

Victims should not accept “you were grossly negligent” as an automatic veto. Push the bank on its proof obligations and its own security design. Escalate with written PSD2 arguments, cite the BGH 2024 burden-of-proof ruling, and where applicable invoke OLG Dresden on bank co-fault when login/SCA is weak.