The EBA’s May 2024 report confirms there is no legal definition of “virtual IBANs” (vIBANs) in EU law. What many PSPs sell as vIBANs are IBAN-formatted identifiers that route to a separate “master account”. This architecture creates reconciliation benefits for merchants, but also a long list of AML/CFT, prudential, and consumer-protection risks — from KYCC (Know Your Customer’s Customers) blind spots to DGS (Deposit Guarantee Scheme) confusion and regulatory arbitrage across Member States.

What is a “virtual IBAN” — and what it is not?

No legal definition (yet). The EBA stresses that EU law contains no definition of vIBANs and that National Competent Authorities and industry lack a common understanding.

Operational reality. A vIBAN is an IBAN-formatted identifier linked to a separate “master account”. The master account has its own IBAN; the vIBAN is an alias that credits/debits are ultimately posted to on the master account. Depending on the use case, the master account may be in the name of the end-user or another entity (often a PSP) that allocates vIBANs to end-users. Incoming payments to a vIBAN are credited to the master account; some models also use vIBANs for outgoing payments from that master account. (see Section 2.1, pp. 6–7)

Typical uses. PSPs issue vIBANs to: (i) their own customers; (ii) customers of a partner PSP; (iii) non-EU customers via an EU partner; and (iv) corporates for group treasury/centralised reconciliation. (pp. 8–11)

Why businesses like them (the limited upsides)

Market participants told the EBA vIBANs simplify reconciliation, facilitate centralised payments and can reduce the complexity and costs of managing many sub-accounts. Some also pitch them as a workaround to “IBAN discrimination” (payers refusing a non-domestic IBAN) — but the EBA is clear that IBAN discrimination is already unlawful under SEPA and should not justify vIBAN proliferation (pp. 10–11)

The core risks the EBA flags (and why they matter to victims & regulators)

Unlevel playing field / arbitrage across NCAs. Divergent interpretations of the SEPA Regulation and ISO 13616 (IBAN standard) mean Member States treat vIBANs differently — enabling regulatory arbitrage and inconsistent supervision (pp. 12–14, 19–21).

AML/CFT visibility gaps (“KYCC problem”). When a PSP allocates vIBANs but the master account is held by another PSP, the “offering” PSP may have limited visibility of the actual end-users’ transactions and controls. This impairs transaction monitoring, due diligence and name-screening quality — especially in cross-border set-ups (pp. 15–17).

Funds Transfer Regulation friction. Under Regulation (EU) 2023/1113 (FTR), payer information is required at account level; in vIBAN chains where the end-user is not the account holder, fields can be misleading or incomplete — a risk FATF has noticed as well (p. 16–17).

FIU reporting fragmentation. NCAs and FIUs apply different views on which FIU should receive a suspicious-transaction report when master account and vIBAN sit in different countries/country codes; this creates gaps and delays (pp. 17–19

PSD2 qualification & consumer rights. If the end-user is not the master account holder, it is unclear whether the end-user has a “payment account” as defined in PSD2 Art 4(12) — knocking on to SCA rights, transparency and even fraud-reporting templates under the EBA Guidelines (pp. 21–23).

Instant Payments “Verification of Payee” pitfalls. Name-match checks can mislead when the vIBAN names do not reflect the master account holder; a payer thinks they’re paying X while the master account is Y (pp. 23–24).

Unauthorised activity risk. vIBAN chains can be misused by non-EU financial institutions or EU non-PSPs to provide payment services in the EU without the required authorisation (pp. 24–25).

CRD/branching uncertainty for banks. Some credit institutions issue vIBANs bearing a host-country code without a full branch there; NCAs diverge on when such activity constitutes a “branch” under CRD — another arbitrage vector (pp. 25–26)

Consumer-protection & DGS confusion. Users and payers often cannot tell who holds the master account, which NCA to complain to, and whether DGS protection applies (especially when EMIs are involved). Poor disclosures may mislead depositors and even complicate DGS pay-outs (pp. 26–28).

Red-flag indicators (Annex 1 — for AML teams and victims alike)

Risk is higher when, for example: there’s no direct contractual relationship with the master-account PSP; multiple PSPs split responsibilities; the master account is outside the EU; the offering PSP is not an obliged entity under AMLD; limits on transparency/transaction types exist; or the master-account PSP restricts information sharing about end-users (pp. 29–30).

Who is pushing virtual IBANs today? (non-exhaustive PSP map)

Below are PSPs (and banks) that publicly market vIBANs/virtual accounts or operate them behind the scenes. Labels differ (“virtual accounts”, “virtual IBANs”, “multi-currency IBAN”), but the function is broadly the EBA model above.

° Banking Circle’s vIBAN footprint

Banking Circle is arguably the largest issuer in Europe’s vIBAN stack. In 2022, the bank stated it had “over 13 million Virtual IBAN accounts” issued to institutional clients.

On its current product page it claims “29 million IBANs issued” across its virtual-account infrastructure.

In a 2025 LinkedIn update, Banking Circle further claimed “37 million virtual IBANs (vIBANs)” issued.

Crucially, the bank also notes it provides (virtual) IBANs to its clients who then assign them to their own customers—a layered model that squarely raises the EBA’s KYCC and supervisory-fragmentation concerns.

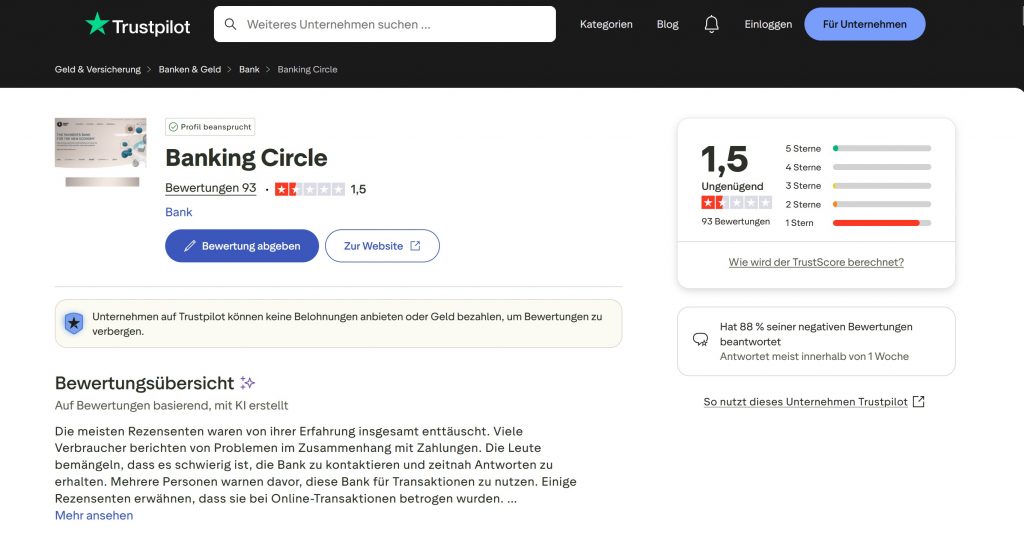

Reviews on TrustPilot for Banking Circle confirm EBA's concerns:

Trustpilot entries are unverified user accounts and reflect allegations, not adjudicated facts; the small sample and selection bias limit representativeness. Still, the themes mirror EBA concerns on vIBAN misuse and consumer-protection gaps

What reviewers report most:

Fraud/Scam allegations: Many say IBANs at “Banking Circle (German branch)” were used in Kleinanzeigen scams, fake “Finanzamt/GEZ” invoices, or invoice-redirect schemes.

Payments not received / chargeback frustration: Payers claim funds were sent to a Banking Circle IBAN but the intended recipient didn’t receive goods or refunds.

Support & contact issues: Frequent complaints about difficulty reaching the bank or getting timely responses once a transfer is disputed.

Role confusion (B2B bank / vIBAN stacks): Several reviewers appear not to be Banking Circle customers but payers to accounts held there; some explicitly mention “virtual IBANs.”

Company replies exist (“Unternehmen hat geantwortet”), but reviewers often say the response did not resolve the recovery.

° Other known vIBAN providers are

ClearBank (UK bank). Describes a virtual IBAN structure alongside “real accounts”, and publishes guidance on vIBANs and their uses.

MANGOPAY (EMI). Offers dedicated virtual IBANs tied to user wallets; docs also cover Verification-of-Payee flows for vIBAN pay-ins.

Currencycloud (Visa company, EMI). Spark provides a multi-currency IBAN solution with a single IBAN receiving many currencies; support docs set out how it works.

Modulr (EMI). Provides local IBAN options and unique account numbers for UK/EEA; regulated as an EMI in the Netherlands

Nium (EMI). Operates virtual account numbers and, via Banking Circle, issues virtual IBANs for funding accounts in EEA/UK.

Monneo (aggregator/PSP). Markets itself as a virtual IBAN provider for e-commerce merchants, integrating multiple banks.

Ebury (fintech). Offers named currency accounts with IBAN details for collections — functionally similar to vIBAN set-ups in some client journeys.

Note: “Virtual account” ≠ “virtual IBAN” in every case (some virtual accounts are internal only). Always verify whether external pay-ins/outs are permitted and who is the legal master-account holder — the crux of AML and DGS risk

The Bottom Line for Fraud Fighter

vIBAN stacks can anonymise the true counterparty from both the payer and sometimes the receiving PSP. That is a classic KYCC trap. The EBA’s own Annex reads like a red-flags checklist for exactly the cases we see in online fraud and “recovery” scams routed through layered PSPs. Until Brussels closes the definition gap and mandates transparency on the master account holder, vIBANs will remain a high-risk conveyor belt hiding in plain sight.

EFRI's take - what should be fixed (fast)

Define vIBANs in law. Clarify at Level-1 how SEPA and ISO 13616 apply to vIBANs; codify that a vIBAN is an alias of a distinct master account — not an account held “in the name of” the end-user by default.

Mandate KYCC transparency. Where PSP-A allocates vIBANs and PSP-B holds the master account, require reciprocal visibility (KYC data, screening hits, monitoring alerts) and unambiguous FIU-reporting responsibilities.

Consumer disclosures. Standardise a short-form notice on who the account-holder is, which NCA supervises, and DGS coverage (or not). Include a public “vIBAN-to-master-account holder” look-up for enforcement.

For explanation: The statutory Deposit Guarantee Scheme (DGS; €100,000 per depositor, per bank) protects only deposits held with credit institutions and only the legal account holder. In many vIBAN set-ups, the end user is not the holder of the “master account” — the account holder is often an EMI/PI (e-money/payment institution). In such cases, the DGS does not apply; instead only the safeguarding regime (trust/segregated client account) applies, which does not provide an automatic, guaranteed payout like a DGS. It is precisely this risk of confusion that the EBA highlights as a consumer-protection and supervisory concern.